The Aged In India: Myth and Despotic Mother-In-Laws

By Nada Skerly

New Delhi, India December, 1971

It was King Yayati, according to Indian epic, who borrowed his son’s youth for 1,000 years, only to return it willingly. “What I have realized,” he said, “is that there is no end to desire. Gold, cattle, women and food you seek and attain, but the satisfaction each affords is short-lived since you lust for more and more of them. After a thousand years of enjoyment, the mind craves for further and fresh enjoyment.”

Children sit wide-eyed as the village storyteller continues the tale in the tone reserved for immortals.

“I want to end this phase of life and turn to God,” said Yayati. “I want to live without the duality in mind of victory and defeat, profit and loss, heat and cold, pleasant and unpleasant. These distinctions I shall eradicate from my mind, divest myself of all possessions, and live in the forests amidst nature, without fear or desire.”

And so he did. For 30 years, he subsisted on water – as gods are wont to do – and another on air alone. An inflated ego extended his earth penance several decades. But eventually he got to the retirement town in the heavens reserved for super beings.

Even today, Indians extract a moral from the myth for their own aged outlook. When a man sees his skin is wrinkled, hair is white and the sons of his sons – as the saying goes – then it is time to retreat from active life and make one’s peace with the gods.

Life styles, tradition and attitude help to ease the withdrawal. By comparison, pressures to remain productive and attractive increase as one ages in the U.S. One is propelled toward face-lifts, youthful fashions and flirtations in an anxious struggle against being put on the shelf.

If the Indian makes it to age 50, he can finally relax. (Twenty years ago, life expectancy was 32; now it is 52 for women and 53 for men. About five per cent of the population reaches age 55; only two per cent, 65, or over.) In fact, care of and respect toward the aged is the one stable factor in a country racked by differences.

There are 826 languages and dialects (14 of them official), diverse religions although 83.5 per cent of the people are Hindu, and a rigid caste system. Actually, to talk with an Indian, one must make all these qualifications and then also determine regional and cultural moorings.

But whether he is a Brahmin (the highest caste), or an untouchable, within his own home, the elderly individual is deified.

Mrs. Rajrani Taluja, 80, a widow and a Brahmin, lives with her son and grandchildren, plus several nieces and cousins in a spacious one-story house near the presidential palace in New Delhi. Sleeping rooms, in traditional Indian style, are located around an open courtyard. In the middle of it, on coffee table-shaped beds (used for sleeping in hot weather), wheat from the distant family farm is drying.

Each morning, Jagdish Chander Taluja, 50, discharges a small ritual before he leaves for work in a government office. He stands before his mother, bows stiffly from the waist and with outstretched arms reaches for her toes. After she blesses him, with a tap of her hand to his head or shoulder, he straightens up and fetches her morning tea. When he returns, he remains to chat for a while. After work and before bedtime, Jagdish repeats the ceremony. All family members also greet her with a low bow.

It is also a common sight on Delhi streets, especially man to man. A nephew, for instance, approaches his uncle and makes a quick one-arm salute to the older man’s right toes.

Jagdish estimates he spends at least three hours a day keeping his mother company. “Duty to parent comes first,” he says, “whether one is rich or poor.”

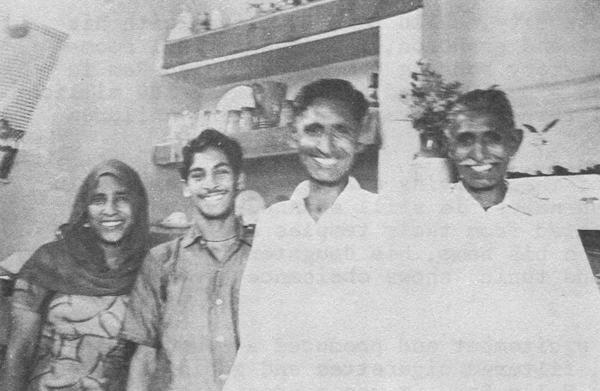

Bullu Ram;

Below, Mrs. Taluja

At the outer edge of the city, Bullu Ram, 60, lives with his oldest son, daughter-in-law, and grandson, 14, in one small room plus kitchen of an ugly two-story housing compound. Bullu Ram is an untouchable. He works as a sweeper and is one of the 100 million Indians whom Mahatma Ghandi tried to elevate by renaming Children of God.

Outside the confines of these living quarters, however, Bullu Ram (untouchables have no surnames) is still shunned by the upper classes. He is even segregated from their temples and must attend one of his own caste. But in his home, his daughter-in-law, a diminutive figure in trousers and tunic, shows obeisance by veiling her head in his presence.

Our visit caused much excitement and produced a round of cokes, chili-spiced rice krispies, filtered cigarettes and gaping neighbors rooted to the doorway. For Bullu Ram, it was a prestigious afternoon. He puffed contentedly on the black, cigar-like bidi, and spoke self-consciously about his four children and 15 grandchildren.

Although the retirement age is 58, menial trades have no cutoff date. Bullu Ram earns 10 dollars a month cleaning out state housing units. About two per cent of the salary is deducted for health insurance; another 10 per cent for the civil service provident fund (a retirement policy eventually paid off in a lump sum).

