Slackwater

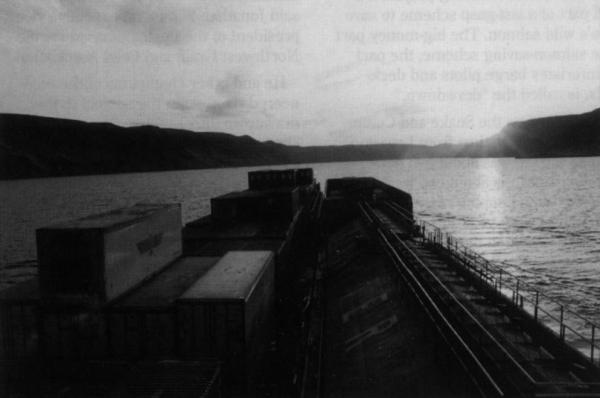

LEWISTON, Idaho -- We sailed west at sunset on water the color of dark chocolate. The sun disappeared slowly into the downstream distance, notching itself between knobby, bald hills and burning out in a long tomato-red smear. The river smelled of the farms it irrigates and erodes, a swampy perfume of mud and fertilizer, algae and a hint of dead fish.

Down in the galley, groggy from afternoon naps, a fat tugboat skipper and a muscular deckhand were playing a quick hand of blackjack, yawning, smoking, drinking coffee, scratching themselves in manly places, and preparing for a six-hour shift of squiring twelve-thousand tons of peas, lentils, wheat, computer games, wood chips, and polyurethane-coated milk cartons out of the hinterlands of the West and off to the consuming capitalists of the Pacific Rim.

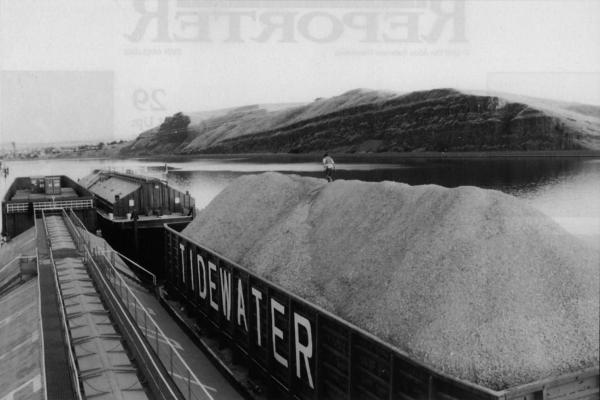

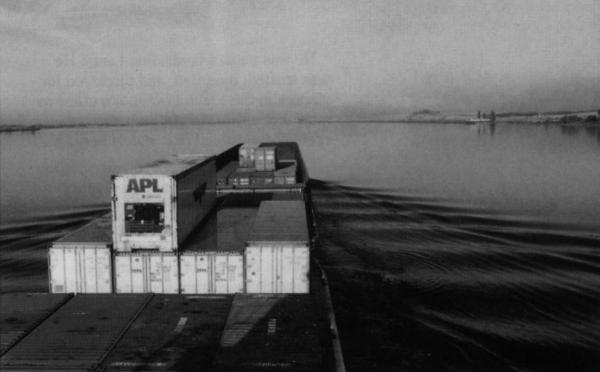

On the splendid September evening that we lumbered out into the middle of the Snake River, the principal tributary of the Columbia, the tugboat Outlaw pushed six barges. The tow, as the ungainly vessel is called, was longer than two football fields and weighed more than a medium-sized office building. Unable to stop in anything less than a quarter mile of still water, too long and too heavy for any other American river, it was a captive of the engineered rivers upon which it plodded.

So, too, were the two men down in the galley, the fat skipper and the muscular deckhand, the ones playing blackjack and scratching themselves. Without federal dams and locks on the Snake and Columbia, they had nowhere to go on their monstrous boat. Without slackwater, they did not have a job, a marketable skill, or a future.

They were, therefore, suspicious of all those they took to be agents for, promoters of, or sympathizers with free-flowing rivers. Their long list of enemies include environmentalists, Indians, fish biologists, wind-surfers, federal judges, the governor of Idaho, federal bureaucrats, salmon fishermen, and suburbanites from the West Side of the Cascades.

