The “Youth” Doctors

By Nada Skerly

Bucharest, Romania

Clarena/Montreux, Switzerland

September, 1971

If you can promise man youth, fortune and glory are yours. The world’s rich and famous will flock to you and pay you homage (and many dollars). And the sensation-hungry international press will help you advertise.

Preferable prerequisites are a gimmick (a mysterious-looking vial of “rare” liquid will do and a medical degree (for the comforting aura of legitimacy). Also important are a clinic (with impressive, gadget-filled “research” laboratory), and personal allure and credibility.

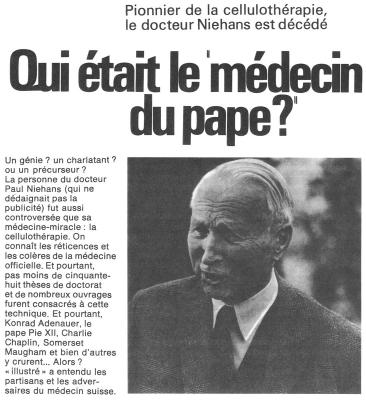

A man who possessed all these in good measure, and was the best known, most fascinating and controversial “youth” doctor, died this month in Burier, Switzerland. Even the selective Time magazine granted him a Milestones mention. It read:

Died. Dr. Paul Niehans, 88, the Swiss surgeon who won both reputation and fortune by trying to lead his celebrity patients to the fountain of youth; in Montreux, Switzerland. In 1931 Niehans developed his so-called “cellular therapy,” in which particles of lamb embryos were injected into the patient; he claimed that the treatment would retard the aging process, and cure almost everything from homosexuality to heart disease. Though viewed with suspicion by many fellow doctors, Niehans counted among his grateful patients Pope Pius XII and Gloria Swanson.

A Swiss physician continues to challenge the mystique. In an article appearing below the Tribune de Genève obituary of September 5, Dr. Pierre Rentchnick, Geneva cancer specialist, charged that Niehans had parlayed one apparently successful thyroid-cell injection some 40 years ago into a super cure for everything including cancer.

Niehans, he wrote, “never wanted to recognize that these cells are destroyed by the receiver organ, a phenomenon of rejection well known by the public since the popularization of organ transplants.

“He also pretended,” continued Rentchnick, “that his treatment permitted rejuvenation. This pretension, impossible to prove, captivated an international society, which doesn’t accept aging.

Niehans, said the writer, refused to discuss scientific problems and referred queries to a research foundation made up of a cult of loyal followers, mostly German doctors. (Niehans reportedly was related to the late Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany.)

Rentchnick also impugned the Papal “cure,” and said it was ultimately a Rome surgeon who healed what turned out to be a stomach hernia.

"If on occasion,” the writer concluded, “his treatments gave certain results…Dr. Niehans had the nerve to make of it all a doctrine insupportable by the most elementary scientific facts.”

In the well-appointed library of his Geneva office, the youthful Rentchnick muttered the word “charlatan” repeatedly. “Niehans had the fascination of a charlatan,” he reiterated. “The public is not scientific or rational. It wants miracles. And only he would announce that he could make them.

“Everyone wants to be young and active sexually. Why not? Patients would insist on going to him, then return asking, ‘Doctor, don’t I look younger?’”

His brown eyes narrowed with displeasure. “What could I say? I don’t know how to prove someone is younger. All their declarations were subjective. That’s not scientific proof.”

Rentchnick spoke of unsanitary treatment methods. The live animal cells cannot be subject to sterilization or they would die. “There have been many serious infections and allergies,” he noted. “And a dearth of preliminary examinations. But you don’t hear of the accidents. The patient, for one, is loath to admit he sought a rejuvenation cure in the first place.

“Cancer specialists telephoned me from the U.S.,” continued the physician. “What did I think of Niehans? Some patients came anyway, because if official medicine could not help, maybe this would. They will try anything.”

As editor of the Swiss medical weekly, Médecine et Hygiène, Rentschnik has researched the Niehans phenomenon for over a decade. Invited to an international conclave of cellular cultists in Paris in 1961, he described the attendees as “merchants.” Feigning ignorance about the effectiveness of the therapy, he got a colleague to comment, “But doctor, it brings in more money than general medicine.”