(Per capita income in India is 70 dollars a year; an unskilled laborer earns about 70 cents a day. That would barely feed one person; many more eat every third day. Delhi is called the “invisible city,” because most of the four million inhabitants are without housing. At night they sleep in the streets and at dawn the dark, sleeping forms resemble an invasion of locusts.)

Despite his small income, Bull Ram professes no worries. “I don’t know the price of food,” he says, “I don’t have to bother. My family takes complete care of me. After work, I come home and have my food and tea and bed. That is how they show their respect to me.”

His son is a telephone company electrician and handyman. Prize possessions in the nine-by-twelve room are a neon light and radio he put together himself plus a sewing machine. Beautifully embroidered cloths cover the one bed; the suitcases used for clothing storage, and the wall shelves holding glassware and bric-a-brac.

In a special corner of the kitchen reposes Bulla Ram’s one hobby – a hukka or water pipe. “It takes so long to get it started,” he grins, “but I prefer it to cigarettes in the evening. And then my neighbors come over and we smoke it and have tea.”

“What do we talk about? Oh. ‘how are you’, ‘I have a new grandson’ – things like that.”

So far, the two families visited could represent the norm anywhere of widowed parents staying with their children. For India, this is a new style of small or nuclear family. It is a by-product of industrialization, the gradual migration to larger cities, and a chronic housing shortage.

However, 80 per cent of the population still resides in the villages. And it pursues the tradition of the joint family – a commune with perhaps dozens of family members living (and sometimes quarreling) under one roof. As the sons marry, they bring their brides home, and, in the few wealthier houses, more bedrooms are added on. More likely, possessions are stored in a locked cupboard (one per family) and individuals sleep dormitory-fashion under the stars.

As head of the joint family, papa holds all the purse strings and makes all the decisions. Only he can determine who works the land or goes to school, and who may attend festivities. Whether on a farm or in a family-owned factory, each individual has a particular job, and finances are pooled and shared equally.

Inequalities are most likely suffered by new brides. If not humble or subservient enough (most start off making cow-dung patties used for fuel), the mother-in-law can become oppressive. The plot thickens if an embittered spinster sister decides to join forces.

Mama dictates what the girl wears and when, what she may purchase (including baby items), and when she may leave the house. The young husband may suggest an afternoon stroll, but mama can deny permission. If she is bored, she will demand the girl’s company for herself.

In Bombay, I met two married businessmen, aged 47 and 53. They live with their 75-year-old mother, a widow, who is still boss. If one wants to buy a new suit, mama decides first if there is enough money.

Naturally the system gives enormous power and security to the aged. It also solves the problem of the sick, disabled and widowed. There is a place for everyone. But it functions only if there are male heirs to build the family unit.

Girls don’t count. They are costly to marry off. And once they leave home, ties are broken and they belong to a new set of parents. If you are cursed with girl babies, you keep trying for a boy. Particularly since a son is essential for the funeral ceremony. It is he who cracks the dead parent’s skull so the spirit may escape the body.

Children are one’s old age insurance. One Indian calls them “lottery tickets” – the more one conceives, the better the return. Those who survive, till the soil as children, and tend the aged as adults.

This is the reason why family planning has an uphill fight in India. It is also a matter of virility. An employee who was persuaded while drunk to have a vasectomy cried to his superior that he would lose face in the village. They would wonder why the continuous pregnancies had stopped.

About 53,000 babies are born daily. By the year 2000, the population is expected to double to one billion. Cities like Bombay with 5.5 million are already babels of beggars and homeless urchins. Of families so poor they sleep under a cart or keep house in iron sewer pipes, which must reach 150 degrees under the merciless sun. And where do you put grandma?

As a grandpa, Mukand Sal Sachdeva, 68, thinks pensions are the answer. At least for “deserted parents” such as himself who have had only daughters and now no one to provide for them. In his case, money is hardly a problem. He owns two grocery stores which cater mainly to embassy-type whims for whiskies, canned butter and Iranian caviar. But he complains that taxes take 90 per cent of everything over 6,000 dollars.

We sat over lunch prepared by Mrs. Sachdeva, a handsome, tall, plump woman with smooth skin and gray hair. She wore a plain, white cotton sari and diamonds worth at least six carats on one finger and in her ear lobes.

Stainless-steel bowls clattered on the large, square wooden table, and I had my first lesson in eating with fingers. There were lentil and pumpkin curries and deep-fried pancakes to spoon them with. Also fried potatoes, rice pilaf, mango and lime chutneys, and yogurt. Most dishes were spiced with hot chilies, and when my eyes and nose began to water in reaction, Mrs. Sachdeva felt complimented on her cooking.

The house was large and empty, and still. Where four girls and their friends once scampered, there were now only wedding-portrait reminders. Sachdeva winced perceptibly as he recalled dowries, catered banquets for 1,000 guests, and sari presents for women in the groom’s family – all multiplied by four.

A rich bride anticipates a trousseau of some four dozen saris (gold brocade ones cost over 600 dollars each), and at least five diamond-pearl-ruby studded necklace and earring sets.

