Maine's Faustian Dilemma

Yale University's David M. Smith, the country's preeminent silviculturist, once believed it was impossible to clearcut the Maine forest so totally that it wouldn't immediately renew itself naturally. "I was wrong," he now says with dismay. "I underestimated the impact that heavy-handed clearcutting with ponderous logging machinery could have." On logged-off sites in the northern spruce and fir region which Smith has observed, there is no regeneration of those two commercially valuable species; instead, junk vegetation has appeared.

Smith said either the large harvesting equipment destroyed the juvenile spruce-fir that would have grown up to be the future forest, or the standing timber was so young when it was cut that an understory hadn't taken hold. "In any event, there are places where people who own the land seem to have forgotten how dependent the Maine forest is on [the new] growth," said Dr. Smith, a professor at Yale's School of Forestry and Environmental Studies for 38 years, author of the leading silviculture textbook for foresters, and a consultant to the Baskahegan Company, which owns 100,000 acres in northern and eastern Maine.

To Smith, the regeneration failure is proof that the forest can be wrecked beyond its ability to recover, at least in the near future. Behind such exploitive practices is a firm policy of "get the wood to the mill as cheaply as possible and leave it to nature to heal the wounds," he said. That policy, Smith believes, is welded to the industry's obsession with quarterly, and annual, reports. It pits quick profitmaking against the needs of the slow-growing forest that can only be harvested every 40 to 60 years, he said.

In the face of short-term goals by financial decision-makers, company foresters do what they are told and provide no counterforce to "the moneybags," as Smith calls the business school graduates now in charge of many major forest products companies. He is critical of such expediency on the grounds that it is the antithesis of true forest management and goes against a deeply held ethic that the forest is a renewable resource the present generation only borrows from the next one.

The situation does not reflect a diehard industry position against careful harvesting or against substantive investment back into the forest, according to spokesmen for pulp and paper companies with timberlands in Maine. They maintain they would like to have that option but are limited by economic realities key to their companies' survival.

For example, Andrew C. Sigler, chairman of Champion International Corp., says he is pressured to reinvest in ways that make the company stronger on the stock market and less vulnerable to unfriendly takeover-and that slights forest renewal programs. And, financially ailing Great Northern Paper Co., Maine's largest landowner, recently terminated its forest improvement programs in a move to survive the short-term period. President Robert F. Bartlett says the company will save "a great deal of money" by cutting out its reforestation, tree nursery and herbicide spray programs. International Paper Co. woodlands manager Robert Hintze said he doesn't think there's anything unethical about a company limiting its forest renewal programs. "That's just business," he said.

Clarifying his position, Smith submitted that corporate penny-pinching on forest renewal has led to "silviculturally true clearcutting," that is clearcutting in which a site is stripped. It is the least expensive way of harvesting, he said, because the forest can be, in effect, mowed down, and costly road-building is not necessary. Today's massive equipment, capable of removing whole trees, sweeps down the young trees rising up from the forest floor, and it sets up conditions for weeds to flourish. Harvesting is done on a year-round basis, subjecting the earth to erosion and scarring.

Before the 1970s, there was harvesting called clearcutting, Smith pointed out, but in actuality it was "highgrading," taking the best trees and leaving behind the smaller ones and species of no commercial value. He said it was less injurious to the forest as a whole because it used small harvesting equipment and horses "that didn't roll over all the advanced regeneration," and cutting was done in the winter when damage to the soil was minimized.

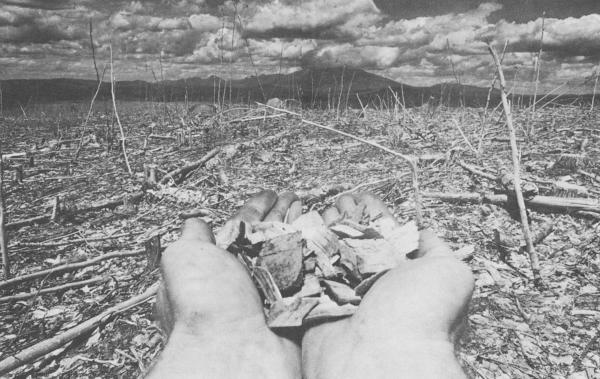

The impact of true clearcutting on the landscape is startling. Flying over the huge industrial forest, the freshly denuded sites are visible for miles; the ground appears orange, in sharp contrast to the dark green of the surrounding "Christmas tree" conifers. (The orange color is not in the soil but is the tannin pigment in the slash, or timber debris left on the ground after logging.) Maine Forest Service ranger Roger McLellan, who routinely flies over much of Great Northern Paper Company's 2.1 million acres, says, "You could plow some of those heavy clearcuts like farmland if there were no stumps left in the ground."

