Crime and Impunity in Chile: Perverting the Law of a Legalistic Land

Item: A teacher is kidnapped by the secret police, and his family files a petition for judicial protection, which is rejected after the government asserts the man is not in custody. Several months later, he is found in a prison camp, recovering from torture. The court requests an explanation, and the government replies that its original statement was the result of an "administrative error." Satisfied, the court rejects the family’s petition again.

Item: A prominent politician is ordered expelled from the country by government decree; he appeals the order on grounds that the decree is unconstitutional. While the appeal is pending, the military junta issues a new law saying that any previous decrees found to be incompatible with the constitution will now automatically become amendments to it. The court rejects the appeal, and the politician is flown into exile.

Item: A judge is named to investigate the disappearances of 12 Communist Party members, all of whom were reportedly seized by state intelligence agents. After a long investigation, the judge charges a number of current and former military officers with kidnapping and conspiracy. The Supreme Court dismisses the case, citing a law granting amnesty for politically linked crimes. The judge refuses to halt his investigation, and he is suspended from the bench for insubordination.

These incidents, all of which have occurred in Chile since the military coup of 1973, illustrate patterns that have characterized judicial behavior throughout the rule of General Augusto Pinochet: a tendency to accept without question government statements and decrees, to flout the rights of dissidents while carrying out the letter of the law, and to punish attempts by lower-court judges to pursue human rights abuses.

For generations, Chile's justice system was a model of civilized behavior in a highly legalistic and democratic society. But with the military takeover this proud tradition seemed to be forgotten; the majority of judges turned a blind eye to massive political repression and became accomplices of dictatorship "by omission," as the Inter-American Human Rights Commission stated in 1985.

Accepting without question the government's contention that a legal "state of war" existed after the coup, the courts thus relinquished their right to act as a check against excessive executive powers. For years, the Pinochet regime continued to invoke various legal "states of emergency" which authorized it to use sweeping repressive measures against opponents.

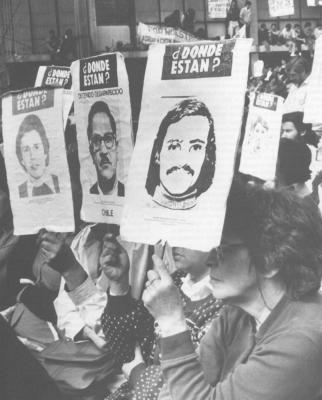

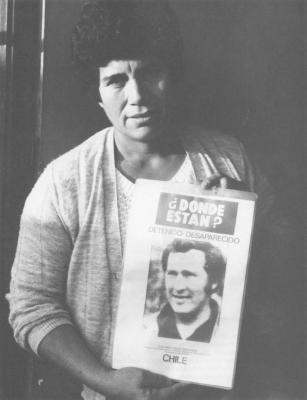

Between 1973 and 1977, the Supreme Court rejected all but one of more than 3,000 habeus corpus petitions filed on behalf of individuals--mostly leftist activists--who had been kidnapped by security forces or held incommunicado in clandestine prisons. At least 600 of these prisoners never reappeared.

In many cases, judges ignored overwhelming evidence in order to accept the official version of events. In the lumbermill town of Laja, where 19 prisoners disappeared after the coup, the investigating judge dismissed statements from dozens of relatives who had seen them in custody, and chose to believe police, who swore they had never been detained. In 1979, their bodies were found in a nearby cemetery, shot at close range.

Judges were especially reluctant to cross state intelligence agencies, which routinely refused to provide them with information about prisoners and referred them to the Interior Ministry. By obediently following this time-consuming paper trail, which often took weeks, the courts fulfilled their legal duty without provoking government wrath-while many prisoners were being tortured or even killed.

In theory, judges had the right to inspect police facilities at any time, but only a few ever attempted to do so. Supreme Court justices made periodic visits to detention camps but authorities generally knew in advance. Despite frequent reports of torture from other sources, the judges usually pronounced their tours satisfactory.

The issue of "disappeared" prisoners was an awkward one for Chile's justices, because of the international condemnation it brought upon Chile. But the Supreme Court repeatedly rejected requests by officials and lawyers of the Catholic Church to investigate the problem. By 1978, not one of 604 fully documented cases had been solved.

Over the years, a handful of lower-court judges vigorously pursued cases of human rights abuse, but their findings were always overruled. In 1985, when three Communist Party members were found beheaded, Judge Jose Canovas Robles undertook a painstaking investigation and charged 17 police intelligence agents and officials. The scandal led to the resignation of Police Commander Cesar Mendoza, but the Supreme Court freed all major defendants for lack of evidence.