The dowry varies from 100 to 7,500 dollars. That represents a year’s wages for some – or a lifetime of debt. As a result, parents rarely accumulate savings and when aged are totally dependent on their offspring for support. If they should die before the obligation is repaid, the burden falls upon the oldest son. It is then his duty as well to provide dowries for any remaining unmarried sisters. Some are forced to hold down three jobs in order to pay all the bills, and often must postpone their own nuptials.

As new family head, he also has the burden of supporting lazy or less talented brothers and guiding them in a parent-child relationship. His wife becomes “mama” to sister-in-laws.

For the children, the big-family system provides a ready-made pool of babysitters and cousins to play with. Couples are carefree to leave for study or diplomatic service abroad, or extended holidays, because their children are cared for. Invariably, those free to travel are the primogenital and his wife.

Disadvantages of the system are obvious to westerners: It encourages parasites, discourages individual initiative and prolongs child-like dependency. As conductor Pierre Boulez once so aptly said, “You can still love your mother, but you must learn to feed yourself.” There is no privacy or solitude and the bickering, backbiting and jealousies are legend. The top wage earner has some clout, but a namby-pamby’s wife is subjected to so many indignities, she is a candidate for suicide.

Despite the vagaries of joint family living and its numerous detractors (mostly the young, educated), it continues to survive because old and young need each other. It provides social security against the outside world, one which begins just outside one’s village.

The venturesome find an immediate change in language, food and customs. It is easier to stay at home and let the family find you a job. For some with university degrees, that may take years. Since property and dowry are essential for a good marriage, one is again dependent on papa. Those who try to break out of the mold and rush into love marriages rather than those arranged by the family, fear disinheritance. Then one belongs nowhere. For an Indian, alone-ness is anathema.

The more money or property in a family, the more likely members stay together – even the would be mavericks.

Tucked in among the pink palaces of Jaipur, the Gobindram Ramchand family does a brisk business in jewels. It also owns a foundry, which turns out thousands of brass elephants, and camels for U.S. export.

Four sons run the business, but father Gobindram, 74, wearing a black pillbox cap and white dhoti, or maxi loincloth, still keeps the books. He also rules over six families squeezed boarding-house fashion into tiers of rooms above the main store. “Downstairs we make the decisions,” says eldest son, Ahuja. “But we always consult father on family matters such as the marriage of my son.”

Ahuja is about to become a grandfather, making four generations under one roof. But their affluence is not visible.

Rickety stairs lead up to dismal quarters. Each family is allotted two rooms, which are constantly padlocked. (You can tell if a woman is married in India by the ring of household keys tucked into her sari slip or tied to the veil corner.) The rooms barely accommodate a double bed and a wardrobe or two. Parents sleep in one, the children (up to five) in the other.

There is no community dining room or living room. The bathroom is a cubicle with a hole in the floor and a shower spout in the ceiling. In India, sinks are rare and bathtubs considered unclean.

Ahuja’s one concession to modernity was to construct separate closet-size kitchens for each family. He explains it was “to satisfy individual tastes and because women are the source of arguments and thus are left to themselves.”

The oldest part of the dwelling, where Ahuja was born, is empty except for a tangle of springs and mattresses. In the clearing of one room, however, a widow, 80, wearing white rags, sleeps on the floor. “She is alone, but considered a sister and can remain,” says Ahuja. The distinction is one of caste rather than bloodline.

At his beckoning, the new daughter-in-law, head appropriately covered, approaches with cokes. She touches his feet in esteem as do his sons and younger brothers. Particular deference, of course, goes to the patriarch, 74, and his wife. Mrs. Ramchand was draped in the common white garb of aged women, and sported seven one-fourth carat diamonds in each ear. Not so common. Gobindram turned vegetarian last year after his son died in a motorcycle accident. It is a sin,” he reasons, “to kill children of other animals.”

The son’s widow, 35, has been absorbed by the family along with her five children. “No, of course, she would not return to her parents,” says Ahuja. “If she did, her brother would not feel the same responsibility towards them that we do. My father pays for the children and the oldest son, 17, will be educated by the family and placed in the business. He is loved as part of our brother.”

Without being prodded, he adds, “It is unthinkable that she would remarry. She can serve only one God and, therefore, only one husband.”

The reverence toward males is instilled in a girl from childhood. She is taught to defer to her brothers and her father, later to her husband and in-laws.

Once a year on Karwa Chauth or Father’s Day, wives observe the occasion by fasting 16 hours and praying continuously for their husband’s health and longevity. Mahabil Chand, 60, a retired government economist, accepts the sacrifice as natural.

“She is economically dependent on me,” he says. “Her father schooled her until she was 12 and at 14 we were engaged, and then I took over the responsibility. So, of course she prays that I will continue to be able to look after her.”

A married son shares the newly built house in the fashionable residential area of Hauz Khas Enclosure in New Delhi. (Two daughters are students in Washington, D.C.) The family sat watching television, but a refrigerator positioned in the living room competed for my attention.

Chand’s son wore the traditional at-home outfit for males: Billowy, white cotton pajama bottoms with a matching over blouse. (The aged often complain that children affront them by wearing western pants and shirt in their presence.) The women wore the special red, green and gold brocade saris for this one celebration.