So it does. At the 26-bed Niehans institution, Clinique Générale La Prairie, located at Clarens/Montreux on the shores of Lake Geneva, a shot of live animal cells costs 128 dollars; a series of 10, 1200 dollars. Room and board adds another 450 dollars for the six-day cure.

Niehans boasted having given over 50,000 shots. By simple arithmetic, he was a multi-millionaire. In nearby Burier, a white, Renaissance-style palace, crammed with priceless antiques and paintings, attests to his commercial success. Patient tributes include two bejeweled hilts from King Ibn Saud of Saudia Arabia and the Imam of Yemen.

The practice of live cellular therapy is limited, according to Niehans clinic heirs, to one or two doctors in Germany. Few scientists can afford to be shepherds.

Niehans had a 35-acre pasture in the cheese country of Gruyere. There he raised a special flock of 500 black sheep, then slaughtered one or two pregnant ewes each week for the treatments.

An actual visit to the clinic is the proof of the pudding – if one might so grossly describe the nauseous process of preparing bloody clumps of lamb foetus for the injections.

From without, the two-story building of La Prairie looks like a cozy Victorian-period inn. Next door, one notes with amusement is a private girls’ boarding school. The school is marked on the local tourist map. The clinic is not.

From within, the dark corridors, closed doors and absence of people suggest the eerie secrecy of a Dr. Frankenstein movie.

It’s a Thursday, the frenetic, weekly injection day. At 4 a.m., a technician left by special van for the 36mile trip to the sheep farm. The five-week pregnant animal was transported to the nearby slaughterhouse at Villeneuve. (One of the Niehans “Ten Commandments” for cellular therapy specified that the clinic be located near butchery.)

After a blood check for disease, the animal was killed and the foetus ripped out by Cesarean section. The embryo was rushed to the clinic in a bag along with other organs of the mother. Time is critical for the cells, which have a six-hour life span.

Within an hour, six attendants had separated the organs into about four dozen categories, then cut, macerated and sieved them.

The blobs were suspended in a saline solution, then distributed among hundreds of 20-cc syringes labeled with patient’s names. At 8 a.m., Dr. Walter Michel, clinic director for the last 12 years, raced around to inject expectant posteriors.

Niehans’s hypothesis was simple if not scientific. His 160-page Guide to Cell Therapy reads like a cookbook: A dash of thalamus for this and a pinch of pancreas for that. He credited ancients for his recipes:

• In 1400 B.C., the Hindu physician Susrata prescribed eating genital glands of young tigers to cure impotence;

• Homer said Achilles ate bone marrow of lions for courage and strength;

• Alexis Carrel kept chicken tissue alive in a test tube by adding lymph cells of the rabbit, rat and horse.

His favorite was Paracelsus who proclaimed, “Heart heals heart, kidneys heal kidneys, similia similibus curantur.”

Post injection, Niehans said, cells scoot to the appropriate organs and replace underdeveloped, defective or aged counterparts. He termed the process a “modified organ transplant…a wonderful discovery…an unexplainable mystery of nature.”

He promised results within 14 weeks, only if the patient had abstained from liquor, smoking, sunbathing, sauna, Turkish baths, hairdryers, strenuous sports, medications and hormones. All could damage the “tender, new” cells.

Niehans claimed to cure anything from acne, heart trouble, diabetes, and cancer, to brain defects and personality problems such as bad temper, inferiority complex and homosexuality. Excluded were viral and infectious diseases.

The moneymaker however was the youth cure, which reportedly also wiped out “migraine, depressions, overwork and executive diseases.” He postulated, “Since the heart is tired after having beaten so long, why not refurbish it, strengthen it, with cells of the cardiac muscle…[and] placenta to activate blood circulation.”

Business fell off for a while because of specious cancer statements and a fine levied by the Swiss medical society of Vaud. “This bad time ended well,” Niehans later wrote, “as I was called in 1954 to Pope Pius XII and able to cure him.”

