Tatlin (Who?!) At The Moderna Museet

Tatlin (Who?!) At The Moderna Museet

September 10, 1968

S. K. Oberbeck

Mr. Oberbeck is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from Newsweek, Inc. This article may be published, with credit to S. K. Oberbeck and the Alicia Patterson Fund.

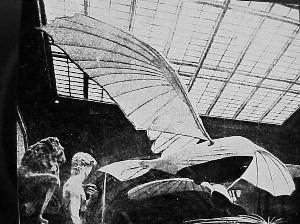

Tatlin’s Tower model – Dreaming Art in Wood vs. Making Agitprop in Iron

Stockholm—An art museum is much more, of course, than the naked eye can see. Stockholm’s Moderna Museet is almost hidden from the casual tourist’s view. Secluded on a pine-studded island across the water from the imposing Royal Palace and steeply cobbled Old City streets, the 10-year-old museum’s unprepossessing mustard-colored building is reached by a bridge at the end of a wide quay, along which stand the gilt-fronted Grand Hotel and the stately National Museum. But however out of sight the Moderna Museet may be for the art enthusiast in Europe, it can never be far out of mind.

In a scant decade, the museum and its director, K. G. P. Hulten, have earned an international reputation for progressive and effective exhibitions and activities. These have included a comprehensive kinetic “light and movement” show in 1961, a program of multi-media “New York Evenings” (which inspired the subsequent “Nine Evenings” in Manhattan), a show entitled “The Inner and Outer Space” featuring such artists as Naum Gabo and Kasimir Malevich, and a much-heralded sculpture-architecture happening called “She” in 1966. When, later this fall, Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art opens its show called “The Machine” (with a flossy, metal-covered catalogue), it will be the product of Pontus Hulten’s direction.

After-Five Crowd

As much as, if not more than, any other museum of comparable size in Europe, Hulten’s Moderna Museet has consistently been breasting the artistic tape with front-running exhibits and events. A bit of background on Hulten’s singular creation: though the museum opened in 1958 in the refurbished building formerly used as a drill center by the Navy, a pivotal date in MM history was 1963, when Hulten organized a huge, comprehensive exhibit entitled “The Museum of Our Wishes” that ran from conventional to ultra-current. The Swedish government afterwards granted the museum about $1 million kroner to start a public collection. Hulten estimates now about 3000 works grace the MM collection. He operates on a budget of some $60,000 a year; salaries are paid by the government. The galleries had 225,000 visitors last year, but have logged as many as 300,000 in a year. The “light and movement” kinetic show, says Hulten, pulled in 100,000 visitors alone. One distinguishing feature of the MM is that it stays open at until 10 p.m., an innovation Hulten feels fully justifies the extra costs (around $20,000): almost half of July’s attendance was comprised of the after-five crowd, whose median age Hulten judges to be 27.

At 43, Hulten looks about as much like a museum director as Trudeau looks like a Prime Minister. His style is casual and he inclines his graying, crew-cut head with the air of a careful listener, frequently grinning to punctuate a point. Commenting on the museum’s tight-little-island location (the Museum of Architecture and Academy of Arts are also there), he remarked that while the site was enormously comfortable and quiet, he also worries that “we may have too many comforts” and says he contemplates moving the museum smack dab in the middle of Stockholm’s busy metropolis. A possible location could be in the seat of Swedish government: a parliamentary change from a two- to a one-chamber system may provide the space. Toying with the notion of a moving day, Hulten remembered that when the MM opened in ‘58, it was in the midst of the debris of renovation, highlighted by the presence of Picasso’s “Guernica” which the Museum of Modern Art had lent from New York. Hulten dwells fondly on that birthday atmosphere of creative clutter.

But the baby has outgrown its cradle in ten years; the MM seems conspicuously short of wall space and there are not enough large rooms to contain the kind of artistic activity Hulten envisions.