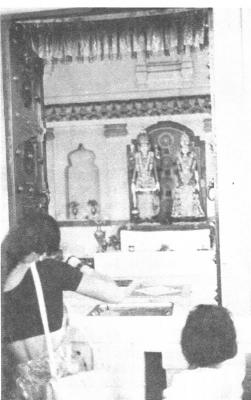

Around 10 p.m., the moon came out, signaling the time for prayer. The family altar, located in the corner of a guest room, resembles a small, old-fashioned gas lamp with one section cut out. Statues and pictures of the deities repose inside, behind burning sticks of jasmine incense.

The women knelt and symbolically offered stacks of flatbread and sweetmeats to the gods, then threw rice at them. Finally, they ascended to the flat rooftop to cast rice and water in the direction of the moon. That concluded the rite and the fast. It was time for dinner.

Sudha Arun, 28, of Bombay, deplores the deficiency of formal education, which has forced women into subservient roles. At best, she says, aged upper class women have learned the cultural arts of singing, dancing and playing the veena, a string instrument. Mrs. Arun, by contrast, is a graduate chemist; also the wife of a publisher and mother of two pre-schoolers.

Her in-laws live with them as does a divorced brother-in-law. Although brought up in a joint family of 48 persons, Mrs. Arun is critical of its viability in contemporary times. “My mother-in-law,” she says, “was 16 when she married and uneducated. She had to kowtow to her mother-in-law and now that she has her turn, she wants me to do the same. She is miffed when I don’t consult her on things.”

“Well,” she continues, “I have my own will and rationale. Why should I live her way? At her age, she had no other outlook or alternative.”

Mrs. Arun, chic in a modern-print beige sari and mod eyeglasses, beamed at the compliment on her contemporary living room decor. “I would prefer to have my own home,” she says, “to live alone with my husband and children, and decorate as I like. If I buy something, mother-in-law says, ‘You know we can’t afford it’. It’s the same with clothing. She buys it all.”

“Also I must cater to my father-in-law and be here for his one o’clock lunch.” (Only after he finishes, may she have hers, usually with the mother-in-law). “Fortunately she hasn’t balked at my going out with my husband. Others will say, ‘You know father needs someone to serve him his tea at four o’clock’.

Mrs. Arun said she couldn’t return to her job because the mother-in-law wanted to retire from household duties. So she spends the day directing a cook, two servants, chauffeuring the children to nursery school, cooking complex vegetarian dinners, and politely listening to the in-laws.

“I could have insisted on living apart,” she says, “But my in-laws hang so upon my husband. So I accepted them. I did it because I love my husband.”

“So do I,” says Anita Dhall, a swinging hostess in Madras, who wears both jeans and saris slung low on the hip. “But I had to get out after two years of living with my in-laws in Chandigarh. Do this, do that. I just couldn’t get used to it. Perhaps it’s because I had an English stepmother. There was no privacy. Another brother had to go through our bedroom to get to the bathroom. If we felt nasty, we simply locked him out.”

Mrs. Dhall and her husband are transplanted Punjabis. That is a cultural group from the north, and West Pakistan, which adapts well to foreign parts of India and elsewhere in the world. The southerners, in contrast, are more orthodox and conservative and frown upon western style dress and party giving.

The Dhalls enjoy their independent merrymaking, but observe certain family obligations. At least twice a year, they return to his family to spend their holidays. “I find,” says Mrs. Dhall, “that I love them more since we live apart.”

Raj Vig cannot accept the notion of the dis-jointed family and regrets its demise in the large cities. With almost stoic pride, she talked of their being “a duty with every right. If only the young would compromise a bit and learn some discipline,” she says. “But rich girls only want to play.”

Mrs. Vig, a matron of 45, with a son in graduate studies at Ohio University, has survived 25 years of mother-in-law-ism. She seems to feel it is good training. “My father was a widower and he worried about my happiness. So I would never, ever let on that I was the least bit disappointed,” she says smugly. She adds that she is now number one daughter-in-law – “which, after all, means something,” she adds proudly.

She does recommend that mother in laws prepare for their abdication. That they turn to hobbies for diversion rather than caged daughter-in-laws. Perhaps they could do charitable work for the poor, she says. But that concept is foreign to most Indian thinking.

“Hindus do not possess the social consciousness of westerners,” explains The Illustrated Weekly of India.” [They] have not built hospitals or schools. The devout might object: ‘Is not prayer enough? Can man do more than God?’

“When they see a neighbor suffer, their compassion is aroused, but they do nothing to mitigate his suffering. [They say] it is the fruit of karma.” [Karma translates retribution to expiate sins of a previous incarnation.]

“Is there any point in man interfering with the scheme of things?”

The Parsis say “yes.” They are a tiny religious minority of 105,000 centered in Bombay. They are Zoroastrians, originally from Iran, and provide for their own through a special fund. There are no beggars among Parsis, certainly a rarity among Indian communities. On any street, anywhere in the country, one is besieged by Memsib-muttering persons. Many are sponsored by a mendicant’s Mafia.

The Parsis limit the number of their offspring, educate them, and, in Bombay, own many of the businesses. Perhaps their most famous native son is Zubin Mehta, conductor of the Los Angeles Phil, harmonic.

The Bhardas welcoming Sam home.

Sam Bharda, 29 a mechanical draftsman, immigrated to Toronto. Mum (mother) Mehroo sat in her two-room, Bombay flat and shared his letters and wedding photos.

