The Aged In Singapore: Veneration Collides With The 20th Century

By Nada Skerly

Singapore

December, 1971

If you have the feeling Big Sister up there is watching you, she is. She also has her eye on the Pheng family and recently signified her approval to granddaughter Swee Lan’s marriage. Last week, everyone turned out for her birthday party. And, in general, Mme. Pheng Kum Sing is in the forefront of all family festivities and decisions.

Symbolically, of course. The grand old lady died five years ago.

Nevertheless, she is venerated – and saluted daily with burning joss sticks and red candles – in a manner few elsewhere enjoy while living.

The house is a simple, atap-thatched roof hut in a Chinese kompong or squatter’s settlement seven miles from downtown Singapore. Fire is an ever-present danger and rain filters regularly through the flimsy, patched wall. Four family members sleep in a small room on a railed, oriental-style, four-poster bed.

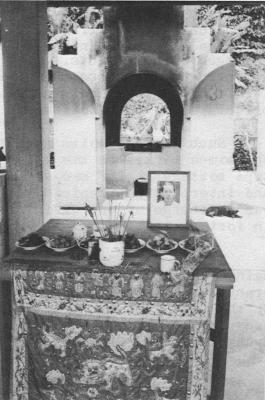

Grandma enjoys a niche of her own near the family altar – a bracketed wall shelf, which greets you at eye level as you enter the main door. There, beside a clutter of’ incense sticks, candles and prayer scrolls, her framed image reigns in solitary stateliness. At her left is a plaque of immediate ascendants and the god of good fortune. In the center stands the house deity.

On his birthday, hers, and for other important anniversaries, the mother of the house proffers six kinds of food: Fish, rice, noodles, buns, sweetmeats and tealeaves. (Men consider religion woman’s work and the wife is expected to mourn for her husband’s fore bearers as well as her own.)

To gauge whether the altar dwellers have finished “eating,” two coins are tossed to the ground. Tails up means “no;” head and tail, “wait;” and heads, “yes.” By such perfunctory convention, mates, jobs and judgments are also cast.

It’s all part of ancestor worship. A dutiful son is expected to care for his parents in this life and in the next. Neglect at either end or both is tantamount to parricide.

Michael Wong, a former Buddhist monk turned Methodist minister, explains, “This linkage of family ties is buried inside of us and we can’t get rid of it. If you break the law of filial piety, if you don’t respect elders and ancestors, you are punished by childlessness. Your ‘familyness’ stops there, and in the afterlife, you become a tientang, or hungry devil.” (During the seventh moon of’ the Chinese calendar, such orphaned souls are said to roam the earth in search of food and must be appeased by offerings.)

An elaborate funeral is important proof of filial piety. It also insures a proper send-off via the burning of fake currency so one will have spen6inE money in heaven. Clan funeral societies cater the affair and also supply mourners. In fact, one is fined if he doesn’t attend a fellow member’s wake.

The older the deceased, the more ornate the obsequies and the louder the wailing and keening. Advanced age is such a virtue that two years are tacked onto a woman’s age at death, and three to a man’ s.

The bizarre drama is open to any passerby daily in the death houses of downtown Sago Lane. One can wander in and out of the row of barn-like funeral parlors at will.

SAGO LANE DEATH HOUSE:

In the corner, a female corpse (identified by the blue embroidered funeral dress) has been laid out on a raised, wooden plank. Behind, streamers and a paper crown on a stick “hold the soul.” The priest chants to the accompaniment of cymbals and a bell as relatives wail and burn mock money in the square container. On the floor, odd-numbered offerings of’ rice and rice wine, oranges, buns and chop-sticks “re piled around a photo of the deceased.

Inches away, a caretaker is dressing another body in as many layers of clothing as the family can afford. (The rich may have 51; this poor man, wearing the plain blue robe designated for males, has only a white shirt and black pants.)

Near the entrance, mourners favor card games and Seven-Up while waiting.

SAGO LANE:

Mourners wear burlap and white cloth vests and head coverings. Left, a band tuning up to lead the funeral procession.