Other places where true clearcutting took place a few years ago look like silvicultural slums, growing up in pin cherries, red raspberries and other brush. The only remedy is costly replanting, and it usually isn't done. But when areas larger than about 20 acres are subject to clearcutting without replanting, it is often perilous to the forest, its wildlife, water quality, and other public values. Consequently, it is the most controversial kind of harvesting.

Neither Smith nor other foresters who have seen the overcutting knew how widespread the regeneration failure is. The state collects no information on harvesting practices, and the industrial owners' official news office had no explanation, saying it was waiting for the state to do something. There are no reliable figures on how much money the major owners (industrial and non-industrial) are investing on forest improvement. Some money is being spent on planting, thinning, spacing, fertilizing, brush-cutting, and herbicide spraying. But the public doesn't know if the dollar investment is $100,000 or $1 million a year.

The level of private investment is important because together the industrial and non-industrial timberland owners hold almost half of the state of Maine -the highest proportion of industry ownership in the U.S.; there is little publicly owned commercial forest and less public land than in any other state.

One estimate asserts that no more than 50,000 acres in the eight-million-acre industrial forest annually receive the benefit of "silviculture," defined as the science and art of growing, tending and renewing a forest. Dr. Robert Seymour, a silviculturist at the University of Maine who came up with the 50,000 acre figure, said most of that acreage is sprayed with chemical herbicides to kill off undesirable hardwoods to "release" the understory of spruce and fir, prized for papermaking. And, Great Northern Paper Company alone has sprayed 24,000 acres out of the 50,000-acre total.

Seymour said only "a very small amount" of timberland is "improved" in Maine's other eight million acres of timberlands. In all, he calculates that no more than 60,000 to 70,000 acres, or less than one-half of one percent of Maine's total 17 million acres of timberlands, receive any benefit from renewal programs. Yale's Smith said, "Simple logic tells you to look at harvest and regeneration as one step."

Despite the uncertainty concerning long-term sustainability, there has been no pressing demand from the public to know what the large landowners are doing -even with the extensive media coverage of the more extreme clearcutting following the last decade's spruce budworm devastation. (The budworm, endemic to the spruce-fir ecosystem, explodes to epidemic proportions every few decades.) One and a half million acres of spruce-fir were killed, necessitating timber salvage operations. In the decade preceding 1982, woodcutters leveled between 500,000 and one million acres of timberland, according to the Maine Forest Service.

Even if the non-regenerated clearcuts are not typical of the majority of timberlands being harvested, the quality and speed of forest renewal remains an issue because: 1) the once high-quality forest is in the poorest condition in history, resulting from past "mining" of the valuable white pine, white and red spruce, and hardwoods, and leaving the land vulnerable to proliferating weeds -raspberries and pin cherries; 2) Maine is facing a predicted shortfall of spruce and fir within the next 20 years and won't be able to sustain its number one manufacturing industry, paper products, at current production levels; and 3) the appearance of unregenerated sites is evidence of a potentially serious species conversion of important softwoods, such as spruce and fir, to commercially valueless hardwoods and brush.

"But how do you get people stirred up about all this when the forest is so abundant and has held up so well to past cutting?" Smith questions. "Forest improvement has seemed so irrelevant," in a state where overabundance had been the only regeneration problem. He said the decline has occurred so slowly that "people don't remember how good the forest was, how it has been whittled away." The public aside, Smith said, "a lot of [the landowners] haven't woken up to the fact that from here on out they've got to consciously grow the stuff...because they are finding smaller and smaller trees and poorer and poorer ones.