Over refreshments of orangeade, cookies and shelled walnuts, she says, “Of course I would like to have him here. But he has a better opportunity there.” Although a member of the so-called uneducated generation, Mrs. Bharda is open-minded and unselfish. Her neighbors describe her as a “giver” rather than a “taker.”

“Even if Sam remained in Bombay,” she adds, “I wouldn’t insist on his living with me. There isn’t that much room. Why should he be cramped?” Much to the delight of the Bhardas (the father is a retired physical education instructor), Sam and his Australian wife came home to await the birth of their first-born.

Since they left, money and letters come regularly. In the offing is a trip to Canada. “But we shall stay only one year – to see him settled,” says Mrs. Bharda. “I want to come back. I have a daughter and my home here.”

In other Parsi families, support of aged parents often falls to a daughter who marries late if at all. Coomi Damania, 32, earns 120 dollars a month as an executive secretary for an insurance company. That is a top wage in any bracket. Her salary helps to maintain three children and eight adults, including parents nearing 80. Two brothers also contribute to the family income.

The Damanias live in a neat but cramped two-room apartment in the Parsi section of Bombay. The area is easy to identify because streets and apartment hallways are kept clean. In their anxiety to be hospitable, the family offered a huge second breakfast of grilled fish, breads, cookies, fruit and tea. “It’s nothing much,” says Coomi. “If mother were here, she would fix you something lovely to eat.”

Mrs. Damania, 76, had a recent thrombosis and was under intensive care in a private Parsi hospital. The 24-hour electrocardiogram unit alone cost 53 dollars a day, or almost half a month’s salary. “It doesn’t matter,” says Coomi. “We’ll manage. For mother, nothing is too good.”

Others would have been piled into state hospitals to await a speedy death. There is no other type of repository for the ill aged except for a few orange-crate like structures where they are penned in squalor.

The Dalmanias took turns posting an around-the-clock vigil with their mother.

Father Jamshedji, 78, does his stint after work at the Burlington Social Club where he is a waiter. He owned one of the first taxis in Bombay and was active until a few years ago when his eyesight began to fail. When I congratulated him for having such good children, tears welled in his eyes and he nodded his head silently.

Back at the house, Najoo Damania had returned from her morning watch bearing me flowers. Despite the sadness and preoccupation with a sick loved one, she thought to make the touching gesture of welcome. The Damanias shower acquaintances and each with warmth and open affection unusual in India.

Boys do hold hands and men occasionally embrace, but there is no hugging within a family. Palms are joined together in greeting and farewell without much shade of emotion. T.K. Nair, a sociologist from Madras, says, “We’re not demonstrative. We provide food and care for one another, but the manifestation is different.”

For example, there is no communication between a father and daughter after she teaches 14. She is on her way out of his household. Mrs. K. Subramanian, a teacher, grew up in southern India. “I never touched my mother except when my father died,” she says. “There’s just no physical contact. Parents are sacred.”

In the south, one prostrates oneself before parents, elders, and in-laws. The wife walks behind her husband and never sits down across from him unless both are aged. She eats only after he finishes, usually cleaning up leftovers from his banana-leaf “plate.” She addresses him with the formal “you,” as she does her parents, and never uses his name to his face. It would be considered disrespectful.

Puzzled by the formality and absence of natural affections, I asked Prof. Nair what binds the family together. Why do children care for their elders?

“Because of fear and social pressure,” he replies. “All our lives we are told it is a sin to neglect aged parents. We may not want to have them live with us, but we have to, or something may happen to us in the next incarnation. It is something in us. It is also a guarantee that my son will care for me.”

“I have the fear although I am educated. I am not sure there is a future life, but anyway something bad may come to me. This dichotomy leads to great mental strain. To the public, I have to be secular. But I am not.”

“My parents,” he continues, “are 70 and 62, and live 500 miles south in Tiruvattar. My work is here in Madras. I should protect them and have them here with me. But they won’t come. Why not? Because my wife would run the house since I am the breadwinner. They couldn’t accept that.”

“People in the village are asking: ‘Why do you leave your parents?’ I feel bad and don’t know how to tackle the situation. A son must take care of his parents. If not, he either can’t afford to or is indifferent.”

FESTIVALS:

Goddess of victory;

Household decorations to celebrate “Victory over Evil”;

Burning of “Evil” monsters;

Temple sanctum.

“Then they start to harass my father and ask him if that is the thanks he gets for educating me. I know he feels isolated and doesn’t really accept our not being together. But he wants to be independent and stay on the land. What shall I do?”

As a partial solution, Nair sends money home. So does K. Subramanian, another southerner living in New Delhi. Village post offices keep a public scorecard on remittances and tattle on laggards.

“It is my obligation to send money,” says Subramanian. “In India, it is natural for parents to ask for help, and we are obliged to give it. If my mother says she will come to stay with me, I must accept her. It is in the scriptures, in my conscience and in my heart. And there are no strings attached.

“In the U.S., I noticed the elderly may suffer and be in want, but will neither ask nor be given.”

During Diwali, the major festival akin to our Christmas, there is much asking and giving. To celebrate the return of a beloved goddess from enforced exile, families light lamps, exchange gifts and sweets, and pop firecrackers.