Alongside the death houses or funeral parlors, shops sell necessary accessories including wreaths and coffins.

Numerous stores sell intricate paper replicas of temporal goods like the miniature auto and ship at left. There are also mock houses, clothes, furnishings, cooking utensils, foods and treasure chests. These and millions of dollars in play money are burned in the temple incinerator at the right. Then it is believed they accompany the departed soul.

SANGHA TEMPLE:

Outdoor crematorium where final eulogies are made.

Interior of special warehouse where ashes may be stored in large yellow urns at a cost of 700 dollars.

By chance, I also visited a little known Buddhist temple and crematorium on the outskirts of’ the city. The original quest, according to my guide at this point, a 19-year-old self-proclaimed spiritualist, was for aged opium addicts. They were there all right, scrawny, bent, onetime rickshaw drivers and coolies. Now they tend the furnaces in exchange for food, shelter and a smoke. The drug is, of course, illegal and the priests allow them to indulge only at night.

Such large temples tend to give refuge to the elderly. In this one, the women worked in the kitchen and garden and lived in small, summer-camp-type cottages. The men were entrusted with selling scrolls and candles and interpreting auspicious dates from the bulky Chinese calendar. One was in charge of the divining blocks – kidney-shaped pieces of wood used in fortune telling.

Supplicants come for miraculous cures as well. Gifted priests, called saints by the brotherhood, are said to possess healing powers. They practice a form of “laying on of hands,” as the

\Christians recognize it. Or they may give the afflicted pieces of yellow paper stained with their own blood. These are to be ignited before the house god and the ashes drunk in tea.

Acupuncture is practiced and the use of herb potions widespread. Gen sing, a rare root and purported sex stimulant is the most prized and costly restorative, and Tiger Balm the best advertised. The originator of the latter amassed the world’s largest collection of jade sculpture with the profits.

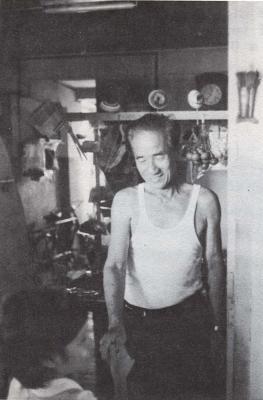

Sng Ung Nung, 71, a polygamist and professed Catholic, claims his murky well water is regenerative. He says aged customers began living on the premises 18 years ago and today number 140. The predominantly Buddhist institution, complete with three altars, became the Dragon Lotus Temple home. Also a tourist attraction after local newspapers denounced living conditions there as “Singapore’s form of euthanasia.”

The publicity brought in the Presbyterian mission and donations to replace the animal-pen lean-tos. But despite public condemnation, Sng remains the manager. He doesn’t even pretend to know patients’ names let alone their ailments. Cataract-clouded eyes peered at me mistrustingly. The feeling was mutual.

I learned inadvertently that the nicest structure on the rural plot is his private dwelling. It houses wife number one, a concubine and 20 children. (Actually, the marital arrangement is not uncommon here and a septuagenarian holds the record with seven wives. They are considered a status symbol. “Like getting a new car in the U.S.,” says one wag.)

There has been a spate of’ nursing home exposés in the last year. As a result, students of social work at the University of Singapore are aware of the elderly as a needy group and combine studies with surveys. (The elderly number only five per cent of’ the population and other words tend to be invisible in the social fabric.)

Center, Sng showing off “miracle” well water with patients.

Scenes from Yew Tee home for the aged.

The only government concern, students learn, are old beggars considered eyesores, a blemish and “menace to Singapore’s Economic Policy of Tourism.”

Some are put into the few state-run homes for the aged, but only if they are without kin. Many are. ‘The current elderly population is predominantly made up of Chinese immigrants who poured into the area in the 1930s. They worked at the most menial trades and a large number labored in the tin mines of what is now Malaysia. Malaria and rheumatism, from mining knee-deep in water, claimed a many of them. Those who survived were usually alone. Either they had left families behind in China or never married. As old men, in the absence of a normal family unit to revere and coddle them, they turned to government or religious institutions for asylum.