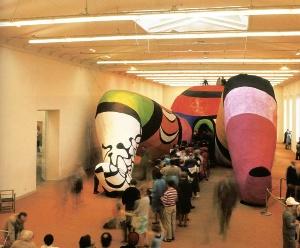

Niki de St. Phalle's Walk-in Nana “She” – Zany Celebration of Birth & Creativity

Compared to the bulk of the event-structure called “She” (a supine St. Phalle “nana” some 80 feet long), last month’s exhibit at the MM was prudently pint-sized: a 20-foot high model of a “tower” which highlights a retrospective show of works by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), the Russian Constructivist who with Gabo, Malevich, Antoine Pevsner and El Lissitsky founded the art movement whose influence is strongly effervescent among today’s modern artists. Along with reconstructions of Tatlin’s “reliefs” (which incorporate a variety of then-provocative materials) and photographs and paintings, the wood model is as faithful a reproduction as possible of the one Tatlin displayed in 1920 as the design for a monument celebrating the Soviets’ Third International. Hulten calls it “a very big work in a very small show.” The reconstruction was necessary (and the difficulties integral to the exhibit) because the Russians were loath to lend any of Tatlin’s work. Thus, the “reliefs” are facsimiles on loan from England, while Swedish artists collaborated on the tower model after studying existing photographs of the work.

Iron & Initiatives

Tatlin’s remarkable tower was a proposal to match the euphoric promise of the Communist revolution: a leviathan structure of spiral volutions, arches and geometricized girders that was intended to loom 400 meters high above the Neva river. Inside its gigantic, canted iron skeleton, gargantuan forms (two cylinders, a pyramid and a hemisphere) were to have revolved, making daily, weekly and monthly “revolutions” in reverent metaphor. It was to be the world’s highest structure (the Eiffel Tower is 300 meters tall) and its skin and bones—glass and iron—were considered the epoch’s logical modernist counterpart to classicist marble. It represented, true to the exigencies of the social revolution, a new synthesis of art, architecture and social purpose and reflected the basic aesthetic ingredients of the newly manifestoed “Constructivist” credo. Of course, the tower was never built; but, argues Hultgen, “Tatlin’s work is important more by the initiatives he took than by the actual projects he realized.” Tatlin’s dream ran into the wall of Soviet realpolitk.

The story of Tatlin’s audacious monument might be said to have begun when he visited Paris in 1913 and saw Pablo Picasso’s radical new cubist reliefs. These (the recent Picasso show at MOMA in Manhattan included some) depicted musical instruments and still lifes, but in a style employing actual pieces of wood, tin, wire, string, paper and other “found” or painted materials. To Tatlin, this mixture of eclectic materials and their description of a third dimension proved a revelation. He returned to Russia and began making his own “reliefs” out of wood, metal, glass, stucco—scandalizing Russian critics who were quick to find degenerate qualities in this upstart’s creations. In a typically Soviet example of the positive-defense, Tatlin countered accusations of negativism by labeling himself a “constructivist”—a double-barreled neologism that implied “constructivism” was faithfully dedicated to utilitarian socialist principles at the same time it described the central aspects of what quickly grew into an art movement.

The Medium Was the Message

The primary characteristics of Tatlin’s new formalism were its adherents’ devotion (at times, almost mystical) to the intrinsic qualities of the materials with which they worked and the notion that these inherent properties could determine the form—and even the technique of execution—of an artwork. The Constructivists articulated as well the import of space as a sculptural element (and artistic concept) as opposed to the traditional mass primacy of stone or bronze. They encapsulated their main preoccupations in the words “materials, volume, construction,” and “movement, tension...mutual relationship.” But even more importantly, in their revolutionary brand of formal abstraction, they asserted that an artwork’s content was implicit in the form and inseparable from it. Where the Cubists abstracted bottles, pipes and playing cards, the Constructivists broke with formal reality and began to use the actual materials in a new form that expressed a new content. For them especially, the medium was the message.

“The theory behind Tatlin’s Constructivism,” says Hulten, is that a rational construction, a logical structure based on the properties of the material...is the content; and this applies in art and in the revolutionary society.” Obviously, Tatlin was under constraints to ally his new art form to the precepts dominating the evolving Soviet state, to satisfy the requirements of revolutionary idealism and positivism. He declared that Constructivism was an organic product, or outgrowth, of the mechanistic era and that its relationship to architecture qualified it as socially useful.

New World Symphony

Remarking on the experiments he and his followers had been conducting, he wrote in 1920 that the results “are models which stimulate us to inventions in our work of creating a new world, and which call upon the producer to exercise control over the form encountered in our new everyday life.” A brave new world, in art at least, was by no means confined to revolutionary Russia. The Cubists, most notably Picasso, had already evolved collage techniques rendering their creations three dimensional. Boccioni, Severini, Ballà and their fellow Futurists, in turn, were discovering the visual kinetics of simultaneous points of view in sculpture and painting, and were conducting a love affair with speed, energy, and the machine no less ardent than the Russians who celebrated industrial promise of Marxist-Leninist revolution.