For some firms, Diwali marks the beginning of the new accounting year and red ledgers are blessed with red powder, red, inverted swastikas and fresh basil leaves. The oldest and the youngest of the family lead the rituals.

During my brief sojourn in India, I also caught the festival of flowers, the 9-day celebration of good over evil, and the annual immersions of the goddesses of knowledge, fortune and war. At public functions, speeches began with: “Mr. President, gods, ladies and gentlemen.”

They were family events with the elderly in particular at the fore of each private and public ceremony. In general, there was much saluting of deities. I was impressed that the Hindus were so religious.

That is not the reason, a Hindu scholar told me. The masses have no entertainments and their only outlets are sex, births, weddings, funerals – and festivals. Thus ceremonies are long and elaborate.

“It is wrong to conclude the Hindus are religious people,” concurs The Illustrated Weekly of India. “They are more ignorant of their religious heritage than Christian, Muslims and Sikhs… Hinduism has grown like a vast forest [of scriptures] over centuries and one gets lost in it.”

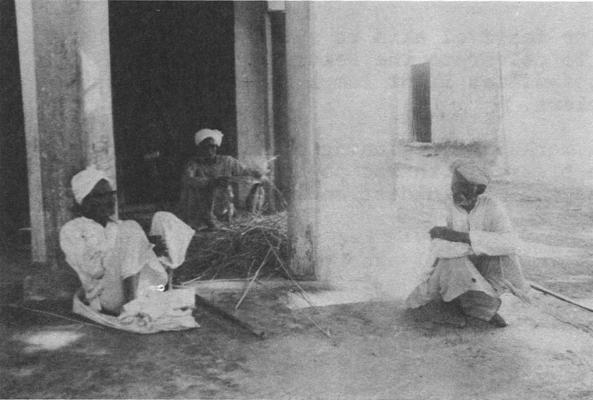

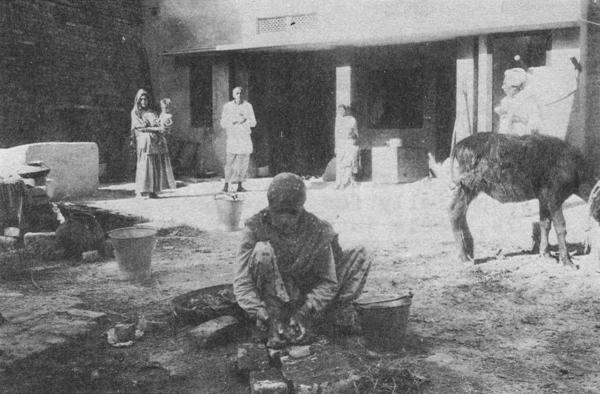

LIFE IN CHHITERA:

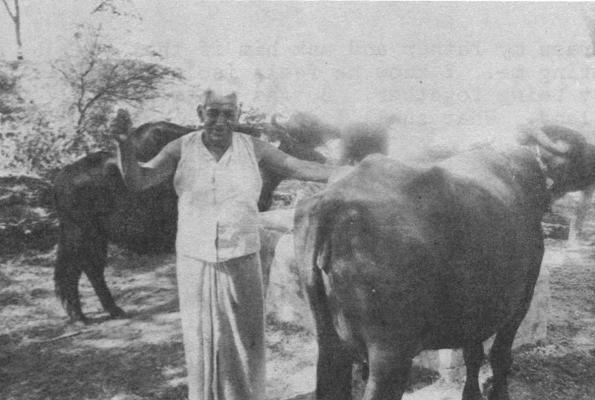

Singh and bulls

Untouchable grandmother and grandchild

Daughter-in-law making cow dung patties

Children carrying it

Old woman resting.

“Temple going is a social event…to make votive offerings to deities [about money and health problems]…“Hinduism embraces animism to monism and there is a deity for every wish… Festivals have no meaning beyond fun and feasting.”

In the absence of festivities, time sometimes hangs heavy – especially for the elderly. Sleep fills the gaps. Ratan Singh, 74, peels jute. “So I don’t think about the past,” he says.

Actually, Singh is better off than most. He is the richest landlord in Chhitera, a village 25 miles north of New Delhi. He is master of his house, wife and eight children. And rather vociferous on village matters.

For 30 years, he was principal of a school in West Pakistan. He retired to the family holdings in 1947. Since then, he has done nothing. He brags about being the first in the village of 1,100 to get an education. But he is indifferent to the illiteracy of the present generation. At an hour when youngsters in the U.S. are tackling homework, I saw children carrying heavy bowls of cow dung home from the fields.

Singh’s primarily interests are his bulls and 50 acres. “The village wanted to buy a tractor,” he says, “but I opposed it and threatened to sell all my land. I told them ‘I won’t be yours, and you won’t be mine’.”

He is an autocrat at home as well. Nothing is bought or sold without his approval, and he enjoys the respect of his brood. When hospitalized in New Delhi for several months recently, a grandson college student slept each night on the floor beside his bed.

Elsewhere in Chhitera, men sat or rested in groups and passed around the water pipe. Women picked through harvested rice and gossiped.

In Koliwada, a primitive fishing village north of Bombay, women repair nets and sell fish well into the years. There are no lone or lonely persons. The single and widowed are adopted by neighboring households.