Clans sponsored some of the residences, as did individual entrepreneurs. A timber magnate owns the Yew Tee home in an isolated corner of Singapore. (A few miles is a great distance in a country only 14 miles wide and 26 miles long.) Except for the string of Chinese lanterns, incense burners and scampering monkeys, it resembles a U.S.-style turkey farm. Long, open-side sheds house patients. The overseer, a former health department official, ministers alone to 130 persons. The aged have to fend for themselves and the stronger ones help to feed and dress the weak and bedfast. The government dispenses free medicine once a month.

About 70 per cent of the patients are lone immigrants and male, and subsidized by the government or clan insurance benefit societies. The remainder, according to the manager, have been abandoned by their families.

Singapore also has a disproportionate number of immigrant spinsters. Most famous among them are the Chinese amahs who came as indentured servants and became highly proficient and respected housekeepers and nannies. Called “black-and-white amahs,” because of their white tunics and black, billowy trousers, they would loyally serve a family for decades.

Old age was, of course, something else. But to prepare for it, the ladies devised an ingenious institution called the kongi, a kind of amah sorority house. They rented rooms above a shop where they could spend their days off and later live permanently in retirement. They pledged to remain single, and to contribute regularly to the support of aged members.

The kongis are dying out and lack fresh reinforcements. Amah-ship doesn’t appeal to the young Straits-born Chinese, as indigenous Singaporeans are called. They opt for factory or bar jobs – and marriage.

Finding an old-time kongi and its fabled members was a fascinating adventure. A Cantonese-born, multilingual sleuth and I spent a rainy afternoon poking around old tailor and curio shops. It could have been a sequence out of a Charlie Chan movie.

The hunt finally narrowed to 40 Dhoby Chaut Street and a fish and aquarium supply store. Surely a dead-end. Then, as if by magic password, the inscrutable old woman who stood there ushered us into the inner sanctum.

Amah look out,

Miss Lam.

In a small room big enough for a table, two chairs, a radio and a small Catholic wall shrine, Chow Ah Goh, 70, offered us orange soda pop. But little conversation until she could allay her suspicions. (She turned out to be the amah lookout.)

Eight retired amahs and 11 working ones occupy what turned out to be a small two-room flat. The room, downstairs was jammed with utensils and food cabinets and a pool-table size dining table. Reluctantly, Miss Chow and her cohort Lam Ah Chan, 69, led us up a shaky, stepladder stairway to the loft bedroom. (I wondered how the ladies, both wobbly with rheumatism, could maneuver them.)’The 12-by-14-foot chamber had a bed, a window, and a peephole cut through green linoleum to the fish store below. Near the entrance was another small altar with paper lilies and portraits of Mary and Jesus.

Carefully stacked against every available inch of wall space were dozens of frayed suitcases, trunks, paper-wrapped bundles and cartons. There were Diamond Fruit and Heinz Malt Vinegar boxes, over 100 containers protecting keepsakes and possessions of the sisterhood.

The women get some help from welfare, of course from “the girls,” and some rice and oatmeal from a nearby Catholic church. Other words their lives seemed circumscribed by the four walls and their own reticence. It was surprising then when Miss Lam decided to share some of her treasures.

From a cigar box she pulled out an inexpensive bead rosary, a faded baby snapshot of a goddaughter living in her native Canton, and a photo of two boys (sons of her last employer). There were also three likenesses of herself. I later learned that everyone keeps photos up-to-date for funerary purposes; also to give as a gesture of friendship. I was touched when she offered me one.

Miss Lam’s only adornment were pale, green jade earrings, the size of brass tacks. They are believed to purify the soul and favored by many elderly Chinese women.

For good measure, Wang Yeow Cheng, 75, wears a jade bangle as well. She says it protects her against nasty falls. Mme. Wang came from the Chinese port of Swatow for a holiday in 1937 and got trapped by the war. She, too, wears the amah-type trouser garb, but there the similarity ends. She is one of the imperious breed of w men some irreverently call “The Dragon Lady:” the tyrannical Chinese mother-in-law.