The whole of Europe was in artistic ferment. Not only had the two-dimensional pictorial surface been effectively shattered, but Duchamp and the Dadaists were also challenging other traditional concepts of form and content. Duchamps’ “readymades”—his famous bicycle wheel mounted on a stool and his bottle-dryer—were contemporary with Tatlin’s reliefs and later contre-reliefs. While the Dadaists, with their acerb hijinks, represented a movement of aesthetic criticism as much as a movement of art, they were no less serious in their aims than the Cubists, Futurists or Constructivists. The atmosphere of seriousness, of concentration, of “research” is worth noting in light of today’s artistic trends and in relation to the broad subject of art and technology—for the Russians, a major emphasis in their daily creative lives. “During the epoch of reconstruction,” proclaimed Stalin, “technology determines everything.” Tatlin got the message. So did some of his fellow Constructivists. Gabo and Pevsner got out of Russia.

Mystical Mastery

But Tatlin and others stayed on, trying to develop their aesthetic experiments while at the same time trying to satisfy revolutionary officialdom. El Lissitsky’s account of the building of Tatlin’s tower model gives some indication of the ideological line that had to be hewn by his fellow dabblers in the thin air of pure abstraction and subjective feelings: “In building up the object,” he wrote, “the starting point was the material used on any given occasion. The leader of this movement (Tatlin) assumed that the intuitive artistic mastery of materials leads to inventions on the basis of which it is possible to build up objects, independently of the rational scientific methods of technology. He thought he could prove this in his projected monument for the Third International. This work he executed without any particular technological knowledge of construction or statics, and thus demonstrated the truth of his belief. This was one of the first attempts to create a synthesis between the ‘technological’ and the ‘artistic’. The whole effort of the new art of building to open the volume, and to create a spatial diffusion at once from without and within, is reflected in this early work.”

Words & Deeds

To be accurate, Tatlin “executed” his project in a series of wooden models built on a one to ten scale. He and his helpers used laths and veneers to realize his monument’s soaring volutions and arches, fastening the laths together with brackets cut from tin. The project assumes a touching aspect of sheer bravado when one thinks of the primacy-of-materials notions invoked by the Constructivists. One wonders just what sort of mastery, or intimacy (without a knowledge of construction or statics) Tatlin possessed in regard to the iron, glass and concrete that were to comprise his behemoth of 400 meters high? But it must remain a matter of “initiatives” over “realizations,” which is not without a peculiar relevancy given the vaunted promise of revolutionary Russia and its grinding, actual history.

The 1920s were not the best of times for practicing artists; materials were in short supply. Theory and idealism often served as simulacra to the men of the Third International who set out to reconstruct the world. One dreamed in iron and realized in wood or paper. A small boy turned a crank to revolve the interior forms of Tatlin’s tower model when first it was unveiled. But even a wooden tower assumed transcendent proportions for most commentators who remarked positively on Tatlin’s sweeping proposal. Ilya Ehrenburg, one intellectual propagandist who (to steal from Kipling) became adept at keeping his head while all around him others were losing theirs, wrote in 1922: “It was all very moving. Soviet office workers were moving off with their rations of horsemeat . A boy was selling cake crumbs, and in the middle of the square, where once in the ‘civilized’ age had been an incipient garden, I stood with two artists, giving our fantasy free rein on the subject of metal. The cold led us to stamp our feet on the spot, and gesticulate like excited southerners. We were absorbed in our fantasy after making the acquaintance of Tatlin’s project for a monument to the Third International, and we had every reason to be absorbed.”

“For a self-taught white-eyebrowed prophet (resembling an artisan) had placed on the ruins of imperial St. Petersburg a clear sign, the beginning of a new architecture.” In the subsequent shuffle of history, however, the clear sign became somehow confused, and a different kind of monolith—cold, ruthless, despotic--dominated Soviet geography. And this is perhaps why Tatlin’s revival is touching and timely.