During the drowsy, humid afternoon of my visit, villagers were dozing inside their thatched-roof huts or sitting under banana-leaf “awnings.” They chattered and giggled while searching each other’s hair for lice.

Although old and graying, there were handsome women wearing green-and-purple printed sarongs and literally pounds of gold body ornaments. The ankle and arm bangles, gold bead necklaces, and coral and gilt nose rings represent life savings.

Earrings of tooled gold were so heavy they tore holes in the earlobes.

The fishing folk were puzzled by the white-woman intruder, but offered two straight-backed chairs outside a hut for conversation. They giggled over my translator’s explanation and questions. But the word “American” prompted yet another introduction as Nixon, age two, appeared before me. His mother smiled shyly and said she liked the name.

Kennedy is also a household name in the nearby hamlet of Palmer. A weathered, color print of the late President hangs on the wall of a plantation-style veranda – next to family wedding portraits and a picture of Jesus.

For the Desilva family, the railed porch serves as a kind of open-air living room. For, inside the 14-room house, there are nothing but beds for the 64 occupants.

It was a sultry, tropical afternoon in a jungle area thick with banana trees. Most of the inhabitants were again asleep, including an old man sheathed in a loincloth and snoozing by the doorway.

Inside, Jabel Desilva, 84, awoke from her nap and talked about a “full life.” She had seen 24 grandchildren born and pointed out one of them, a schoolteacher home on vacation.

When asked to pose for a photograph, there was a slight delay. Then from somewhere in that dark, dingy house, she pulled out her treasure – a massive gold cross and neck chain. She struggled to fasten the clasp, then barefoot and in soiled sarong, she posed in her grandeur.

Dr. A.S. Najpal of Jaipur reminded me of the sophisticated Air India rajah symbol. He, too, wears a white Nehru tunic and full beard under a black and orange Sikh turban. At 58, he is the retired county health department director. During his tenure, he had sparked an extensive vaccination program. Now, he plans to devote remaining years to medical research.

J.F.K. & company.

The aged Hindu, to wit King Yayati, should occupy himself with prayer. Religion belongs to old age, says The Illustrated Weekly of India. It is part of the third and fourth stages of life. The first two are for studies and raising a family. Next, when old, one should retire and pray and meditate. Ultimately, one should renounce mate and all creature comforts in an effort to fully contemplate God.

There are six million sadhus or hermits who subsist in icy mountain caves. The study of yoga prepares them for their arduous existence. “Yoga,” says The Illustrated Weekly, “with its rigorous body and mental disciplines is beyond the capacity and understanding of common people.”

Adds a wag, “Asceticism is worthy, but impractical for most Indians. As it is, you can’t get mother-in-laws to give up those keys and retreat.”

Others joke about yoga and its swami teachers as “India’s major export business.” Jet-set pilgrims led by the Beatles and their Maharshi have tarnished the image of more serious seekers.

The Sivananda Ashram or yoga center at Rishikesh, in the Himalaya foothills, is an exception. It is dedicated to eradicating eye disease and helping lepers, as well as providing a spiritual refuge.

Americans come to meditate as do Indian aged, widows in particular. So-called “widow ashrams” provide sanctuary for these women, much as convents once did in the west. By tradition, Brahmin widows cannot remarry. They are taught to dedicate their lives to prayer and austere living. In that way, they can contribute to their husband’s spiritual welfare.

In one recent instance, an ashram became a convenient haven for an embarrassed, fired, government official. After being physically ejected from his private railway car, the deposed head of Indian railways announced he was retiring to an ashram.

It requires a hardy soul to do it. Two elderly women live at the Sivananda Ashram. After 18 years of sleeping on the dirty floor, and suffering bugs, stench, torrid heat and unpalatable food, one Hungarian woman was promoted to the orange robes of a swami. Another, a 63-year-old newcomer from South Africa, is wilting somewhat. She was told to make a three-month pilgrimage to the South. After traveling third class and depending on handouts, she returned with a high fever, but undaunted.

Rajvati Shivraj built a cottage at the ashram. in 1957. She says she felt a peace and contentment there that a city life with her wealthy sons no longer afforded.

“The third age,” she explains, “is bad for the Joint family. One should leave the children to their own lives. In Rishikesh, I pray and my day is full.”

She wears the traditional white, but distains jewels. Her angelic face is unmarred by cataract-clouded eyes. She exudes goodness and is a joy to be with.

Her husband joined her at the retreat five years ago after deciding the routine wouldn’t impede his interest in homeopathic medicine, garden and books.

With his tall, slender build, long white beard, blue eyes and English twang, Mr. Shivraj, 83, embodies the spirit of the American pioneer. Indeed he did venture to the Missouri School of Mines in 1907 and stayed four years. It was a time when no one went that far, and his family almost disowned him.

Obviously, the Shivrajs are an unusual couple by any standards. They are ageless: Conversant with, and tolerant of the world, eager to learn, and always smiling.

The average Indian satisfies the need for religious experience through pilgrimages, visits to temples and shrines, and ceremonial bathing in holy rivers. He must give alms, make obeisance before the idols and have a Brahmin priest dab his forehead with symbols in vermilion, sandal paste or white ash.

