New Burlington, Ohio: When A Town Dies - Summer

New Burlington, Ohio: When A Town Dies - Summer

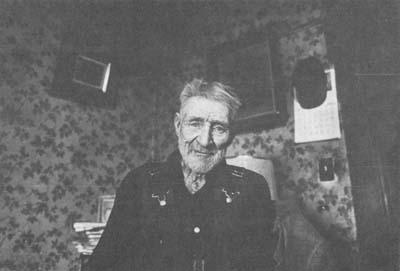

It is an ordinary chair, of good mahogany and quiet cloth. In front of the rockers, the figured carpet is worn, an acquiescence to Mrs. Louie Wills’ passage through the seasons. The chair is the center of her existence, as if the rockers themselves absorb grief, loneliness, and age. From the chair, everything is equidistant: kitchen, bedroom, television, front porch and neighbors, even the minister of the Nazarene Church around the corner, whose bleak wrath in the warm months when windows are flung up bludgeons the center of the village like failure itself.

Louie Wills’ skin is like fine parchment; her hair the shape and color of the clean alabaster curl of a conch shell. She has been allowed that greatest of gifts, to grow old with grace. At 95, she hears and sees well and lives alone, taking care of herself and a one-eared cat which comes to the door and whispers curiously, like a rasp against soft metal, to be let in. If Louie Wills is not surrounded by self-knowledge, she has been given serenity. It cannot be said of her that she could not, at least for a time, dwell alone in a quiet room.

Like the chair being the center of her existence, she is the center of the town’s existence. Known, familiar, representative, all lives and the course of events pass this way. Mrs. Louie Wills is rural ritual, part of the quiet process of elemental disintegration which begins with the separation and movement of family and ends years later in death itself.

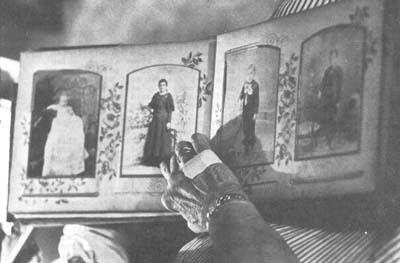

Like most of the widows who live in New Burlington – among them her 85-year-old sister, Abby Curry – Mrs. Louie grew up as the daughter of a farmer, then married a farmer. “There was 10 of us and we was for each other, I remember that. We made our own clothes and raised our own feed and after my mother died young, my little brother stood on a chair to mix our bread. Before I was a grown lady, we lived four or five years around Port Williams and that was the way things was. I was 31 before I got married and nobody thought anything about it. I met Frank at the Rebecca Lodge. He was a school teacher down in Pike County and had a sister in Port Williams. He came up in the summer and helped run the threshing machines. I never went much with anybody else because I thought I had to like ‘em well enough to marry ‘em. I thought from the first he was a mighty nice looking fellow. My grandmother said to my father, ‘Si, if I was you, I’d take a shotgun to that buck,’ but my father wasn’t my grandmother, and Frank and I were married in 1907. She thought it would be bad to leave my father but we took care of him. Whenever he took sick, we would be there. He was 94 when he died.”

Frank and Louie Wills got their farm three years after they were married, 125 acres on the side of the valley just east of New Burlington, the houses and barns grouped tightly together under the brow of a hill beside a country lane, small and neat and carrying a certain accurate perspective of ambition, not so small as to be pretentious, like the gentleman farmer visiting his fields on weekend outings, nor so large as to lose an intimacy with it. Frank did not like being a school teacher, it confined a man. The summers in the fields of Port Williams, the sun baking out of him the sums and equations of a winter in the classroom, gave him new prospects. The fields compelled him, became an observatory from which he judged the constellations of his own existence. The farm was rough land, what he called a “pasture farm.” They dug a cave for the fruit and vegetables. Frank worked the fields with horses; he felt comfortable with horses. They brought up full-blooded Herefords, pigs, and two children. The land surrounded them, absorbed their work, made them self-contained. They lived less than a half-mile from the village of New Burlington, yet it appeared as remote as an ocean. They spoke of it as though it were of a life separate, unknown to them, and distant. Frank recognized, when his son told him he did not want to farm, that distance had been deceptive. A great sadness came to him. The land was not insular, or self- sustaining. The enduring rhythms were broken. The only thing Frank Wills knew was that his son would not inherit. Inherit what? the voices whispered, but no thoughts came his way, no quickening rage, only the first process of disintegration.

The illnesses were next, first to Frank, and much later to Louie, over 15 years later, after the engineers came, and who was to say about the nature of the thing under the surgeon’s knife? Mrs. Louie went to the hospital the summer she was 95, the summer she was to move again. Was it a recalled primal memory that whispered of how the sick soul bent the body? Did dim and ancestral introspection crowd at night the stained walls of the mind? disease always meant different things in the country. When it occured, the victim was jostled against the framework of his own bones. It was his illness, he grappled with it in his own isolation, and help was far away if at all. It was where the predator and the prey met in some dank and alien corridor and stared at each other across a space until one, averting at last an uncompromising gaze, slinked away. He thought one night, racked with fever, that he was smothering in animal skins and where the night-light was, an older light wavered, throwing dull yellow shadows through a doorway that lost its shape into a blackness deeper than any he had ever known. Why was the talk of country folk always of disease, not of health? Why was the course of events plotted by the stethoscope? The healthy villagers were not the stuff of gossip, it was the fallen, and the talk was not of the man or woman under the shadow, but the very disease itself, as if they suffered from a visitation which had a life all its own and they were held in unseen combat like armies of light and dark. The hands of condolence touched him like the flutter of winter birds. The solicitude, shrill at the edges like the point where laughter joins hysteria, flung him to terror.