Niehans was denied the academic recognition he longed for. Only the church gave him a platform. As a member of the Papal Academy of Science, he stated in 1966: “In all modesty, may I give notice that I am near to the solution of the cancer problem.”

He theorized: Black sheep rarely contract cancer; therefore their cells transferred to humans would provide cancer immunity.

His “scientific proof” consisted of a poll of former menopause patients. There was a discrepancy in claims as well. In one journal, he cited 300 cases observed over two years; in another of the same year, the figure jumped to 3,000 over 20 years.

Dr. Michel dismissed the cancer issue by saying, “We take no advanced cases and treat only those persons who fear it and need a psychological reinforcement.”

Michel was withdrawn and defensive during the interview. Hard, small, brown eyes peered mistrustfully out of the gaunt, aged face framed with gray side-burns.

“Have you read the Rentchnick article?” he asked. “Did you hear him on television? It’s all wrong, all untrue.”

STOP, September 11, 1971

Then, in a torrent of French, he ranted about empirical medicine, treatment of causes and not symptoms and discovery of the smallpox vaccine.

“What is it you want, madame,” he repeated as nervous fingers played on the intercom buttons. “Look at these,” he demanded as he pushed forward a pile of magazines and newspapers.

STOP, the Italian tabloid, announced, “The blue angel (Marlene Dietrich) has a secret to remain eternally young.” How often does Dietrich come, I wondered. Niehans had warned against repeated treatment else “the human cells become lazy and atrophy.” (Dr. Bernard Bovet, the second clinic physician, later confided, “she gets facelifts.”)

ILLUSTRÉ, September 9, 1971

The Swiss pictorial, Illustré said Niehans admitted he loved risk more than science. It also listed Chaplin as a patient.

“But don’t mention Chaplin,” Michel quickly corrected. “He was never a patient.” Adenauer? A pregnant pause, then, “Er, we went to him,” said Michel.

He relaxed a bit as with schoolboy pride he proffered a Niehans obituary in the Gazette de Lausanne that he himself had written. “Do you know it?” he asked. “Very important paper.”

The secretary brought in a pile of Niehans texts in German, French and English, and all written in the third person. They were free for the taking.

A manifesto for “More sex Past 50,” or “Love and live longer,” cost 10 dollars; a cell therapy textbook, 26 dollars.

Michel decided to give me the former. (“You are lucky!” exclaimed Bovet later.) lt is the story of the clinic seen through the eyes of a former patient, a television performer and author. He is so convinced of the physical and financial value that he wants to open a Niehans affiliate in Jamaica. There, 200 million potential U.S. customers, “deprived” of the injections by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, could be treated with dried or lyophilized animal cells. These are also produced at the Clarens clinic under the trade name of “Cellorgan.”

They cost one-tenth of the live cell price. But, according to Bovet, give only one-tenth the effect.

The American Medical Association made a stand on the therapy during its 1968 conference on quackery. It’s report concluded, “If today’s Americans cannot find the quacks they want in the U.S., they will go halfway around the world for them…In Switzerland, Prof. Paul Niehans attracts wealthy Americans and Europeans alike…with his ‘cellular therapy.’ He carefully selects patients who are likely to respond to his treatment, which includes rest, good care and good food and excludes liquor and tobacco. That is enough to insure that many will feel better.

“But there is no scientific evidence,” it adds, “that his cellular therapy treatment has any value…and of course any injection of foreign protein could cause a bad reaction.”

What will happen to the clinic now, one wonders. The death of Niehans, of uremia, has left a void. The showman is gone. He held it all together with a personal conviction of invincibility and a roster of jet setters who were patients as well as friends.

Even detractors like Rentchnick concede to his charisma. A former patient’s first impression was of “A charming, handsome aristocrat, a man with a ready warm smile, simple and likeable. A man who inspired immediate confidence with a gift to make you feel as if you had known him for a long time, as if you were doing him a favor coming to visit him.”

That feeling is absent now. Maybe the institute needs a little rejuvenation treatment. The resident physicians are both 71 and look it despite having taken the “cure.” Dr. Bovet functions as English interpreter, a job he took about a decade ago upon return from South Africa. Unfriendly vacant blue eyes surveyed me guardedly.

