The Politics Of Textbooks

AUSTIN, Texas -Chapter 25 of "World History, Our Common Heritage" deals with the industrial revolution. Understandably, it's devoted mostly to the influence of Karl Marx. And it's illustrated with pictures of four people.

Florence Nightingale. Elizabeth Fry. Charlotte Bronte. Ludwig von Beethoven.

Marx's impact couldn't be ignored. But since Marx's socialistic message rivals only Charles Darwin's theory of evolution in generating controversy, his powerful image could be left out to soften the blow.

In its place would be substituted pictures of three non-threatening women. This would satisfy the feminists, who keep running tallies of gender illustrations. And it wouldn't disturb the Daughters of the American Revolution, either.

A publisher can't get safer than Florence Nightingale.

The textbook, published by Ginn, was not unique among the eleven world history books under consideration for use in grades 9 through 12 in Texas high schools. Only five books contained a picture of Marx. But this book -and the way it was selected for Texas schools last summer -are symbolic of what is happening in the nation's $1 billion-plus textbook industry.

Ever since the Greeks used Homer's poetry as the first instructional volume, textbooks have represented the most stable and traditional way a society preserves its cultural heritage. They reflect a nation's common values, goals and priorities. They're a mirror of what society considers acceptable.

In the United States, textbooks provide a common body of knowledge to a mobile population. They underscore evolving attitudes. They are what we know, and what is important to us. They are controversial and will always remain so because this is a free society where differences can be expressed, and where local control of education is one of the nation's fundamental underpinnings.

The struggle is at least a century old. One of the first complaints against textbooks came from Northern Civil War veterans who resented the way history textbooks of that era were depicting the South. For a time in the 1900s, two sets of textbooks were used in the country, one in the North and one in the South.

The essence of the dispute remains the same. Critics contend that young minds are being poisoned or weakened. The critic believes that his view of the facts is the correct one and that it must be substituted for what is in the books.

These concerns range from complaints about the portrayal of big corporations; whether women are shown as astronauts or homemakers; how slavery in the South is depicted; and whether the American Indian either spent all his time scalping settlers or was part of a very sophisticated civilization.

Issues such as whether the "communist menace" is handled harshly enough in textbooks will never change. Other issues are very topical, such as California's ban on pictures of "junk" food.

There have been changes in the critics themselves. The DAR is still there, complaining about everything from softness on Communism to failure to reinforce the traditional roles of women. The complaints of blacks and feminists are not as strong as they were in the 1970s, when Congressional hearings on how educational funds should be used brought new impetus to complaints about racial and sexual stereotypes.

What is new is the broad support many of the grassroots groups receive from established conservative organizations such as the Moral Majority, the Heritage Foundation, Phyllis Schlafly's Eagle Forum, evangelical groups and television preachers. It can be in the form of funds, information, "action kits," or just the legitimizing of the critiques churned out by longtime textbook foes Mel and Norma Gabler of Texas. Now, national conservative figures are espousing the same philosophy. Education is a cohesive rallying point. Many parents concerned about the quality of education eagerly join the "back to basics movement."

Suddenly, a steelworker, worried why Johnny can't read or write, is supporting a challenge to school materials by a group which, in another forum, espouses a free-enterprise, anti-union stance.

The specter of illiteracy has enabled many mainline conservative groups to expand their influence and garner new support for their long-standing goals -school prayer, anti-busing, anti-abortion, and tuition tax credits. Paul Putnam of the National Education Association describes this campaign as an "appeal to fear" in order to "take over" the school system. "They attack books to draw attention and the next thing you know they are running for the school board," he said. "When you control the child, you control the country."

These challenges are gaining new force because of their success in several key states with statewide book adoption policies. Since it is too expensive to publish more than one edition of a text, the decisions made in these states will largely determine what textbooks this country's 39 million elementary and high school students will use.

This ability to influence how millions of dollars will be spent necessarily affects textbook publishers, whose ownership has become increasingly concentrated in large corporations where profits often overrule principle.

Texas, and other large states that approve books before local schools can purchase them, have become the magnets for challenges to the content of books. A century ago, an organized purchasing system was a way for a state to negotiate a fixed, and cheaper price for school books. It also improved the quality of books used in rural areas. Now, such a system is more concerned with ideology.

In the 22 states where the adoption is centralized, critics, organized and otherwise, have a better chance to air their objections and, consequently, to have some impact. First, they can lobby against a book using political tactics. In Tallahassee, Florida, last year, a pro-family forum took out a full page newspaper ad, and arrived en masse at the selection meeting, with bumper stickers and buttons all containing the message: "Public schools: clean them up or close them down." Their target was sex-education books.