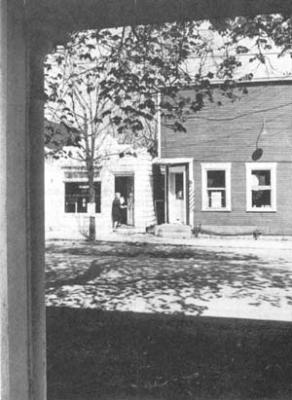

Frank died of cancer eight months after he and Louie moved into New Burlington. In 1956, he had known that he was both too old and too ill to farm anymore, as if one was a symptom of the other. The red-shingled house had been small but adequate. The grocery store was across the street, the post office was perhaps thirty yards farther in case any of the grandchildren wrote from California or wherever it was now, and Louie’s sister was just up the street. Life and disease and death itself, each paralleled the other, except New Burlington was a village where the pendulum was weighted, where the people were as old as the village. Illness struck the farm, death struck the town. A somber partnership was cast. Those who were ill moved into a house left vacant by death. In the last decade of New Burlington’s life, only one new home was built, a brick-veneer ranch house beside the Methodist Church, as incongrous with the double-storied frame homes across the street as an unknowing tourist is cannibal to quiet custom.

Mrs. Louie had her home, her sister from whom she had never been separated, her neighbors were solicitous, and her daughter lived only a few miles away. She had lost her husband but not her centrality, rather, if anything, she had gained more, because she had become a widow. The other villagers, particularly the women, were kind to widows, as if by paying court to widowhood, it would keep the rough beast away from one’s own doorpost. The village had many widows. Mrs. Wills’ sister, Abby, lived in the middle of six of them, a wide sorority of imposed spinsterhood. When the engineers came, the sorority suffered perhaps more than most because they had made of themselves another community, a complement to both family and village. Now they would have to pay for being so social, for after all, the engineers, those olive-drab pipers, would not pay for such a minor disruption, if, indeed, they ever paid for the evisceration of community in any form. By the time the bidding began, three widows were left around Mrs. Abby. One had died, one had moved away. Of those left, one refused to go (of course she would go, they all would, but such thoughts served to tuck the reality of it away in some small attic room of the mind) and another asked that she be allowed to die before she had to move. She prayed to God for the grace of death. She even tried to will herself into death, as if caught for a strange moment in some stark atavism worked by her centuries-old ancestors who still possessed an ear sharp enough to hear the final collapse of cells within the body. None of this happened, however, and in the summer, the sorority got together for a final time. They put their belongings together and sold them. After the family had picked through the houses like first guests at a well-laid buffet, the outsiders came. They had been circling about New Burlington longer than rumor, wheeling in tightening arcs, sniffing failure. The widows went away after that, to the side rooms of their daughters, one to a trailer park in Spring Valley, Mrs. Abby, finally, to a rest home in Columbus. Before she left, she called the veterinarian from Spring Valley who put her cat to sleep while she held it in her pale arms.

Like most of the grief in New Burlington, Mrs. Louie bore it silently, and that was both virtue and villainy. She stayed in more, and she had stopped going to the Methodist Church next door to Abby. She said she couldn’t stand to be in a crowd. Most Sundays, she sat on her porch and listened to the Nazarene minister cover the land with imprecation. “He gets pretty high, I tell you,” she said, laughing her soprano laugh which after all those years still carried the edge of a schoolgirl’s blush. Her daughter teased her about the “porch news,” because Louie’s neighbors often came to sit with her on the small stoop. Mrs. Louie continued to do her own mending, but she didn’t attempt making quilts anymore, and so she had lost her craft. The quilts were made from old clothes and after Mrs. Louie had made over 200 of them, Frank told her that he was afraid to go to bed because his clothes might end up in a quilt overnight.

Just after her last birthday (she was as ancient as papyrus), she moved back into the country to live with her daughter, and the timber was torn away from her house. They were empty then, or gone – Mrs. Wills’ house, and the old store next door used for an apartment building, and the house across the street, all desolate as madness. Only Mrs. Louie’s front chimney remained, still shrouded in ivy although someone had clipped it off near the ground, taking the roots and leaving the waxy tendrils to wither away. Mrs. Wills did not notice which things remained unchanged and which things did not, either in New Burlington or in the country she could only partially belong to. She did not look back, neither did she wish to. She spent her life on the farm, living only a few years in the village, and now she was back in the country and if the rooms seemed smaller and the walls narrow and pastel, if the driveway was asphalt and the siding aluminum, why, the sky was still wide and the garden out back and in two months the asparagus would be tender for picking. She did not notice the walls of the rooms of her life, and if by dislodging her the Army Corps of Engineers had done anything to her, it was that they had…inconvenienced her.