There are about 17 stopovers on the pilgrim special. Some villagers farm for six months, then tour shrines by rail in their free time. Tirupati, in the south, has become the most popular and the richest, with seven million dollars in annual donations.

Hardwar, near Rishikesh and the source of the Ganges River, is esteemed because Lord Vishnu (the preserver among deities), walked there. Evening worship brings multitudes to the riverside to launch leaf boats filled with flower petals and a small flickering wick. The longer the delicate craft survives the swift current, the more auspicious one’s future.

But it is to Benares that one goes to die. The soul reportedly has a shorter distance to travel to paradise from there. This pilgrimage also frees one from the cycle of rebirths; and liberates women from female reincarnation.

No one knows the age of the city. It was ancient when Buddha arrived in 500 B.C. to preach his first sermon. Its center is a twisting, hilly maze of lanes the width of two sofa pillows. It’s a Venice without water, but incredible filth.

BENARES

Open-air crematorium.

The elderly are everywhere, in garments of yellow and white, walking, sleeping, praying, chanting; maybe getting ears cleaned or beards shaved by barbers squatting on the roadways.

Some line the pathways to the river waving aluminum cake pans for doles of money or rice. Others sell yellow and white sacred threads. These worn by the Brahmins, are folded together like shoelaces and look like thin twine used for wrapping parcels.

Still others hawk old coins, or small red clay pots to stow Ganges holy water for a souvenir. There are vendors of sugar cane juice and drinking water, oranges and bananas (dunked in the river as an offering), peanuts, curries and flatbreads.

Streets are jammed with donkeys, scrawny cows and bullocks. Fifty-year-old rickshaw drivers, who look 70, tax strained muscles to bicycle fat grandmothers and their sons uphill towards hotels.

Poor, short-term pilgrims may stay three days gratis in the desolate, grimy Dahrmasala, a Hindu hostel.

Those for whom Benares is a one-way ticket are not much better off. They can rent a closet-size cage with one, tall, barred window facing out on the street. Each dimly lit cubicle contains a dirty floor mat and a human being. Where they go to die.

Just before dawn, the faithful stream toward the river and the centuries-old ritual of bathing, swimming and drinking in the murky waters. With closed eyes they murmur mantras or chants while a priest intones “hari Krishna”, (hail to the Lord) over a loudspeaker.

Some yards beyond, laborers stoke the funeral pyres. Stretchers of yellow or orange, cheesecloth-shrouded forms are massed on a nearby platform. One by one, as the 10 or 12 open-air fires consume the corpses, more are added. Ashes spill into the river.

The mystical hold of Hinduism is difficult for a non-believer to comprehend. It has survived 500 years of stringent Muslim rule and two centuries of the British. “We don’t have to try to understand it,” says a textile factory owner in Benares. “We only have to live it.

“Anything goes,” he adds. “There is no distinction between sacred or profane. Any actions are potential acts of piety. That is why some Hindu temples are covered with pornographic sculptures. Sex is part of life.

“Hinduism survives because it is permissive and absorbs rather than rejects a man. He is free and not bound by the rigidity of, say, Catholicism.”

Since he is not his brother’s keeper, the Hindu is unconcerned about questions of reform and social welfare. If I cringed at human beasts of burden, the lepers, or the sickly old, Indian acquaintances would proffer another scotch and tell me to develop a thick skin. “People are cheaper than things,” one reasoned.

A widow wrote to The Hindustan Times complaining about the inequities of the pension system. (Only13 million persons or about two percent of the population are enrolled in sick benefit or retirement plans. Most of them are government employees.)

Her late husband, after 27 years of civil service, received 1.21 dollars a month pension. Now she receives nothing and has five children to raise, including two marriageable daughters.

The writer is neither an untouchable nor a pauper, but gets no help. If she lived in Madras, and were considered destitute, there is a scheme for those 60-plus to get 2.67 a month. Welfare programs reflect the individual initiative of the 19 states.

In the Indian Onlooker Annual 1971, Tara Menon says acidly, “A welfare state, ensuring the comforts of life to all citizens is still a far-off dream. Particularly in view of the government’s attitude that social welfare work need be attended to only after the country’s economic rate of growth has gone up to around 6.5 per cent. That’s a long way off.

“Social Security,” she adds, “cannot merely be a system of preventing people from dying of starvation, but /should/ assure a full life…embracing…health, education, leisure and culture – all those things, which besides food, shelter and medical services, constitute human life.”

In a poll taken by The Illustrated Weekly, 70 per cent of voters queried saw the future of India as “dark”; only 11.4 per cent, as “bright.”

Nirad C. Chaudhuri, author of The Continent of Circe, and an Indian, comments on the survival of the Hindus. “It is due,” he writes, “to nine-tenths of Hindu society consisting of an inert element…impervious to the active malignancy of the one-tenth. It is similar to the atmosphere in which four-fifths of nitrogen prevent one-fifth of oxygen from burning up the earth.”

The Hindu, he adds, is strong and simple because he refuses to become complex. “The mammoth is extinct, but the cockroach survives.”

Received in New York on January 10, 1972.

©1972 Nada Skerly

Nada Skerly is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star. This article may be published with credit to Miss Skerly, The Cincinnati Post and Times-Star, and The Alicia Patterson Fund.