Flanked by the tall, hunched over Michel and the heavy-set Bovet, for a cursory visit of the empty operating and examining rooms, I had the fantasy of being in the lair of medieval alchemists.

We proceeded down the dark, soundless corridor and saw no one. Patients were resting securely in their anonymity. Only the license plates on automobiles parked outside (Great Britain, Switzerland, Germany), gave a clue to the nationality of the current crop of clients. It is said that no passport is required and Niehans had personally handled all correspondence.

Michel excused himself to catch a train. Bovet left alone talked candidly and dispassionately about his work. “The job’s better than just sitting around,” he said. “And it saves the bother of making house calls.”

Without Niehans, there is nothing to sustain the myth. The youth fountain has run dry. And physicians continue to ask, “If this cure is so miraculous, why aren’t doctors all over the world using it? Unethical doctors could make a lot of money out of it; ethical doctors could win fame through it.”

* * *

In another corner of Europe, in the fascinating Byzantine and Latin metropolis of Bucharest, another “youth” doctor holds court.

Dr. Ana Aslan is known as the uncrowned queen of Romania. In an unlikely scenario for a Communist state, she is the pampered and subsidized darling of the government, a grande dame whose every whim is granted.

It’s not because her elixir keeps the leadership young and vital, but a simple matter of economics. Mme. Aslan is a major hard currency producer for this underdeveloped East European country.

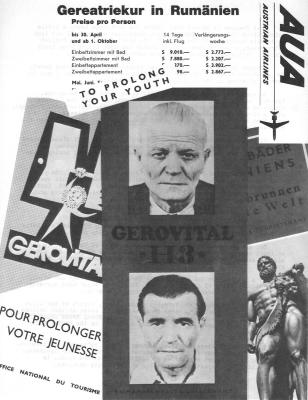

According to Imeco Export-Import in Bucharest, export of the Aslan rejuvenator, “Gerovital H3”, reaps an annual six to seven million dollars (one million from Switzerland alone). By international trade standards, the sum may appear modest. For Romania, dominated by the Soviet bloc it is a lot.

Mme. Aslan bolsters the local economy as well by “importing” foreigners under the category of “patient-tourist.” A massive state apparatus, involving the Romanian ministries of health, tourism and trade, is responsible for international marketing and publicity services.

The advertisement in the International Herald Tribune reads:

“Details” include multilingual brochures, which eulogize: “One of man’s most ardent desires, to prolong his life and fight the aging process, is realizable today.”

All you need for the Bucharest miracle, via Vienna for example, are two weeks and approximately 400 dollars (flights, hotel and injections inclusive).

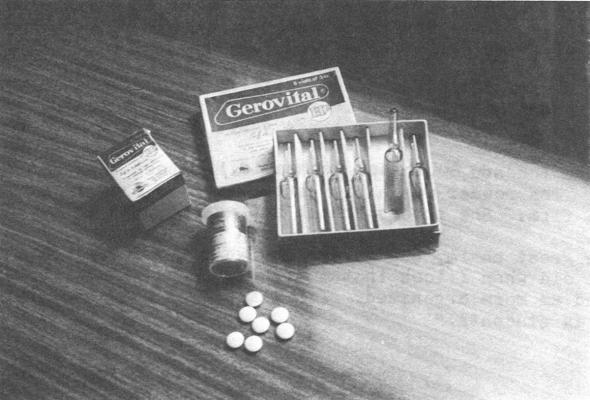

What is this mysterious concoction, which only Aslan claims to have? Gerovital is a colorless liquid, sealed in amber-hued glass ampules. It is also manufactured in shiny, white tablet form. Allegedly, it can heal heart and brain disorders, rheumatism, arteriosclerosis, depression, skin problems, and turn gray hair back into its original tint. Aslan also insists patients are less cancer prone.

The basis of Gerovital is procaine, also known as Novocain, a garden-variety anesthetic used by dentists to deaden the tooth nerve. An American doctor familiar with the drug (and the lady) said it also contains huge doses of vitamins E and B12. “She simply took two well-known factors,” he said, “a painkiller, and vitamins required by everyone over 40, and combined them. It has merit. But,” he warned, “she has propagated it so completely that she herself believes it is a cure-all.”

