New Burlington, Ohio: When A Town Dies - The Coming of Machinery

New Burlington, Ohio: When A Town Dies

The Coming Of Machinery

The Coming Of Machinery - I

One must work, if not from taste then at least from despair. For to reduce everything to a single truth: work is less boring than pleasure.

– Baudelaire

It is said that the farmer’s best years were from 1910 until 1914. Those were the good years, when a precarious kind of symmetry existed. The farmer made 70 percent of what the urban worker made in those early four years of this green century. Soon after, he began to fall even further behind. And the alchemists of a new age reasoned accurately that the basic elements could be converted to gold. In nearby Dayton, even as the good Bishop Wright thundered blasphemy to such dreamers, his own blood betrayed him: his sons conquered gravity in a dusty bicycle shop, thereby promising the moon to men in their time. The agent of such thaumaturgy would be capitalism, a steel-ribbed hunk of a word the nation movers could use to prove themselves, like the disciplined circumstance of geometry where an entire cosmos is built upon the acceptance of a theorem none can prove, but all accept. It was a word of sharp angles. It rattled across the tongue. It was a heavy blunt instrument of a word to bludgeon a reluctant age into manageable shape, like its companion word – machinery. They were hard, practical words, never to be used in poems or hymns. Those practical words would supplant such fragile events as poems and hymns. A new rhythm had already begun its immutable metallic drone. A new hope stirred in the promise of this clumsy century.

The Coming Of Machinery - II

In the difficult fields, the farmer looked at the ill-conceived shapes of the new technology and turned reassuringly to his horses. The sweaty flanks moving under leather harnass compelled him. He would not yet turn away from the muscle and blood pulling him through the furrows. He felt wedded to it. Perhaps such feelings came from stubbornness. The fields taught that well. He was uncertain, and since he was uncertain, it meant he would change. But not for the moment. At night, under a raw sky, his wife heard him come to bed. She subconsciously prepared herself for his weight in the bed, which made her shift in half-sleep. He breathed deeply out, a sound which carried a subtle tone. She thought sometimes it was resignation, a breath at the end of all breathing, to either stop, or to begin anew. And so it frightened her, even in this twilight of sleep, and she moved until she felt his rough hand upon her hip. His breathing began again, the quiet orderly rise and fall before sleep. She relaxed then (such easy wisdom) and was content for a long moment, and such contentment provoked a minor resentment. She resented his hand. She resented it all. She slept, and sleeping, she dreamed of herself in harness, like the old etchings reproduced in history books, bent women dragging a plowstock through uneven fields.

The Coming Of Machinery - III

Everett Mendenhall farmed the bottomlands across Anderson’s Fork from Frank Lundy. He was the first of his neighborhood to buy a tractor. Afterward, his brother-in-law referred to him in company as ‘one of those…tractor farmers.’ Under the laughter that followed, Everett Mendenhall felt a cutting edge. He felt suddenly apart from his neighbors, as if he had a diseased herd, or left his corn rows to summer crabgrass, or mistreated his horses. He felt guilty. As the tiny Farmall F-12 dug into the earth, the noise echoing across the creek, he felt high above the ground, and exposed. He could see Roy Reeves plowing with his team below the covered bridge. He wished the tractor were quieter.

To the east, Albert McKay bought an Allis-Chalmers but he left it to his four boys. “What you can’t do with horses,” he said to his neighbors, “isn’t worth doing anyway. I scorn the damned thing.” Seasons later, standing in a barnyard empty of all but his tractor, Albert McKay climbed hesitantly on and headed for his fields. He remained there for 12 hours.

To the west, Luther Haines and his father, Zimri – named after his grandfather who was named after a minor prophet – bought a Fordson and a three-bottom plow in 1919. It cost them $900. Being a ninth-generation Quaker, Luther Haines had good conservative instincts to guide him in the new economics. He did not like the machinery but he respected it. He thought the change was too expensive. Nine hundred dollars. The entire Revolutionary War land grant tract his farm sat in the middle of, the whole one thousand acres of it, did not once sell for anymore than he had paid for one tractor and a plow. He wondered to himself what this would mean. It made him feel uneasy. He remembered what Zimri told him more than once before he had married: ‘You need three store-bought things. Salt, sugar, a little kerosene. Cut wood. Butcher. Trade extra lard for the sugar. Trade wheat for flour. Be independent.’ He felt things slipping away from him. He remembered Zimri once borrowing money from a neighbor, who went to the staircase and took $300 from under the carpet. He continued to use his horses in the fields until he got behind, then he used the tractor. A man has to compete, he thought behind the horses. But he sensed betrayal.