Curriculum Guidelines

An increasing number of states now adopt a proclamation, or set of curriculum guidelines that detail the requirements which textbook publishers ignore at the risk of having their book rejected. It is through old fashioned politics that critics get their members on these selection committees.

For example, in at least 25 states, a science text cannot be purchased if it does not mention alternative theories of evolution. In response to these proclamations, it is more likely that the publishers themselves will make the accommodation even before their books are submitted for adoption. This lessens the burdens of those who support creationist beliefs, and also deflects the charge of censorship back to the publisher.

(So great is the pressure on biology and other science books that their very integrity is being strained, according to education processor, Gerald Skoog. In a study presented by Skoog in July, 1983 to the National Institutes of Science, the word "evolution" and the presentation of it as a leading scientific theory in textbooks has declined.

In more recent books, the word "evolution" has all but disappeared from the word glossary or chapter title. Other books, Skoog said, have about as much coverage of evolution as textbooks did in the 1950s.)

Another reason why textbook critics concentrate in the large adoption states such as Texas and California is the relative ease of legally stopping a book there. It is better to go after a book before it is bought, than after it is in use in the classroom. After the fact, a challenger would have many more procedural obstacles in getting himself heard, the book would be entitled to many First Amendment protections and a victory might only affect a small school district.

There is also the simple power equation. At which point does the opposition have more influence? Surely it is when the publisher has million dollar profits in the balance.

Most publisher's representatives are reluctant to talk at all about the politics involved in their work, and those who do talk don't want to be identified. "If they back us up against a wall and say, You either take it out or you won't sell the book in Texas,' then we'll take it out," a member of Doubleday's textbook division said.

Textbook Hearings

"In all cases I am asking for information to be added, I'm definitely not asking that the books be censored," said Mrs. Larry Waldrip, a witness at the Texas textbook hearings held in Austin in August, 1983.

Mrs. Waldrip contended that an obscure, untranslated diary of Christopher Columbus revealed the real reason why Columbus set forth on his journey to the new world. "There is no question it was a message from the Holy Spirit that made him do it," said Mrs. Waldrip, who is president of a suburban school district in central Texas.

She was one of more than 30 speakers who urged the state textbook committee to adopt, reject or demand changes in the proposed textbooks up for adoption last year. She spoke to 23 members of the textbook committee, and before seven television cameras and dozens of newspaper reporters.

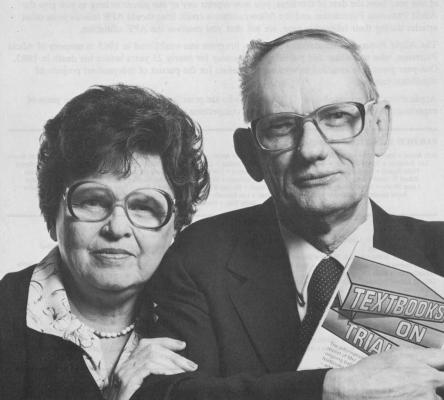

But the television cameras don't go on and the reporters don't sit straight up until Mel and Norma Gabler are ready to speak. The "mom and pop" textbook critics have become national figures as a result of their success at these hearings during the past 20 years.

At the 1983 hearing, Mel Gabler, a thin, frail man who speaks softly, highlighted factual mistakes in world history textbooks and demanded more emphasis on the American Revolution. Last year, as in the past, the Gablers found examples of how publishers have "conceded" to the demands of feminists and minorities. In one text, protested Gabler, students are told to research biographies of women during the French Revolution. "This activity shows obvious bias and editorialism. Why aren't students also encouraged to research any men of the revolution?" the Gablers questioned in their petitions.

The Gablers generally complain about open-ended questions that force students to draw their own conclusions, downplaying of the free enterprise system, positive pictures of socialist countries, sex education, emphasis on any religion other than Christianity, depiction of women in non-traditional roles, and presentation of evolution without any mention of creationism.

It is Norma Gabler, a grandmotherly figure in a polyester pants suit and polka-dot blouse, who first protested at hearings 20 years ago. While she is considered the major force and organizer in the family, she defers to her husband in the public roles.

Mel Gabler contends that he is concerned about the quality of the books. He stresses concentration on basic subjects. One of his favorite anecdotes concerns a high school graduate at the supermarket checkout counter who cannot make change for a $10 bill.

But the Gablers, who have formed a non-profit corporation called Educational Research Analysts with full time readers to review the texts, also have another reason for their crusade.

"'The vast majority of the public has a value system that is different than what is taught in the textbooks," said Gabler in an interview during the hearings. He said he has seen some improvement since he started his campaign but still has no cause to ease the vigil.