Forest economist Charles Hewett, once a student of Smith's and now director of the Maine Audubon Society, explained how important the perception of forest abundance is. The forest inventory sets the delivered price of wood to the mill. The total volume of wood in the forest is 50 times the current growth rate, Hewett said, and it commands low prices because the market registers it as abundant, and readily available. The catch is that suddenly the annual cut of balsam fir is greater than the annual growth, in fact 50 percent more. But that important fact "never gets worked into the equation, and by the time the inventory shrinks to reveal the negative removal/ growth rate, it's too late to take steps necessary to correct it," Hewett said. Since the average growing cycle for a softwood or a hardwood in Maine is four to six decades or more, it takes a long time for forest improvement measures to have an impact.

"We're in a real Faustian dilemma," he said. "It's not attractive to landowners to invest in forest renewal [because of the large inventory]. And, as the inventory stops obscuring cut/growth ratios, wood costs will skyrocket, and there will be even less incentive to invest in the forest. What we will see happen, I think, is a tremendous rush of mergers and foreclosures," Hewett predicted.

Yale forest economist Clark Binkley characterizes Maine as "having gone down a dead-end street" without forest renewal, "and you just can't turn around and back up. Something has to be done!" He agreed with Dr. Seymour that "the science has been worked out so we know what to do about it. It's the shortage of investment money and the will to do it that is lacking," said Seymour.

Binkley believes that Maine may have to consider subsidizing forest renewal on private lands. "Without it, silviculture is simply too expensive on a large scale," he said. And, it's scary. Putting money into timber improvement ties up scarce capital that doesn't yield a return for decades and is beset with risks. Too, it's a highly illiquid investment. For those reasons, forest industry profits are increasingly being directed to the manufacturing end of the paper and wood products business, rather than to trees, which are essentially invisible to stockholders.

Luke Popovich, vice president of the American Forest Institute in New York, recently attested to the waning concern for the future forest on a national scale, even by those who have been leaders in forest renewal, such as Weyerhaeuser Corporation. They are contemplating sharp reductions in their silviculture programs, he said, because of the tough financial problems plaguing the industry, from stronger foreign competition to a worldwide paper glut.

Until the late 1970s it was impossible, even for company foresters with foresight, to convince the corporate decision-makers that forest renewal was a subject worth much discussion. The traditional thinking was Maine had too much regeneration of softwoods and hardwoods, and the forest had exhibited a remarkable bounceback capacity, no matter how it was cut. Since the harvest didn't come near to exceeding the growth, cutters could take what they needed, move on to a new area, and let nature leisurely replenish the supply in the continuing cycle of growth and removal. Based on that large forest inventory, market demand, and the expected quick recovery capability, the pulp and paper industry overbuilt its operations during the decade of the 1970s.

During the last decade, landowners were too busy "chasing the budworm" to think about managing timberland to assure its sustainability. "But thank God for the budworm, in a sort of backhanded way," said Dr. David Field, a University of Maine at Oronoc forest economist. "It was the first sledgehammer that woodland managers in the 10 million-acre spruce-fir region had had in a half a century to catch the attention of the chief corporate officers. All of a sudden, with computer models forecasting a shortfall, the folks in the corporate office realized they could actually run out of wood. They never believed that before," he said.

Shaken up, the companies spent millions of dollars to expand the road system to salvage budworm-damaged wood and to provide access necessary for future forest improvement work. On an experimental scale, landowners began to spend $50 to $200 an acre to carry out various "silvicultural prescriptions" to see how the forest would respond. Company foresters from the manmade pine plantations in the South and the intensively managed timberlands in the Pacific Northwest were transferred to the Maine woods operations, raising some people's hopes that a parallel corporate commitment to forest renewal in Maine would be made. Some felt it was simply Maine's turn for investment money, since so much had been poured into the South and Northwest for 30 to 40 years.

Although there are some isolated cases of exemplary forestry being practiced on Maine's timberlands, the hoped-for investment hasn't occurred on a scale that could turn around the present situation. Especially now, in profit-poor times, stockholders want to see investments that will result first in increasing earnings, not in good citizen awards for growing big trees. International Paper's Hintze was frank about the cost pressures on him: "I can only be as ethical toward the land as economics will allow me."