In pre-war China, they ruled the household, controlled the money and bossed around sons, daughter-in-laws and concubines. In Singapore, conservatives like Mme. Wang still try to exercise the art.

Daughter-in-law Daphne Wang rebelled after four years of sharing the same roof. She was Straits-born, educated in France and resented the chronic intrusions. “I couldn’t take it any more,” she says. “She demanded complete obedience as a sign of respect. It came to the point where if I wanted to make a dress, I would have to consult her on the pattern and material. If I wanted to go to the movie or visit parents, I needed her permission first.

“She still can’t get over the fact we moved out without asking her. She needs that power to feel successful in old age. She clings to the old tradition and doesn’t compromise. At my house she waits stiffly to be ceremoniously received and served.”

Those gestures mean, respect to Mme. Wang. With an acrimonious smile, she pronounces old age “disappointing. They let me down,” she says. “In the old days, one was consulted more. Daughter-in-laws were then ignorant. Now the young know better and the aged are pushed aside as ignorant.”

She evokes pity, for other words the woman is kindly and had a hard life. She raised two children alone on a meager income from lace making. Now, failing eyesight and a stubborn outlook make her depressed and bitter.

Goh Kok Kee somehow escaped becoming addicted to mother-in-law-itis. She swings with the times. Her 68-year-old tanned face is framed with short, waved hair. And it is hard to tell where the smile leaves off and the wrinkles begin. She’s barefoot and wears a frilly blouse and native sarong skirt. She’s a marked contrast to a portrait of herself as a 15-year-old bride. Only a small, somber face is visible from under a large crown attached to a rented, brocade tent with trapezoid panels.

TEA CEREMONY:

Daphne Wang kneels before her mother-in-law to offer a bowl of noodles (for long life) and two eggs (symbol of happy occasions). This is a birthday ritual performed with the phrase: “May your luck be as smooth as the Eastern Ocean and your life as eternal as the southern mountain.” Red packets, containing money, are also given.

KUSU FESTIVAL:

The aged in particular observe this annual pilgrimage to the island of Kusu, an hour’s boat ride from Singapore. Legend says Tua Pek Kong; the god of prosperity once performed a miracle here. The island itself is not much bigger than the temple and worshippers come with offerings of chicken, pink dyed eggs, fruits and flowers and pray for luck, health and prosperity.

Mme. Goh laughed at the quaint costume and jumped up to serve us some ginger beer. One had the comfortable feeling of being at home.

So apparently do others. All her children have stayed on: Four siblings and their mates and children for a total of 16 persons. They live in a circular, cantilever house with lattice windows, some architect’s dream of the 1930s.

It is their house and Mme. Goh endeavors to make it so. She rises early each day to do the food shopping and does all the cooking although there are servants to help. “One must work hard to keep the family together,” she says, her small, black eyes twinkling. “Many of my friends have been deserted by their children because they fail to think modern.” She spoke Hokein dialect, but the word “modern” in English Kept popping out during the conversation.

“She only interferes,” says daughter-in-law Pat, a bank officer, “to say we should use Chinese medicines. She believes in all those roots and herbs and wants the children to take them. But,” she adds, “she allows me to go my own way.”

The roles are reversed in the Koh household. The daughter-in-law, as the major wage earner, is boss and already threw her mother-in-law out. “Forget the myth of the submissive, shy Asian wallflower,” says Daphne. “This one wears the pants.”

The elder Mme Koh Chay Neo, 70, could do nothing to please the woman and was rebuffed at every turn. “In her insecurity,” says Daphne, a foster daughter, “she lowered her dignity too much. She even polished the shoes and served her meals. It should have been the other way around.

“One day, she appeared on my doorstep, suitcase in hand and crying. Of course I took her in, but after a month I sent her son an ultimatum: ‘She is your responsibility. But if you send her to an old age home, you must sign the paper. It will bear your name’.”