"Many of the books have the same amount of questionable content, but they are much more subtly written. They require much more careful examination," said Gabler.

Last year the speakers were allowed only six minutes, a reform mainly directed at the Gablers who often captured the podium for hours and days in prior years. The time was kept by a clerk who has a picture of a clock dial projected on a screen. With a timer in one hand and a red arrow in the other he jerkily ticked off the minutes.

While Texas ranks fourth in national dollar expenditures on textbooks, the $65 million it will allocate for the 1984-85 school year is still influential. Texas school districts can only order books on the approved lists. Texas is also the only state where tax revenues are specifically set aside for books. There is no uncertainty about waiting for a state legislature to appropriate money.

For publishers, a place in the textbook list can account for 12 to 30 percent of their total annual sales. Like "banned in Boston," approved in Texas has a cachet to it that influences other school district selection. This is especially true in the South and Southwest, where many of the other states with similar state-wide adoption systems are located.

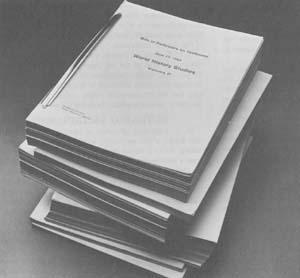

The Texas summer hearings are only a showcase for months of research and pages of written materials. When a publisher makes a book available for adoption, it must supply 23 copies to each of the educational districts in the state. Anyone can review the materials. Written critiques, called "bills of particular," are then filed with the board. Publishers and others can reply to the complaints, and then the petitioner has right of rebuttal.

At last summer's hearings, Mrs. Eleanor Hutcheson of the Texas chapter of the DAR said the history books did not reflect the complete truth about communism. "They are too lily white on communism, too rosy on China and they don't even mention Poland," she said.

Another speaker complained that a book which declared that women's clubs founded most of the libraries in the United States "attempts to indoctrinate in the women's lib ideology."

To show the publishers that they are still watching and counting, representatives from the National Organization for Women said there weren't enough women depicted in fulfilling and challenging careers.

Some of the watchdogs work alone, such as Elizabeth Judge of Houston. Her doggedness of local officials and textbook publishers, and her frequent newsletters on behalf of minorities and feminists in textbooks rivals the fervor of her conservative counterparts. She was critical of one history text because it "illustrates the beautiful Nefertiti but omits the powerful Hatshepsut." Nefertiti was an Egyptian queen known for her beauty while Hatshepsut's wise leadership earned her the reputation as one of Egypt's most outstanding pharaohs.

Judge is basically concerned with the stereotyping of minorities, and treatment of women. She speaks out against the failure to mention persecution of women as witches.

(Witchcraft is one of those dangerous concepts that makes a publisher vulnerable to the argument that the book teaches the occult. Last year in Alabama, a grade school book used by roughly half of the country's school children was banned. The review committee contended that book promoted the occult, because of a reference about a Halloween witch costume. The book, "Basic Goals in Spelling," was also rejected after critics cited a reference to the Equal Rights Amendment in a baseball story. The ERA reference was actually about a pitcher's Earned Run Average.)

Last year was the first year that Texas residents could speak in support of a book, a reform engineered by People for the American Way, a group funded by television producer Norman Lear which has become a formidable balancing force in the state hearings.

Michael Hudson, coordinator of the group's Texas project, didn't make any specific recommendations, but rather pointed out examples in the books that encourage independent thinking, discussion and tolerance of differing views. "What we seek, very simply, is that the decisions of the Textbook Committee be based on valid education grounds and not on partisan ideology," said Hudson.

After all the petitioners spoke, the publishers' representatives were given a chance to respond. They had already submitted point by point rebuttals in writing. Most behaved like defendants waiting to be sentenced. Some were silent, passing up the chance to plea, hoping it would soon be over. Some were contrite, like Charles Compton of Ginn, who said he would be "willing to negotiate with the agency."

Others were defiant, like Michael Shaw of Houghton Mifflin, who brought an author and a consultant with him to point out that their English books were on 14 other state lists and that more than 2 million students use them.

The textbook committee, which consists of one member from each of the state's 23 Congressional districts, votes for at least two and no more than five books in any category. The hearings are a model of democracy in action and often praised by publishers. However, it is further down the line where this process can be subverted.

The committee passes along its list to the State Commissioner of Education who decides whether the texts conform to the proclamations. He can veto any book. His recommendations are then sent to the state board of education, which also can eliminate books from the list.

It is at this point, behind closed doors, that the commissioner and state board can negotiate with publishers to make changes and deletions, accuses Barbara Parker of People for the American Way.

In the past, Parker said, health texts were rewritten to make a stronger case against marijuana use, additional historic documents were included in history books to make them more patriotic, and questions were deleted from end of the chapter summaries.