The men on the river (they were all men, white men) ate boiled potatoes and beef and ice-cream and sugar cookies. They talked endlessly about their failed marriages and showed each other pictures of their kids. They talk on and on about giving up half their lives to the river, never leaving their tugboats for fifteen days at a stretch, working six hours on and six hours off and always being tired, and going home to lonely wives and confused kids and sleeping fitfully in their own quiet beds, missing the bawl of diesel engines and the jostle of the river. They talked about how the Snake and Columbia sometimes freeze on the coldest winters and how the barges crunch through the ice making a hellish noise like an endless rear-end collision. They talked about the bald eagles that lance down on the river in winter to slaughter ducks whose legs are encased in ice. After eagles attack, the cream-colored ice is stained with feathers and excrement and blood.

Wherever the conversation wandered, it always found its way back to fear and resentment. Deckhands and pilots were terrified of losing their livelihoods to a scheme that would retool the river in favor of fish.

The lower Snake and mid-Columbia, because of federal dams, have been slowed to a lake-like one mile per hour. The more than one hundred white-water rapids that used to torment -- and, on occasion, violently terminate -- river transport from Idaho to the sea have been drowned. Dredges have gouged out shipping channels in both rivers to a depth of at least fourteen feet, five feet deeper than the Mississippi. The difference allows the Columbia Snake System to float barges that are twice as heavy as those that ply the Mississippi. A bushel of wheat travels more efficiently and more cheaply on the Columbia-Snake System than on any river, highway, or railroad in the nation.

One-quarter of America's feed grain and thirty-five percent of its wheat move down these rivers, which have been engineered for freight only since the mid-1970s and which still have plenty of capacity for expansion. If you are a wheat grower or maker of computer games or manufacturer of polyurethane-coated milk cartons and you live anywhere in the West between Grand Forks and Cheyenne and Spokane, federally financed river modification means that there are transport dollars to be saved by forsaking trucks and trains and even the Mississippi and sending your wares to sea in Idaho.

Unfortunately, what saves money kills salmon. Mostly it kills them when they are young and trying to go to sea. An estimated nine of ten juvenile salmon that attempt to swim to the Pacific from Idaho do not make it. Just one adult Snake River sockeye survived the nine-hundred-mile trek in 1992 back up the Columbia and Snake rivers to spawn in Redfish Lake in central Idaho.

He was named Lonesome Larry. He was stuffed, mounted, and displayed for visitors in the Idaho governor's office as a symbol of how "eight lumps of concrete" have ruined that state's heritage.

Lonesome's frozen sperm, along with the fresh sperm of a handful of other adult sockeye males who survived the river gauntlet in 1993, stands between the sockeyes and extinction. The sperm has been used to fertilize about ten-thousands eggs from sockeye females who also made it back to Redfish Lake in the early 1990s. (For all his fame, it turned out that Lonesome's sperm, after thawing out, had "low motility." It probably contributed nothing to the future of his species.) The breeding project is a small part of a last-gasp scheme to save Idaho's wild salmon. The big-money part of the salmon-saving scheme, the part that infuriates barge pilots and deckhands, is called the "drawdown."

Before dams on the Snake and Columbia, the stream-flow time from Lewiston, Idaho, to the sea was about two days. With the dams, it is about two weeks. The drawdown would unplug reservoirs -- for a few months each year during the spring and summer salmon migrations -- and turn the lower Snake and part of the Columbia back into something that is less like a lake and more like a river. Rather than feed the rivers through hydroelectric turbines, the drawdown would spill water over (or perhaps around) dams. In theory, this would whisk vulnerable young salmon to the sea, while protecting them from turbines, predator fish, and the lethal effects of slow-moving, warmish water.

Speeding up the rivers would lower water levels and halt all barge traffic on the Snake for most of every summer, the peak shipping season. It would leave many irrigation systems on the Snake and mid-Columbia high and dry, requiring costly modification. It would cost Northwest utilities tens of millions of dollars to buy electricity lost to the drawdown. Finally, the Army Corps of Engineers estimates it could cost U.S. taxpayers as much as five billion dollars to modify four Snake River dams.

Environmental groups and many fish biologists argue the drawdown is the only chance to save Snake River salmon. The federal government, which has listed three Snake River species (sockeye, spring-summer chinook, and fall chinook) under the Endangered Species Act, has agreed to test the idea. The first test, behind one Snake River dam, took place in 1992 and another is scheduled for 1996. The drawdown could be ready to go before the end of the decade -- assuming that irrigators, utility companies, Idaho port authorities, grain buyers, and barge companies do not succeed in bullying regional lawmakers to kill it.

In trying to stop the drawdown, river-users insist that they do care deeply about salmon. "Salmon are why we live in the Northwest. They are an environmental bellwether of our quality of life," said Jonathan Schleuter, executive vice president of the Portland-based Pacific Northwest Grain and Feed Association.