To the southeast, Volcah Hackney gave himself a hernia trying to crank his new tractor. It bothered him the rest of his life. His neighbor, Everett Early, got one the same way. On rare occasions when they met in the village, noticing the other’s gingerly steps, they smiled sheepishly at each other.

The Coming Of Machinery - IV

The machinery crept into the fields, over the roads, and into the houses. Young men learned to drive the Model T in the nonprohibitive wideness of the barnyards, so they would not hit anything. Dread scattered livestock to far fence corners. Jack Skimmings headed from New Burlington to Wilmington in a phaeton buggy pulled by a sway-backed mare. On the graveyard hill, he met a man on a motorbike. The mare stopped to watch as the motorbike came closer. Then she took the bit in her mouth, turned around, stuck her tail into the air and ran Mr. Skimmings back into his barn. His wife watched from the porch. “Why, Jack,” she said, “I thought you were headed to Wilmington.”

“Well, yes,” he replied, “I was headed to Wilmington but I met a fellow on one of those farting bicycles and the old mare brought me home….”

Howard Pickering, the blacksmith, drove his father in his Model T while the elder Mr. Pickering, himself a fourth generation blacksmith, held his door open, ready to leap into the fields at the slightest provocation. Rose Devoe, the seamstress’ daughter, could never remember to use the brake. She pulled back on the steering wheel and yelled for the motor to stop. When Irving Blair, the groceryman, bought a refrigerator for his family, his mother called him frivolous. “We have a cellar, Irving,” she said. “What is wrong with the cellar. Cold, fat stone. A refrigerator is so…unnecessary.” The elder Mrs. Blair, however, was outvoted. The refrigerator was brought into the house, where it retained a place of honor in the living room. Soon, Sarah Shidaker, now a farm wife, had a deep freeze, bought with the milk money. She took a long look at its gleaming porcelain expanse and said, “Why, if I should die, my Eddie could lay me out in here and keep me forever!” Sarah Shidaker accurately set the new faith: “We were once in no big hurry. But no one wants to return to a team to turn a furrow. We have a tractor that turns three furrows. We milked “armstrong” at first, now we have milkers, two at a time. A housewife would rather have a Mixmaster than a crock and a spoon. But there was something warm in the old ways that I no longer have. So many people work strange ways and there are no more Sundays and no more nights. Now, I wonder what is important, and where will my grandchildren have their potato patches…?”

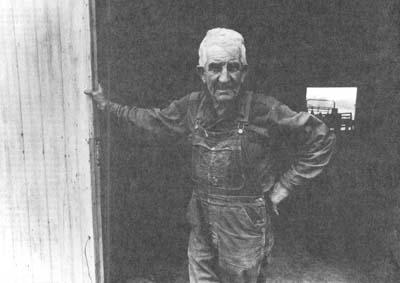

I have always known farming. It is what I began with and I’m still at it. I like it because it was how I was raised. I think it is where a man is born. My father stayed with it until he was 85. We worked by hand and horse and walking plow. I don’t like to talk of it because it makes me seem old.

– Thurmond Mitchner

When we got behind we used the tractor. We thought the tractor was wonderful but the horses we thought sacred. The teams did a lot of thinking for a man in the fields. The horse turned and went down the right row. There was a closeness there. The tractor gave us nothing. But the machinery was coming on, you know….

– Luther Haines

I didn’t like shearing a sheep. It was too far from his head to his feet.

– Albert McKay

The Coming Of Machinery - V

Years later, one night in late July, when Frank Lundy’s cornfields shined richly under a full moon, one of the village boys raced his new Chevrolet the quarter of a mile from Burlington to the cemetery while his best friend stood on the running board and sent a mighty stream of urine into the field. It was one of the minor eccentric moments in a young man’s life when he is given to such fine spontaniety. But who could say that it was not the perfect gesture of defiance to the confining fields? The factory system awaited. The automobile awaited. All roads led to Rome. At the moment of such coalescence, New Burlington, Ohio, ceased to exist. The fields, passive under the inexorable grind of relentless seasons, gave no promises. The cities promised everything.