Although U.S. physicians promote vitamin usage. The effect of such enormous amounts has not been scientifically proven. Therefore, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration prohibits its import. It is sold in about 14 other countries on various continents.

At the Bucharest Drug Factory, where it is fabricated, Aslan personally analyzes each batch and final packaging bears her imprinted signature.

Since 1951, she has reigned over the Bucharest Geriatrics Institute. There she maintains a home for the aged (all Gerovital patients); clinics for outpatient and inpatient treatment, and a research laboratory complete with rat cages.

The first person I saw outside the three-story, white building was a shriveled up old lady. I shuddered a bit and wondered: patient? cleaning woman? unsuccessful case?

Inside, minding the shop while Aslan vacationed in Rome, was her associate and major domo, Dr. Cornel David.

Balding, 58, mild-mannered and ingratiating, David greeted me with a hand kiss (very Romanian) and a scrapbook of Aslan cures. There is no problem of anonymity here.

Subsequently he paraded old dolls, inmates of the home for the aged. For the last 20 years, they have earned their keep by being part of a pitiful sideshow.

Three of them stood in the corridor outside the conference room where foreigners are received. Bathed, outfitted and shaved or roughed, they waited sullenly for the summons.

The first act was Honorina Muller, 80, one-time arthritic cripple, in frilly dress, socks and sandals and silly grimace. A bright ribbon encircled her white hair. Upon cue she paced quickly the length of the room, back and forth, back and forth. “Look at the éclat of her eyes,” said David, excitedly shifting from German to French. “She has taken Gerovital since 1952.”

Next came Nicolae Toma, right side paralyzed with a stroke from 1947 to 1952. “Well,” said David, warming up to a little guessing game. “How old is he?” I looked at the lined face and shot back “Eighty-eight.” “Er, exactly,” sputtered David.

Like a marionette, Roma bent stiffly at the waist several times. Then, as though guided by an invisible thread, he raised and lowered his right arm. “Healed after three years of treatment,” beamed David.

Aurora Ionescu, 80, former asthmatic, has been institutionalized for 24 years. The powder was a bit caked, but the face intelligent and the handshake firm. She tutors French and was allowed to speak.

With great charm, she said, “Oh, what is 80 but four times 20. I only feel old when I look in the mirror. I have more energy than at age 45 and am more organized. I am happy. I head the library here and have my students.”

And with that, she pulled her white shawl around her yellow tailored dress, stood up and waited poised at the door for dismissal.

It was well rehearsed. In the corridor the following day, Mrs. Ionescu waited to participate in yet another demonstration. This time, it was for a group of prospective importers from the Philippines. The smile was gone and her gray eyes stared vacantly through the window toward the rose garden two stories below.

“Hello, Mrs. Ionescu. Do you remember me? We spoke together yesterday morning.” She looked up with narrowed eyes, then said guardedly, “Yes, what is it you want of me? Why do you wish to talk to me?” It was the sad reaction of someone who is constantly at beck and call.

The testimonials themselves were not convincing. One wondered how long and how well these individuals would have survived without Gerovital.

But one in pain doesn’t bother about scientific answers and seeks only possible relief. “Let them do to me what they did to Ruth,” said 59-year-old Esther Newill, a travel consultant from San Francisco. Apparently her American friend had had a successful experience.

Mrs. Newill, vivacious brown eyes sparkling through outsize eyeglass frames, talked of her around-the world business trip and the Gerovital stopover in Bucharest. “So far,” she said, pointing to her right hip, “I’ve had two days of shots and then more pain. But we’ll see what happens.

Mrs. Aurora Ionescu in her bedroom.

Nicolae Toma, a portrait from the Gerovital sales brochure.

“I know this is offbeat,” she added. “And my doctor told me that he would be the first to give me something new if he thought it would work. But he told me frankly he couldn’t help me any more, wished me luck and said to let him know if it works.”