East to West

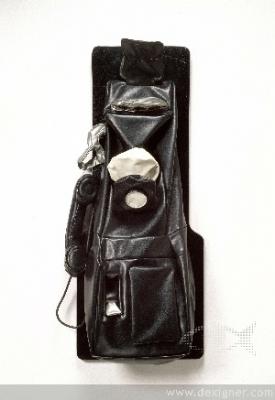

It is also perhaps ironic that the flower of Tatlin’s ideas and designs should have blossomed in the West rather than the East. Says Hulten: “Malevich and Tatlin and their ideas mean more at present for many of the younger artists than Picasso or the Surrealists.” And he adds: “I have the feeling that they will long retain a great influence.” That influence, sparked in part by Hulten’s predilection, is variously visible at the Moderna Museet’s galleries hung with today’s modern art. Three that are on the same floor an the current exhibit’s Tatlin tower: one of Swiss kineticist Jean Tinguely’s “Metamechanique” creations, a spidery construction of black metal tubing, pullies, motors and wheels which daubs out a continuous drawing as it wanders randomly around the floor. Pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s canvas study “Soft Medicine Chest,” a fabric mockup for a work done in shiny, pastel vinyl which is part of an entire “soft” bathroom (including commode and sink) complex that the whimsical Swede exhibited at Manhattan’s Sidney Janis Gallery; and poly-aesthete Robert Rauschenberg’s much heralded “combine-painting” which rocked the New York art scene years ago by its incorporation of a stuffed goat with a rubber tire around its middle.

Rauschenberg’s inconoclastic combine “painting” – Rocking the Easel Art Crowd

This is all pretty much old stuff by now, but owes much to the art of Tatlin’s time. In a way similar to the artistic challenge implicit in the works of the Constructivists, Futurists and Dadaists, all three of these works question the standards of what constitutes painting and sculpture. They represent a synthesis of attitudes as well as of techniques and materials. Their form constitutes a serious and apparent result of choosing this method of making a statement, and the audacity and unexpectedness of the forms is as acerb a commentary in spirit as the urinal Duchamp appropriated and signed and exhibited as an artwork. The keenness of their irony resides in the carefully considered tension between serious, biting commentary and ribald irreverence. Tinguely’s wacky, unsystematized system of utterly inefficient mechanical parts, in its pixillated pilgrimages, mocks not only society’s worship of planning and accuracy but also suggests the effervescent freedom to be discovered in random play. Tinguely’s work (his suicidal creation that destroyed itself in New York, his holocaust in the desert) turn the seriousness of the Constructivists inside out. And yet there is obvious logic in the “metamechanique’s” structure as related to its function. Like a Rube Goldberg creation, it is amazingly efficient in its inefficiency—as if Tinguely were getting away with the boast that “it doesn’t work well.”

Vinyl Sheets & Sagging Potty

Unless one is prepared to accept this kind of creative confoundedness, Oldenburg’s “soft” wares don’t allow you entry to the sanctum of their inner meaning either. Oldenburg’s whole series of softies are researches into the nature of materials and surfaces and the average human being’s sensitivity towards them. They mock modernity, comfort, habitual ways of seeing. They have a conscious environmental aspect since Oldenburg groups them together or develops them as fantasms of a familiar reality, such as giant hamburgers and french-fried potatoes of colored fabric or painted plaster.

Claes Oldenburg’s “Soft Pay Telephone” – Changing the Face of the Familiar

Like Pop painter Jim Dine’s “bathroom paintings” which combine the pictorial and the real object, Oldenburg’s works fasten on common motifs of everyday life to act as medium in structural or surface experiments—the bathroom, the bedroom, the kitchen, the automobile. Something like the perverse reversal of the man who tries to inscribe the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin, Oldenburg has constructed an entire bedroom, oversized, sharp-edged and clinically chilling, with vinyl sheets and Formica lamps, and produced his own bathroom with sagging, vinyl potty and sink and medicine chest. He has rendered “soft” automobile parts, pillowy engine blocks big as sides of beef, in kapok-filled canvas. His huge “soft” fan drooped prominently overhead in the U.S. Expo 67 pavilion. There’s, a cool snicker of Dada in his transformations of metal and vitreous china surfaces into floppy Raggedy Ann fabrications, but in the whimsical context of Pop, this is a mark of singular success.

“A Real Piece”

Rauschenberg’s “combine-paintings,” employing stuffed animals and birds, electric lights, tin cans, chains, etc., are extensions of the inclusion by Picasso, Boccioni or Duchamp of actual objects in their works—and are relatively no more audacious or original than their measured attack on the conventional picture plane. As early as 1911, Boccioni made a sculpture entitled “Fusion of a Head and a Window” that incorporated a piece of window frame. In 1920, Duchamp produced a scaled-down French window (with the panes covered in leather) called “Fresh Window.” Juan Gris, points out William Seitz in “The Art of Assemblage,” once put a fragment of a mirror in one of his pictures. When asked why he replied, “Well, surfaces can be recreated and volumes interpreted in a picture, but what is one to do about a mirror whose surface is always changing and which should reflect even the spectator? There is nothing else to do but stick on a real piece.”