Under fear of losing face, he took his mother back.

She sleeps in a storage bin off the kitchen, in a room piled with boxes. The spacious salon and beautiful orchid garden are off limits when family or company are around.

The sarong is torn and her face has a bewildered look. Even her grandson ignores her except to criticize her English. Ironically, a Peanuts cartoon perched on the stereo speaker reads: “Dogs accept people for what they are.”

No one is home so Mme Koh bustled to serve us fresh coffee and peanut cookies – in the living room. Despite the sameness of her days, she talked animatedly about approaching 71. “There is to be a great party,” she says hopefully. “’They said I might get it.”

The Mme. Kohs are called “casualties of the jet age.” Observers say that under the impact of urbanization, westernization and education, traditional reverence for the aged is starting to give way to rejection.

Dr. Tan Eng Seong, a psychiatrist, says, “The ethos of veneration has become impractical. As a developing country, we look to the West for models and old values go by the board.

“Cultural values,” he continues, “say it is good to be old. Lau, meaning aged in Chinese, is a term of respect. But it is only an idiom of speech and very few who are old enjoy it. To be respected nowadays, you need a large bank balance to back you up.”

The government for its part is investing in youth. Eighty-six per cent of the population is under age 30. Much is spent on economic development, education and defense; little on social security or welfare.

Educators like Dr. Lau Wai Har lament the loss of “treasured values such as honesty and trust” because of the “growing materialistic outlook.”

Since breaking colonial ties with Great Britain in 1959 and leaving the Federation of Malaysia, Singapore has zoomed ahead to become an economic giant in the Far East second only to Japan. The mini city-state, only double the size of Manhattan and with a population of two million, attracts investors, traders, hotel builders and tourists. It offers something for every taste – from Peking duck and hamburgers to drinkable tap water and sweet corn ice cream. It is green and clean and likes to bill itself the Switzerland of Asia. (Litterbugs are fined 167 dollars for a cigarette butt.)

Singapore’s most impressive domestic achievement is its urbanization program. Under the motto of “One apartment every 36 minutes,” it has constructed one million low-rent units in just over a decade. In the process, it razed kompong hovels and resettled 600,000 persons into two satellite cities called Queenstown and Toa Payoh. One-room apartments rent for 10 dollars a month and outright ownership is possible at low cost. By 1960, the government plans to house half the population in modern dwellings.

In the process, it is anxious to amalgamate a society once separated into distinct ethnic groups: 75 pr cent Chinese, 14 Malay and 8 Indian.

Mme. Koh in her Sunday best.

In the new housing units, the three races plus Eurasians are forced to share each floor and suffer each other’s cultural peculiarities. The Chinese, in particular, are criticized for their noisiness. For them, it is a way of life. They are a gregarious folk and given to having numerous, festive, loud family parties. The only one silent is grandma’s spirit. And if it is not family, it is the radio blaring. There’s no way to shut them off because all the apartments have wire mesh transoms leading into the common corridor. It helps circulate air – and conversations.

Some American observers call the trauma of being uprooted from homogeneous kompongs Future Shock, after Alvin Toffler’s bestseller. The small apartments relieved many of the tyranny of grandma. There is no room for her. Nor for her nagging about, “Remember the name you bear. Do not forget to remember your ancestor. Cultivate his virtues. Do not cast a shadow on his merits and virtues.”

There is also no one to nurture traditions, which give meaning to life and provide some psychological buffer to being in strange, new surroundings. No one to nudge you about the positive aspects of what Rev. Wong calls "family ness.” He explains, “Familyness gives you a sense of Purpose. It gives you a sense of belonging in spite of daily meaninglessness.”

A Methodist minister who has resided in Singapore for 22 years also worries about the “overnight change.” In his Southern U.S. twang, the Rev. Gunnar Teilmann says, “They are attempting in less than 15 years a transition which took generations in America. Kompong life is like a Georgia plantation 150 years ago. In those days, there was room for everybody, even the mentally ill unless they were dangerous. Here in the high-rise, there is no room for the misfit, the unemployed or the aged.”