He and other champions of the engineered river claim they object to the drawdown only because there is no conclusive scientific evidence proving that costly changes in the river will really help fish. They say more basic research is needed. In response, environmental groups smell a sinister strategy of delay. The Sierra Club claims the Army Corp of Engineers, which built the Snake River dams and is running the drawdown, will go on testing until all the endangered salmon are dead.

Out on the river, away from bureaucratic sniping and sham salmon sympathy and polished environmental rage, there was a bracing absence of cant. The tugboat men did not pretend to care about endangered species. They did not believe anyone really did.

Sealed off in a bizarrely big boat for fifteen days at a stretch, missing too much sleep, and eating too much ice cream, they saw salmon as the enemy.

"Nobody wants to give up anything. I don't want to give up my job. The farmers don't want to give up their water. Consumers don't want to give up cheap electricity. I ain't never seen a dinosaur, but I don't miss them. Who says it is not evolution killing these salmon? Who cares anyway?"

So said Greg Majeski, the muscular deckhand. He explained his neo-Darwinian theory of endangered species at the beginning of his evening shift. It was just after sundown and the thirty-four-year-old deckhand had to get out to the bow of the tow to hook up a flashing lantern-style warning light.

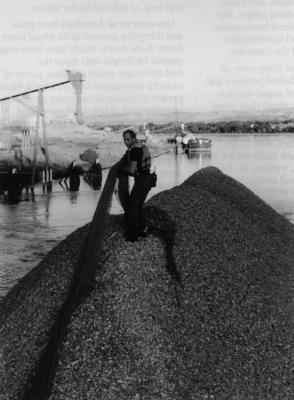

The journey out to the bow was as much an ascent as a walk. Barges ride at different levels in the river, depending on their cargo. The heaviest barge, with three-thousand tons of wheat, sat about four feet deeper in the river than the one in front of it, which had one-thousand, nine-hundred tons of peas, lentils, and computer games. Majeski, wearing a coiled orange electric extension cord across his chest like a bandoleer, hopped, climbed, and shimmied between the barges with the bored nonchalance of a commuter changing trains. He seemed oblivious to the Snake as it sluiced beneath him in the seams between the barges.

Most deckhands slip and fall in the river several times during their career. It usually happens when their tow is near the river bank, picking up loaded barges or dropping off empties. Majeski fell in last spring in the middle of the Columbia. It was at night during a fifty-mile-an-hour windstorm. His radio went dead as soon as he hit the water. His flashlight continued to work and he tried to shine it, while bobbing in seven-foot waves, into the eyes of the tow's skipper, who sat in the wheelhouse forty-two feet above the water and about two-hundred yards from the point where the deckhand fell in. His skipper never saw the flashlight, but was bothered by the oddly silent radio. The skipper managed to find Majeski by scouring the river with a wheelhouse spotlight. Then he turned the tow so Majeski could pull himself back on board. The deckhand changed his clothes and returned to work.

After fourteen years on the river, Majeski's job, which pays him about forty-five-thousand dollars a year with overtime, has given him the body of a linebacker -- hulking shoulders, tree- trunk arms, tight waist, powerful legs. Out on the barges, his primary responsibility is to tie, untie, and tighten the cables that hold the tow together. The cable is an inch-and-a-half thick and a foot of it weighs fourteen pounds. Dragging forty feet of cable across a barge means wrestling with five-hundred and sixty pounds of not-very-flexible steel.

Deckhands, as they age, suffer from chronic tendinitis, bad backs, torn shoulder ligaments, and aching wrists. High winds on the river can snap a cable like a rubber band. A flying cable can shatter or severe limbs. There is also the risk of getting a foot, leg, or arm caught between barges, a squeeze that can turn appendages to mush.

Out on the bow, the evening was fine and warm, with little wind. Majeski had left behind the incessant wail and vibration of the tugboat engines that push the tow. The barges splashed, with a soothing sibilance, through a darkening, glass-smooth river. The Snake, as it enters Washington State and heads west towards its confluence with the Columbia, flows through a steep, arid, and oddly empty canyon. Its steep walls have no trees and very little vegetation. They seem, from a distance, to be covered in elephant hide -- dirty grey, cracked, and gullied by long-ago rain. There are irrigated wheat fields and vineyards and small farm towns up over the canyon lips. But none of this can be seen from the river.

From the bow of the tow, night passage on the Snake was serenely disorienting. The darkness was unearthly, like sailing in a cave.