Mrs. Newill had selected the cheapest of the two-week geriatric package tours – as inpatient at the institute itself. The initial examination cost 56 dollars and room and board plus injections another 12.50 per day. Accommodations are drab and depressing, but the center of town is a five-minute taxi ride away. She played patient in the morning and tourist in the afternoon, feasting on beautiful icons in the many mosques, rich folk art and Paris-copied boulevards and parks.

Some prefer to stay at a downtown hotel (21 dollars a day), then trek daily to the institute clinic.

The choice cure spot is the former princely summer castle of Buftea, located 12 miles from the city center. This lovely, 25-room retreat, tucked into a park, was built in 1864. Until recently, it was a hotel for Communist Party VIPs; also the setting for a Jean Paul Belmondo film. It boasts a private lake, mini mosque, outdoor bowling alley, and, now, a geriatrician schooled in tourism.

The ministry of tourism operates it as a Gerovital spa along with another at Etorie-Nord on the Black Sea. It plans to open the chateau of Snagov, 24 miles outside Bucharest, next year.

Dr. Trajan Oancea, head of the Buftea “clinic”, relishes his double job and talked animatedly about suppers under the stars, concerts and folk dance evenings.

The castle, still outfitted with the original antiques and plush furniture, can house 16 patients at prices varying from 18 to 35 dollars a day. At this visit, all but one bored math professor from Kuwait, were from Italy.

“We came,” said the wife of a middle-aged Milan industrialist, “because it was written up in one of our magazines and we were curious.” Her husband, jaunty in a suede green Romanian mountaineer’s hat, accompanied us on our walk around the lake. He waved at a young girl in hot pants, winked mischievously, and added, “It’s a good place to relax and we’ve got five more days to go.”

“Three-fourths of them come for sexual rejuvenation,” said Kamla Daswani, a beautiful young woman from India, confined to a bed in Otopeni. This sanitarium near Bucharest was originally built for Communist Party officials. A year ago, the ministry of health turned it into yet another Gerovital moneymaker.

It’s an ugly, one-story building with red-carpeted corridors the length of a football field reinforcing the impersonal atmosphere.

Behind the countless doors, at this count, were patients from Belgium, Italy, Germany and Austria-plus Mrs. Daswani – at an average charge of 25 dollars a day.

Mrs. Daswani had seven weeks to arrive at her conclusions. Shortly after arrival from Ghana, for treatment of rheumatism of the knees, she caught pneumonia and was forced to stay on longer.

“They have been very kind,” she said, wincing as she tried to shift her legs under the covers, “but I could tell you plenty about what goes on here.

‘Try Romania,’ my friends suggested and so I did. But I didn’t know it was such a lure for the impotent. Because I would lie here day after day, the guests would come by to see me and begin to talk about themselves. Also about others – what intrigue!

“They would say,” continued the winsome lady, ‘0h, Kamla, I feel much better. Don’t I look better?’

“It’s all psychological,” explained Mrs. Daswani. “How could they become younger in a few days? Or expect their hair to turn black? They give you a high protein diet and make you rest, but there can’t be a miracle,” she sighed dejectedly, as if for a moment thinking of her own health hopes.

(“It helps some,” remarked the American physician later, “but not everyone. Each of us is different and responds differently.”)

An aide entered Mrs. Daswani’s room. “Well, I guess they want me to rest now,” she said. Then she added with a smile, “Keep your fingers crossed. I hope to be out of here and on a plane for London tomorrow.”

Patients are encouraged to buy enough Gerovital to continue treatment at home. Purchased in Romania, a year’s supply of tablets costs a mere 1.70 dollars (compared to 60 dollars in Germany); the ampules, 204 dollars. There is also a face cream and hair-restorer.

Dr. David said there is no age limit to use, but recommended one begin at 45 for maximal prophylactic benefits and carry on for life. Reportedly one person in 5,000 is allergic to it and there are no side effects.

Every institute employee has tried it for ailments varying from despondency to lumbago. I began to wonder who was “Gerovital-young” versus chronologically young.

Dr. Alexandru Ciuca, a physician, and head of the institute’s sociological research section, was the only one objective enough to say, “Gerovital is not a universal cure-all.” He is also one of few who has successfully challenged Aslan’s sovereignty.