They were indeed not designed with the elderly in mind. Elevators, for one, stop only at every fourth floor. This, say social workers, creates a problem in releasing infirm aged from the hospital to the flats. Each building has a ping-pong table for the youngsters, but no lounge where the old could sit and visit. In the kompong, there is a community hall attached to the temple for this purpose. In the apartments, to give young couples occasional privacy, they sit forlornly on the building door stoop.

The building code plays havoc with certain religious practices. Those daily burning joss sticks make authorities nervous about blackened ceilings. One recent widow, thwarted from venerating her husband in the old-fashioned way, finally settled on a modern substitute. Each morning she tries to waft up prayers by fanning three electric light bulbs skyward.

It is also illegal to build bonfires to feed those roving devils during seventh moon observances. It ruins the grass around the new buildings and is called “destroying government property.” So kerosene cans are used instead.

The government, for its part, doesn’t envision the elderly as a priority group. “There is always another son or daughter to take care of them,” says a Housing and Development Board spokeswoman.

QUEENSTOWN:

Hayak and family.

Their Indian neighbor’ s door with Ganesh portrait (god of good fortune) and basil leaves.

Chinese doorway with scrolls and incense holders.

Typical apartment building with clothes drying on suspended sticks (resembling skewered meat ready for barbecue).

Touring Chinese opera visits the neighborhood.

“The population is basically young,” she adds, “and the aged are not a consideration nor a problem.”

The buildings are for people like Hayak Bin Sahith. Happiness for the 31-year-old Malay chauffeur is Apt. 127 G in Queenstown. It’s having a small, L-shaped room, indoor plumbing and a refrigerator for his wife and two infants. “It’s cleaner,” he boasts, the floor doesn’t get muddy when it rains as it did in the kompong and there are none of those terrible mosquitoes.”

The view from the one window, barred so the children don’t fall out, is another building. And the Chinese are loud. But Hayak is tolerant because he intends to learn. “It’s good to be mixed,” he says. “The Chinese know how to make money and to spend it on education. I want to know how, too. If I stick only with Malays, I am forced to criticize others. But that doesn’t help me to understand my mi6takes or to improve myself.”

Outside the building, he points with pride to nearby schools and sports center, the supermarket and swimming pool. To accessories of young adult life.

They mean nothing to his grandmother, a beautiful, stately lady of 80 found scouring pans on the dirt floor of the Lorong Jodoh kompong. Hers is another world, a page out of a textbook about denizens of a tropical jungle. Five minutes away from the paved highway and 20th century air-conditioned luxury hotels, one enters a densely vegetated area thick with mango, banana and coconut trees. One hears the chatter of birds and geese first. Then, in scattered patches among the sweet potato and tapioca gardens, one sees dwellings, and finally people.

MALAY KOMPUNG:

Mrs. Binti dishwashing;

Her daughter cooking at the mango tree.

“From my house to yours, I can see your face and that makes me feel free.”

The Bintis. “Why do you want to take our picture,” asks the husband. “Do you expect us to die?”

(Photos are considered funerary preparation.)

Hayak’s birthplace is aflutter with food preparations for a family party. His widowed mother, 53, is frying fish, a sister is peeling vegetables and even three-year-old Abdul is on the floor stirring some kind of cake batter. So nothing would burn, we interrupted only long enough to meet the elder Bintis and hear of their pilgrimage 13 years before. They are Moslems, as are most Malays, and the trip to Mecca was a heart’s wish granted by the children. There wasn’t much money, because all are laborers, but enough was saved for the three-month voyage and visit.

Mrs. Binti gazes proudly at her grandson in his uniform white shirt and black tie. He is still her boy and loyally comes home every weekend and contributes to expenses. And he is getting up in the world. But the apartment doesn’t impress her.

“I don’t like it,” she says through the translator. “You always have to close the door. From my house in the kompong to yours, I can see your face and that makes me feel free.