Also, in the last decade, technology has proven to corporate decision-makers that it can bail out bad forest practices, and species shortages can be overcome without spending a lot of capital on forest renewal. When there was a shortage of peeler logs for plywood, technology created glued "chip sandwiches" to make waferboard and oriented strand board, and technology also allowed low quality hardwoods to be used as a filler in paper traditionally made from softwood fiber. It has instituted a new acceptance of reconstituted wood products as an acceptable change from whole wood products. While reconstituted products have filled sawlog gaps, prices they command are far less than those for high-quality logs.

Besides being in a "Faustian dilemma," as Audubon's Charles Hewett calls it, Maine is in a Catch-22 situation. The wood shortfall is expected to hit just as the demand for wood is expected to be rising. By 2030, the consumer demand is projected to double, but without a "major improvement in managing the forest," even the current harvest of about six million cords can't be produced on a sustained basis, much less doubled, said Maine state economist Lloyd Irland. Yale's Binkley said that increasing demand is why "the imperative of sustained yield has to be followed in the good times and tough times and regardless of changing circumstances."

Productivity studies have shown that Maine and other states in the region are capable of producing twice as much wood as they do now -if investment is made in intensified forest management programs. The future demand could be met, Irland believes, but it would take 50 years -and a lot of money -to upgrade the forest to that potential.

Renewal always comes back to financial commitment. The record of Maine's 180,000 small woodlot owners -the non-industrial owners who control 49 percent of the commercial timberlands -is historically terrible on investment in the land.

Some forest company officials have openly complained about the increased pressure they feel. Champion International chairman Sigler said: "Everything is pegged nowadays to increase earnings. It costs us a billion dollars and takes three years to build a paper machine. I'm always criticized that I should use that money to buy back my stock to boost earnings per share. There's a pressure that you can't ignore, and it's counter to whatever is good for the country." The recent merger fever has made managers fear that if their quarterly results are weak, their stock prices will plummet so much that their companies will be ripe for takeover.

Economist Field said the situation doesn't make the companies and stockholders unconcerned about the forest, but their concern for it is primarily for its role as a fiber generator. The growing bias against the importance of tree size and quality makes it tempting for managers to reach production quotas with a minimum of costs, because the way the forest is treated won't be felt until decades later when the owner may no longer bear any responsibility for the resource, Field said.

Why haven't foresters spoken up and made forest investment a public issue? Silviculturist Smith and economist Field said foresters are generally reticent types who aren't interested in the financial side of forestry. "They want to go out and grow trees and they don't like economics, financial analyses, and taxes," Fields said. "They haven't been effective promoters of forest improvement."

Yale's Binkley relates the silent forester problem to the issue of accountants and attorneys running forest products companies. There is widespread concern, not just in Maine, that the industry leadership is now in the hands of people untrained in forestry who don't "understand" the long-term nature of forest management. Binkley isn't worried so much about the accountants and attorneys at the top, but rather the problem that few who know forestry are communicative enough or "trained well enough on the business side of the operation to be able to effectively bring reasonable arguments to management."

Smith confirmed that "with some of these outfits, the communication between the top and bottom is about zilch. In fact, there are so many of these foresters accustomed to taking orders from on high that they don't question. They just go on drawing their pay and saying it's not their fault. Actually, it would be better if they had the attitude that if management doesn't want to fund it, how else can we do (renewal). There are plenty of how-elses' " Smith asserted.

Yale, Syracuse University, the University of Minnesota, the University of Maine, and other leading forestry schools have tried to improve the situation by offering students programs to obtain simultaneously their Master of Business Administration and forestry degrees. The programs are designed to give them a competitive edge against economists, lawyers, accountants, and chemical engineers working their way up the forest company hierarchy. "If we turn out foresters who only understand the ecology, the moneybags people are going to run away with the ballgame every time," Yale's Smith said. "Forest renewal will continue to lose out."

While a few foresters are learning the language and the political nature of business, the opposite is not happening. Smith said he doesn't know of any schools that require business graduates to take courses in resource management or stewardship ethics. "It's not easy to weld these worlds together, especially when the whole sociopolitical system wants to stack the deck against good forestry," he says.