Choosing Servility To Staff America's Trains

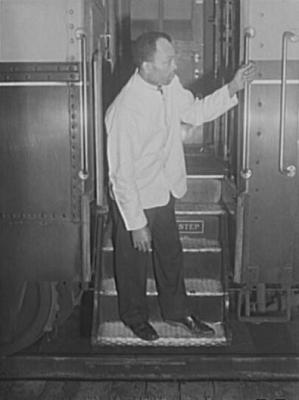

He was a black man in a white jacket and sable hat. He only recently had stepped out of the cotton fields, and now was stepping onto one of the locomotives that had symbolized freedom to slavehands like him. He lit the candles that illuminated the passenger carriage, stoked the pot-bellied Baker Heater, and made down the hinged berths that transformed a day coach into an overnight compartment. He was part chambermaid, part butler, shining shoes, nursing hangovers, tempering tempers and performing other tasks that won tips and made him indispensable to the wealthy white travelers who snapped their fingers in the air when they needed him. It was the only traveling he would ever do.

That much is known about the first porter to work on George M. Pullman's railroad sleeping cars. What is not known is his name, age, birthplace, date of employment, or just about anything else about him. Historians will say the reason for that is that a fire in Chicago destroyed the early archives of the Pullman Company. But, curiously, it didn't destroy the names of the first two primitive Pullman cars, remodeled day coaches 9 and 19 of the Chicago, Alton & St. Louis Railroad, or the names of the first three paying passengers, all from Bloomington, Illinois. Or even the name of the original conductor, Jonathan L. Barnes, whose life story is preserved in infinite detail.

The first porter, in fact, was not expected to have human proportions, certainly none worthy of documenting. He was a phantom assistant who did not merit the dignity of a name or identity of any sort. That is precisely why George Pullman hired him. This new improved porter was an ex-slave who embodied servility more than humanity, an ever-obliging manservant with an ever-present smile who was there when a jacket needed dusting or a child tending or a beverage refreshing. Few inquired where he came from or wanted to hear about his struggle. In his very anonymity lay his value.

And so it was that the polished passengers who rode the plush velvet-appointed night coaches over the first half-century of Pullman Palace Car service summoned him with a simple "porter." The less polite hailed him with "boy" or, more often, "George." The latter appellation was born in the practice of slaves being named after slavemasters, or in this case porters being seen as servants of George Pullman. It stuck because it was repeated almost instinctively by successive generations of passengers, especially those below the Mason-Dixon line, and by journalists. The only ones who protested, at least at first, were other men named George. They were sufficiently upset with the perceived slight that they founded the Society for the Prevention of Calling Sleeping Car Porters George, or SPCSCPG, which eventually claimed 31,000 members including King George V, George Herman "Babe" Ruth, and France's George Clemenceau.

Porters, meanwhile, were moved to concoct mythic forefathers in their bid to lay claim to a heritage. Characters like Daddy Joe, a Bunyanesque figure tall enough to pull down upper berths on either side of the aisle at the same time, agile enough to make down the uppers and lowers simultaneously, eloquent enough to talk a band of marauding Redskins into accepting a pile of Pullman blankets in place of passenger scalps, and so appreciated by his riders that his pockets were weighed down with silver and gold. Daddy Joe may or may not have been real, but his stories were retold often enough that he surely reflected porters' aspirations as well as their itch to be acknowledged.

Whether George Pullman ever heard of Daddy Joe, or even knew his passengers were calling his porters "George," is uncertain. What is clear is that the gray-bearded entrepreneur from upstate New York was a titan of timing and a prince of publicity even if he wasn't quite the ingeneous inventor that history has crowned him. The Civil War was just ending when Pullman rolled out the most elegant sleeping car he or anyone else had ever designed, appropriately dubbed the Pioneer. Pullman understood that railroads would soon link the urban East Coast with the newly settled West. He knew that passengers on such longer runs were tiring of sitting up all night, or trying to sleep in beds so hard that passengers labeled the experience a waking nightmare and so soiled that men kept their boots on and women never considered climbing in. And he realized that, if travelers could try for themselves his spacious new surroundings, lucious linen and bedding, and smooth-riding paper wheels they would line up to lay out the extra 50 cents for a berth on the Pioneer.

Luck, and the Lincolns, created his opportunity. In order to fit its spacious sleeping quarters the Pioneer had been built to dimensions too high and wide to fit under platforms and onto bridges used by railroads of the day. But after President Lincoln's assassination his widow Mary Todd, who had collapsed of exhaustion on the train trip from Washington to Chicago, asked that the Pioneer be attached to the funeral cortege for its final leg to Springfield, Illinois. George delightedly obliged, in the process helping boost his new sleeper in two ways. Workmen labored night and day to raise platforms and widen bridges so the Pioneer could pass. And the publicity surrounding its last-minute addition to the funeral procession ensured that all of America got word, creating a groundswell of demand for the grand new night train and pushing railroad executives nationwide into making whatever changes were needed to handle it.

Now that railroads were anxious to pull his sleepers, and passengers were willing to pay, George knew he had to offer the kind of accommodations that would keep both coming back. His models were the finest hostelries and eateries of the day, and he saw that the appeal of both began with their flawless service. But how to bring such service to his novel Hotel on Wheels? Again, President Lincoln pointed the way. Just two years before he had signed the Emancipation Proclamation that created a labor pool of more than 3 million ex-slaves. Legend has it that Lincoln suggested to Pullman that he hire the freed Negroes for his sleepers, but George probably didn't need any pushing. Former house servants were his porter of choice, given their experience in tending to white masters, and the darker-skinned the better to reinforce their otherness. Most came from Alabama and South Carolina, the Old South states where the labor pool seemed biggest and cheapest. And, from the very start, porters not only starred in George's ads promoting his new sleeper service but were one of the features that most clearly distinguished his carriages from those of competitors (although nearly all would eventually follow his lead, hiring Negroes as porter and cooks, waiters and Red Caps).

Pullman went on to become the biggest single employer of blacks in America, and the job of Pullman porter was, for most of the 101-year history of the Pullman Company, one of the very best a black man could aspire to, in status and eventually in pay. The porter reigned supreme on George's sleeper cars. But the very definition of their jobs, of their kingdom, roiled in contradictions. The porter was servant as well as host. He had the best job in his community and the worst on the train. He could be trusted with his white passengers' children and their safety, but only for the five days of a cross-country trip. He shared his riders' most private moments but, to most, remained an enigma if not an enemy.

George never talked much about how he felt about Negroes, or why he chose freed slaves as porters. But he also never wavered from the practice. Nor did his successor as president of the Pullman Company, Robert Todd Lincoln, son of the Great Emancipator. It was during the young Lincoln's tenure as chairman that Pullman officials were called before a congressionally chartered commission and questioned about their hiring policies. L.S. Hungerford, the general manager, explained that "the old southern colored man makes the best porter on the car." Asked by the commission chairman why, Hungerford recounted a philosophy that George had made into a mantra decades before: "He is more adapted to waiting on the passengers and gives them better attention and has a better manner." As for where the company recruits them, Hungerford added, "We get mostly house servants."