“I don’t feel comfortable there,” she adds. “It’s a strange place and I feel lost.” She points to the mango tree growing out of the middle of the kitchen. “I look at this tree,” She says, “and it makes me feel strong.”

Yee Lai, 68, and a Chinese, gathers his strength from family togetherness. Even though it means living in the concrete jungle of Toa Payoh. He and his wife have a one-room, floor-level apartment located near that of a son. Yee quickly explains they are not physically under one roof only because the units are too small.

He also finds it important to emphasize that his boys (another lives in the same community) provide all their meals. The wife brings the food when she returns from her babysitting routine with the grandchildren.

“They are dutiful sons,” he says with a proud smile. “Each gives me 20 dollars a month pocket money. I have no worries.”

The god of good fortune smiles down at the Yee from his perch on the bracketed wall shrine. There’s not room for much else in the apartment since Yee bought a candy stand with a part of his retirement pension. (As former steam boy at the one-time British naval base, he received 3,000 dollars in a lump sum through the provident fund. Normal retirement age is 55; 50 for civil servants.)

New jobs are impossible to find so Yee and others depend on their families. In his case, he earns a few extra pennies a clay from the candy and cigarette cart. He keeps it in the apartment because he lacks a vendor’s license. “The main thing,” he says, “is to keep busy.” He also enjoys the people and as a result was elected to the residents’ council.

His life is complete, explains the interpreter. “He’s happy because he has grandchildren (10 from the two sons and two daughters), and especially grandsons. That means the family line is assured.”

One Chinese maxim suggests, “Bear a son next year and later breed grandsons. Earn a lot of money and save a lot of money.”

Of course that is the kind of thing youth abhors hearing. It just isn’t modern and doesn’t jibe with what you learn at school. Besides, it may come from poorly educated or illiterate parents – who don’t even speak English.

Rev. Teilmann frets about the communications gap. Literacy rates have jumped to 90 per cent among the 35 and under age group. But in the thrust mama may, for instance, know only Cantonese and her child prefers to speak only English.

Education has also made youth impatient for independence, the antithesis of clan-oriented living. “You still see the veneration, the bowing and smiles,” says Teilmann, “but it is a shell. One that is breaking all to pieces in this struggle for freedom. They hate it inside. Some parents,” he adds, “are holding their children by love. But no longer by authority.”

He speaks from the vantage point of running a so-called “S.O.S” telephone service. The majority of callers, who spill out personal problems to a core of volunteers, are teenagers. And Chinese.

The overall problem is also basically Chinese. It is the change over from a “chopstick generation” to a “knife-and-fork generation.” From an aged society which holds tenaciously to traditions like ancestor worship – to something a little different. At one time filial piety held you responsible for the spiritual as well as physical care of your loved ones.

Except for isolated cases, there is no pattern of physical neglect here. (Despite the admiration for things American, Singaporeans don’t follow our lead of casting away the elderly.) What is happening, according to one psychiatrist, is “the start of spiritual neglect – and it is inevitable.”

It shocks and confuses the current aged generation because aged has been synonymous with deification for centuries. It’ll mean adjusting, and “thinking modern” along the lines of a Mme. Goh who distains old formalities.

Yea Lai and customer.

It might mean mixing a bit of the old with the new as symbolized in this photograph. The temple squats in the midst of a Toa Payoh housing complex because the law protects houses of worship. It alone remains of all the structures, which once constituted a Chinese kompong.

And it might work out despite the gloom of western-educated observers and their “Future Shock” prognosis of a dehumanized society. There are, in my opinion, too many Yong Wengs around for that to happen. On the surface, Weng gives the impression of being super Western. He likes the long haircut and the jeans and the “cool” sounds in music. But after he says the showy things, which establish him as contemporary, he allows the conversation to turn upon himself and his personal values.

He says, “I know I must look after my parents until the last days. I don’t know why. Even if I marry, my mother will live with me and it will be the duty of my wife to look after her. It’s not written anywhere, but that’s part of it.”

Received in New York on March 6, 1972.

©1972 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.