One judge, 71-year-old Rene Garcia Villegas, not only challenged the secret police but spoke publicly against torture after taking statements from dozens of prisoners who described being subjected to electric shock and other abuse. In October of 1988, a tape of his comments was broadcast on television as part of a campaign to unseat Pinochet in a public referendum.

These actions earned the judge accolades from Chilean democratic leaders and human rights groups. But within Chile's judicial system, they were viewed quite differently. After a long and exemplary career, he was temporarily suspended from the bench at reduced pay, and permanently denied any chance for promotion.

"I always took my oath to provide justice very seriously, and when complaints of torture came to me, I had to do my duty," Garcia explained in an interview. Asked why he had received such opprobrium from his superiors, he sighed. "Military rule has provoked great conformity and fear. The courts don't want to offend the government. It is much easier to take the comfortable position, and that is what had happened for 16 years."

What explains the apparent transformation of Chile's judicial system from a proud defender of constitutional rights into a passive collaborator of military rule? Part of the answer stems from the courts' experience during the three years of socialist rule that preceded the 1973 military coup.

Many judges were conservative by nature, and they felt manipulated by the government of President Salvador Allende and humiliated by his followers. In contrast, the new military junta went out of its way to pay formal respect to the courts, pledging to respect their autonomy.

The Supreme Court was grateful for this dignified treatment. and responded by helping to imbue the regime with juridical legitimacy. In 1974, after the four-man military junta designated Pinochet "Supreme Chief of the Nation," Chief Justice Enrique Urrutia solemnly bestowed a new presidential sash on the general.

Many judges shared the regime's strong anti-Communist beliefs; they tended to regard leftists as enemies of the state. Some were made uneasy by the unsavory practices of the secret police, but many regarded its work as a necessary price for freeing Chile from communism. They suspected "missing" leftists were in hiding or that the charges were deliberately fabricated to discredit the government.

"When the prisoner is a communist, for many judges at some level he represents not a human being, but three years of Allende. The judge may be convinced he is being fair, but that prejudice often filters through in his treatment of the case," commented one appeals court judge.

The failure of Chile's courts to aggressively pursue charges of state abuse also stemmed from their training in the positivist European legal tradition, which emphasized literal application of the law and discouraged judicial activism. In moving up the career ladder, judges were rewarded for routine service and precise legal knowledge rather than creative thinking.

This emphasis on formality, which had served Chile well in democracy, became an excuse for inaction under military rule; a way to avoid clashes with formidable institutions like the secret police, whose power grew to be feared at all levels of society and government by the late 1970s.

Another tradition that reinforced conformity was the Supreme Court's absolute control over the judicial ranking and promotion system. Lower court judges who wanted to advance were wise to adopt the views of the elderly, mostly conservative high court justices, sticking to the letter of the law as strictly as possible.

The most outspoken conservative on the high court was Israel Borquez, who remarked after being named Supreme Court President, "'The disappeared are driving me crazy. I don't believe they exist." A provincial judge, receiving a petition to find and protect a missing local labor leader, would hardly feel encouraged to pursue the case with vigor.

From its first days in power, the Pinochet regime cleverly manipulated the judicial fetish for strict legality. Each of its actions, however harsh, was cloaked in a mantle of elaborate legal language, which made it easy for judges--and law-abiding citizens--to accept political repression.

Over the years, the regime issued hundreds of decree-laws, prepared by teams of legal aides and approved by the four-man military junta serving as Chile's "legislature." These laws, usually linked to the "states of emergency," permitted officials to censor news, hold prisoners incommunicado, banish dissidents to villages, and exercise a wide variety of other powers.

In especially controversial cases, officials made their decrees secret. In 1974, when the regime created a secret police agency called the National Directorate of Intelligence (DINA), secret provisions gave it powers to arrest, imprison, and demand cooperation from all other government institutions.

Military authorities often used the law to harass the few lawyers who were willing to help leftist victims of torture or repression, and here too the courts offered little resistance. In 1976, police agents seized two prominent human rights lawyers and within 90 minutes they were on a plane into exile. Vigorous protests were lodged by prominent citizens and church officials, to no avail.

The Supreme Court sought refuge in legal obfuscation and ruled in favor of the government, accepting its argument that the men were "dangerous to internal state security" and ruling that under existing emergency powers, officials did not have to produce any substantiating evidence.

This bitter experience, wrote Eugenio Velasco, one of the exiled lawyers, "made me lose all hope in the dignity and seriousness of the Supreme Court" and wonder whether "in Chile we were profoundly mistaken when we felt pride in our tradition of respect for the law."

In order to make sure it was legally protected against charges of human rights abuse, the regime decreed a law in April of 1978 granting amnesty to all "authors, accomplices or concealers" of political crimes since the coup, and Chile's higher courts enforced it with great firmness.