The “real piece,” the thing itself, is what preoccupied Tatlin and his contemporaries. They were tired of tepid symbologies, weary of labored appearances. But other more obvious relationships show up in today’s modern art akin to the standards and transformations of Tatlin’s time. A Russian critic, Nikolai Punin, writing on Tatlin’s tower said in 1919: “There is no painting without a spatial (or more specifically plastic) comprehension of form, no sculpture without architecture or pictorial culture, no architecture without painting and space. The architect, the painter and sculptor must participate to an equal degree in evolving and executing the modern monument.” Punin, immersed in the political utilitarianism that would harden into the strictures of Socialist Realism, was describing a prophetic party line. But he might have been writing about what has come to pass in art today.

Which Space Is Real?

At no time since the ferment of European strains of Cubism, Constructivism, Futurism and Dada has such a galloping synthesis and cross-fertilization among the individual arts occurred as is occurring today. We are just witnessing now the peak of the revolution in spatial concepts visited upon mankind by the discoveries in physics in the early 1900s. Kandinsky published his theories of spatialization as early as 1912 in “Concerning the Spiritual in Art.” Moholy Nagy subsequently listed some 40 “different” kinds of space available to the artist, including cubic, metric, hyperbolic, limitless, elliptical and “n”-dimensional. Like Cezanne’s perceptual-conceptual stroke of genius, this preoccupation and prevision was already being confirmed in the work of physicists such an Thompson, Rutherford, Bohr, Heisenberg and later Dirac. The physical discoveries transformed the artist’s view of his world as significantly as Cezanne or the Constructivists, who presaged these revelations. The physicist divined the answer to a central Constructivist question, which space in the real space? The answer may be found variously in the handbooks of Physics or all across the spectrum of modern art.

Enter the Technicians

Critic Punin, an accomplished hack, wrote much better than he realized. Painters and sculptors today, in their forms and approach, are looking more and more synonymous: the shaped painting and painted sculpture share increasingly similar qualities. Both painter and sculptor tend to create on a scale that tends towards architecture, either in sheer size or environmental arrangement, to a point where the confines of traditional museums can no longer contain them. The scientific aspects of serious research, technological innovation, an emphasis on autonomous systems and comprehensive function pop up in the work of the primary structuralists, minimalists, kineticists. Electronics, computerism and cybernetic theory links now bring technicians into collaboration with artists. I remember a lovely comment from an English art review about the technicians, “Just wait until the guys at Bell Laboratories recognize that they do not need outside ‘artists’ to identify (usurp) what they have achieved and are trying to comprehend day by day.” When you think about the Constructivist’s reverence for inherent properties of materials and processes, the remark does not sound farfetched.

Big Mama’s Manifestation

The Constructivist heritage, again probably through Hulten’s affinity for their principles, was perfectly manifested in the event-structure called “She” which seemed to conform completely to the precepts of Tatlinism. “Unlike most of his contemporaries,” says Hulten of Tatlin, “he did not regard the question of determined form as essential; he was investigating artistic expression’s actual form of manifestation, its psychological existence.” Few observations better describe the aesthetic direction of the modern arts today—or the remarkable happening from which the Moderna Museet drew much of its acclaim and attention. Without the whiphand of politics over his head, Punin would probably have devoured his hat in sheer celebration of artistic synthesis. Bigger than Tatlin’s tower ever got, “She” was probably the biggest modern art mama ever to have been walked through. If not the only.

Niki’s Thing

“She” was a product of collaboration, or collusion, between Niki de St. Phalle (whose Nana dolls with ballooning bosom and backside are well known), Tinguely and Swedish artist Per-Olof Ultvedt, whose wood and iron motorized constructions are enormously witty Punch-and-Judy shows of kinetic whimsy. But from the beginning “She” seemed to be primarily Niki’s thing. Built of metal pipes and trusses, wood, chicken wire, fabric, glue, “She” was 82 feet long, 30 feet wide, six tons of proto-mythic womanhood reclining in the timeless position of birth and procreation and three stories-worth of internal visual and auditory happenings. In various parts of her brightly painted anatomy were located a cinema, a pond with mill-wheel and fish, a bar with a bottle-crushing machine, an art gallery of faked masters, a radio station and television niche. From a bugged “lovers’ corner,” whispered sweet nothings were transmitted to a speaker in the bar. A mini-planetarium lit up the dome of one breast. Even a public telephone booth (that’s “public” not “pubic”).