“Les girls” sunning at the Bucharest Geriatrics Institute.

The issue, which ultimately went to Party boss Nicolae Ceausescu for arbitration, dealt with planning for the country’s aged.

Aslan is preoccupied with her foreign cash-customers and indigenous gentry. The poor Romanian peasant pensioner would be the last to gain entry into the inner sanctum, and few of his Bucharest counterparts have even heard of the institute. Her solution was to let ’em eat Gerovital-mass distribution of the drug.

Ciuca objected to the exclusively biophysical approach. “Economics and social factors,” he said, “are as important as medical ones.” He campaigns for better housing (including communal farms where the rural aged can maintain their life styles), adequate pensions, and the establishment of social and hobby centers.

Apropos Gerovital, Ciuca said an extensive four-year test on 45year-old factory workers showed excellent results in combating early cases of rheumatism plus fatigue and nervousness. He shook his head impatiently as he added, “We should not overplay gimmicks and exploit the masses for cancer and aging cures. We need to know the cause of aging before we can talk of cures.”

Some months ago, Dr. Nathan Shock, of the National Institutes of Health in Baltimore and top U.S. gerontologist, curtly dismissed Aslan’s treatment as “unproven.”

In Rome, Dr. Marcello Perez, geriatrician, called it “a vogue” akin to the virility waters ballyhooed in Yugoslavia a few years back. He knew, however, three “fashionable” Rome physicians “who make a lot of money on it. They’re against official acceptance of the drug,” he added, “because they want to keep the charge high.

“But patients claim,” he said, “that they feel happier, and it eliminates some symptoms of aging.”

The storm of criticism may swirl about her, but Mme. Aslan preens majestically on the edge of her bed in the Hotel Excelsior in Rome and proudly talks about her favorite subject: Herself.

Still looking fit at 74, she can do as she pleases; go anywhere she wishes, while others, in security tight Romania wait six years for a passport – or forever.

Beady, megalomanial, own eyes peer out of a smooth-skin face edged with Gerovital-brown hair.

Her pale peach-and-white silk print dress blends with her colorless personality, but clashes tastelessly with the patterned black hose on her legs.

A gold bracelet and large, gold Peruvian sun god are souvenirs of trips abroad. There have been eight big ones so far, including one this year to the land of the midnight sun.

Curiously unaware of or indifferent to the impression she was making, Aslan bragged about having one of the most beautiful villas in Bucharest. “I do my own interior decorating,” she added.

Dr. Ana Aslan

“I am constantly being invited by the embassies,” Asland continued, “but I also entertain at home. My cook does everything, but I plan the menu, set the table and arrange the flowers.”

She paused, as would a schoolgirl waiting for approbation. “I have a couturier, but I help design my clothes. I also paint. If I had the time,” she added, in a flat, unemotional voice, “I would like to write my autobiography and some novels. People say I write well.

“I am kept busy,” she said. “An Italian film company spent a lot of time with me for a film on ‘The Best Known Women in the World.’ Loretta King and Mrs. Ghandi are in it and some Russian woman. I don’t know the others.

“Does anything annoy me? Yes. Dumb questions like why I did not marry. The man I wanted,” she continued unabashed, “wanted a rich woman. And he got her,” she added with smug finality.

Throughout, Aslan spoke French and maintained her Pekinese-like pout. “I have always been interested in extraordinary things. At age 16, I wanted to be a pilot. Then I became interested in anatomy and the extraordinary machine of the human heart and became a cardiologist.”

She spoke, of course, about Gerovital, and a new and more powerful offspring to be christened “Aslavital.”

How long did she think she could prolong her life? “My mother lived to 83,” she said. “I think I may live to 90. I have a horror of death. It is an injustice I must work against.”

Aslan and Niehans – so different yet so similar in many ways: Strong personalities, single mindedness, private or government subsidies, courtiers and spiritual heirs, and personal wealth and fame. They shared as well the grandeur complex, which excludes the possibility of making a mistake or being wrong.

“And they exist,” concluded Dr. Rentchnick, “because they are also supported by the public.”

Received in New York on September 21, 1971.

©1971 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.