In 1982, Raymon Bynun, the education commissioner, objected to both of the two recommended dictionaries -the Merriam-Webster collegiate version and the American Heritage Dictionary published by Houghton Mifflin. Bynun said the books contained vulgar words, which weren't justifiable. Merriam refused to delete the words.

Outdated Dictionaries

W. A. Llewellyn, president of Merriam Webster reference books, a firm not heavily involved with textbook publishing, wrote a strong letter to Bynun about the need to trust a reference source: " When you go to it seeking answers, you can be sure that whatever you find there is as free of personal bias as we can make it. There is, however, a cost for this assurance that we don't give in to someone else's pressure. It is that we won't give in to your pressure."

Although the other publisher, Houghton Mifflin, agreed to remove the offending words, the state bought no dictionaries in 1982. State law requires that at least two books in each category be approved.

There was a similar dispute in the 1977 dictionary adoption year involving obscenities. Again, dictionaries weren't purchased. The dictionaries currently in use by Texas school children are copyrighted 1969.

The Gablers are so influential at the latter stages of the book selection process because their supporters have won election to the state board of education. One member wholly on their side is H. Reg McDaniel of Dallas. "If they (the Gablers) hadn't been doing it we would have had to hire a lot people at taxpayer expense," he has said.

His message about back to basics, spelling bees, and memorizing multiplication tables is appealing and typical. "We are letting hard basic education slip. While we've been concentrating on a better and better football team, the Japanese have passed us by,"' said McDaniel. But critics also display an underlying attitude of distrust for teachers, school administrators and instructional materials.

These professionals have been taught and trained by university professors with "irreligious and socialistic" beliefs, said McDaniel, causing our classrooms to contain "ideology that is contrary to everything this nation stands for."

McDaniel, who said he ran for the school board after he became aware of the anti-capitalist, anti-busing bias in the schools through his local Chamber of Commerce, asks parents to become involved. "Have you read a public school textbook lately?" his literature asks. "Do you know the ideas, ideals and attitudes your child is being taught?"

Elementary and high school texts represent a $1 billion business, according to the Association of American Publishers. This very small industry sees an average of 10 percent in profits, but it is still big enough so that one state doesn't make all that much difference, according to Donald Eklund, vice-president of the school division of the publishing association. "If a book doesn't make the list in Texas, it is not doomed to be an economic failure," he said.

But he acknowledges that changes are made in the editorial content of a book to appease the critics. "Some will and some won't," he said. "A publisher has to make some conscious decisions," said Eklund, "knowing full well that it will sell better in some parts of the country than others."

(Editing content for the marketplace is not a recent development. For decades Shakespeare's Othello was not included in literature anthologies because the South would not accept miscegenation.)

Like practically everyone else involved in the process, Eklund rejects the label of censor for publishers. The 23 school textbook publishers his organization represents are the best example of the free enterprise system, he said. "Some publishers will choose not to participate (with demands to delete, change, edit) if it is too offensive to them."

But to whom and when the label of censor is best applied really ignores a very important question: the consequence this atmosphere has on the quality of the books themselves. School children spend between 75 to 90 percent of their time with textbooks in school and in assignments at home.

Are the necessary changing interpretations of history to be made by scholars and academics? Or are they to be a bland patchwork of information and pictures not considered offensive to anyone?

The concern about the criteria for textbooks comes at a time when the quality of education is a critical national issue. The recent report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education suggested the one way to stop the mediocrity in our schools was to use textbooks that present "rigorous and challenging material clearly."

Another significant report, released last September, found that too much emphasis was being given to basic rote memorization and the use of unchallenging and stultifying instructional materials. The study, by noted education specialist John Goodlad, said, "The schools did not appear to be...developing all those qualities commonly listed under 'intellectual development': the ability to think rationally, the ability to use, evaluate and accumulate knowledge, a desire for further learning."

The timidity of the current texts about open inquiry and controversial facts has attracted diverse critics, including some who could be hardly called liberals.

Ernest Lefever is director of the conservative Washington think tank, Ethics and Public Policy Center, which has published three textbook critiques. "There is perhaps only one way for textbook writers to avoid the slings and arrows of outraged teachers, parents and scholars," Lefever wrote in an introduction to one of the studies on values in American government. "They can serve up a bland and balanced diet of contested views which may beguile potential critics but is certain to bewilder pupils."

But Mount Holyoke College politics professor Christopher Pyle says good textbooks should force students to defend and thereby reconsider ideas that they have accepted uncritically from families, churches, governments and industry.

"Our society purports to value education," said Pyle, "but training is what it usually wants."