Officials said their motive was to promote "national reconciliation," and the law did free several hundred leftist prisoners. But its chief effect was to overturn hundreds of cases of abuse and disappearance. Crimes like the executions in Laja were simply wiped off the books. In 1988 a former member of the junta, Air Force General Gustavo Leigh, called the law a "barbarity" and said he never should have signed it.

The regime's most ambitious legal weapon, however, was the 1980 Constitution, by which Pinochet sought to legitimize de facto rule and change the very nature of relations among state powers. Amending the 1925 constitution was not enough: the regime wanted to create a new, authoritarian legal order.

The proposed charter banned any group advocating "class struggle," granted the president wide repressive powers and set out a slow transition to civilian rule. After a month of intense regime propaganda, a public referendum was held under strict military control and authorities announced the charter had been approved by 67 per cent of the voters.

It later became clear that many voters had little idea how much power the abstruse document conferred on the regime, and experts debated the meaning of many provisions for years. But once the constitution was approved, the courts had a complete, formal set of rules to obey instead of a patchwork of executive decrees and acts, and their technical conformity to military rule became that much easier.

Despite its strong domination over civilian courts, the Pinochet regime did not completely trust them, and turned to the military justice system as a mechanism of legalized repression over broad categories of political crimes.

After the coup, special Wartime Military Councils were set up to try leftists seized under the "state of siege." Prisoners were given little chance to prepare a defense, accusations of subversion were often based on anonymous tips, and sentences were extremely harsh. At least 200 people were sentenced to death and quickly executed.

The wartime councils were used rarely after 1975, but the scope of military courts, which served at the pleasure of the regime, continued to expand under a series of "state security" laws. The judges were military officers who tended to dismiss charges of abuse against government agents and impose harsh sentences on leftists charged with participating in revolutionary groups.

"These men are not impartial; they are fulfilling a military function. They are in a war against Marxism, and when you are judging your enemies, there is no way you can be impartial," charged Roberto Garreton, a leading human rights lawyer.

Although military court proceedings were secret, an occasional case shed light on how they functioned. In 1979, a science teacher named Federico Alvarez Santibanez was brought before a military judge after five days in secret police custody, badly beaten. Police presented a doctor's statement that he was in good health and the judge ordered him back to prison.

The next morning, Alvarez was rushed to a hospital and died. An investigating judge found he had received severe head injuries, but the case was closed by the military courts, which ruled that "there appear to be no founded presumptions that certain persons participated in said crime."

The use of military courts to prosecute revolutionary groups intensified after 1980, when the regime broadened state security laws so that virtually anyone linked to such a group could be charged under military codes. Military courts were even empowered to try anyone who "offended" the armed forces, including political cartoonists.

The military courts became especially rapacious under Col. Fernando Torres Silva, a prosecutor known for his persecution of leftists and his contempt for civilian courts. In 1988, a United Nations investigator charged Torres had converted military justice into "an odious and unjust instrument to repress" and intimidate, but Torres blamed all criticism on a leftist "campaign of misinformation."

Since the October 1988 referendum that unseated General Pinochet and paved the way for presidential elections this December, the reform of Chilean justice and laws has become an important battleground in the transition to democracy.

After arduous negotiations last spring, opposition leaders persuaded government officials to accept 54 reforms to the 1980 constitution, which were then overwhelmingly approved in a July 1989 referendum. The ban on groups advocating leftist doctrines was changed to a prohibition against parties that used political violence, and the power of the military-controlled National Security Council was reduced.

But a number of other legal problems lie ahead, especially in the area of human rights. Many regime opponents are determined to rescind the 1978 amnesty law so that military abuses can be prosecuted once a civilian government takes office in March. But high-ranking officers, fearful of mass persecution, have hinted they might intervene forcefully to prevent such a measure.

Many experts believe the entire judicial system is in dire need of reform, especially the lopsided balance of power between civilian and military courts. But the Pinochet government has moved swiftly to leave its permanent, conservative imprint, offering retirement bonuses to Supreme Court justices and naming nine new members to life terms in the past year.

German Hermosilla, a cautious reformer who heads the National Magistrates' Association, believes the most urgent need is to open stuffy courthouse windows and let in some new ideas. For several years, he has been hosting seminars on judicial ethics and professional standards, and each time a few more judges have attended.

"People were afraid at first. Judges like Garcia and Canovas were threatened, and you couldn't ask the others to be heroes," Hermosilla noted. "That's changing now, the taboos are falling, people's eyes are opening. We still have to be very discreet, but we hope that with democracy, we can begin to build a justice system that is truly modern efficient and independent."