As a walk-through, environmental structure, “She” was the most ambitious aesthetic fun-house ever produced by artists, and the crowds proved her popularity. Lines of visitors, which passed a sign stenciled on the inside of one great thigh reading “Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense” before entering through the doorway of creation, wended their way up and down the inclined ramps and along the passages programmed for surprise and pure delight, climbing to pop their heads out at her navel to survey the entire majesty of pastel, supine bulk, while her insides throbbed with recorded organ music by Bach, mechanical squawks and rumblings and the crunch of the bottle-crusher. A perfect example of art as event and function rather than treasured product, “She” was built in a month and torn down in three days after the exhibit closed.

Constructive Dirty Work

Officially, “She” was billed as “a cathedral.” Expectedly, she generated some highfaluten free-associations. Said one Swedish artist: “She is reminiscent of both the Sophia mosque and the Willendorf [Venus], she is a dilated hatcher—who herself resembles an egg. ‘She’s’ posture is that of generation. ‘She’ is the ancient Great Mother...” But “She” was as much the mistress as the mother of us all. In her teasing form and content, she is unmistakably the shape of art today, tricked out as a sense-tickling seductress, mock-serious, mock-shy, to be explored and savored, marveled at and laughed over, a fickle temptress whose favors are lavishly squandered and whose heart is never to be quite fully trusted. But, more notably, a subtle blend of the sacred and the profane, recognizably in the vein of reverent put-on of much of today’s modern art.

Since “She” was born from the germ of an idea of Hulten’s that some sort of cooperative venture would be welcome at the Moderna Museet, the creation of the huge Nana bears a relationship to the Tatlin tower that seems not quite coincidental. The pictures of the building of “She,” published by the MM in a large newsprint catalogue narrative called “She”—A History, are strikingly similar to the pictures of the construction of Tatlin’s tower provided in the Tatlin exhibit’s catalogue (which is in itself a valuable, carefully compiled document). The same feeling infuses both sets of photographs of helpers pitching in, the pleasure of constructive dirty work, the creation taking shape and form, an aspect of art history being forged. A similar element of aesthetic theatrics animates both sets of catalogue pictorial histories. Tatlin did a good deal of theatrical set designing, employing the principles of Constructivism, and once even wrote a detailed treatise on how to produce a perceptually pleasing simulation of the moon on a theater stage. An important exhibit of the Bauhaus in Stuttgart some months ago included similar photographs of that famous movement’s theatrical productions and some of the actual costumes—and one could not help drawing parallels between their aesthetic experiments and the happening-theatrics and event-structures of today’s artists. One cogent example might be the Bauhaus costumes and those that Pop artist Jim Dine designed for a production of Shakespeare’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream,” in Toronto. But those parallels are another whole subject.

Another comparison that is more interesting between Tatlin’s tower and something like “She” involves what went on (or was have to gone on) inside both creations. The one crucial thing about Tatlin’s tower that has purposely been left out of this description was its function, its utilitarian social purpose, its (to be blunt) raîson d’être. Tatlin’s monument to revolutionary idealism and social possibility was designed to be used as a vast agitprop center, a concentration of media- and muscle-power for spreading the Soviet’s new order of society—in short, a propaganda machine. The huge internal forms of the tower—its cylinders, pyramid and hemisphere—were to be offices, broadcasting studios and garages to house the revolution’s word-smiths, slogan-builders, shock-troops.

Tool

Punin, the aforementioned critic, blithely outlined the political utility, of Tatlin’s artistic creation in 1919--at considerable length: “The monument contains also an agitation center, from which one can turn to the entire city with different types of appeals, proclamations and pamphlets. Special motorcycles and cars could constitute a highly mobile, continuously available tool of agitation for the government, and the monument therefore contains a garage…One can also attach a giant screen, on which it is possible in the evenings with the help of a film reel—visible from a great distance—to send the latest news from cultural and political life throughout the world.” Punin writes with relish.

“For reception of instant information,” he goes on, radio, telephone and telegraph facilities should be installed. He speaks of a “projector station” to beam revolutionary messages into the sky, and closes: “In principle, it must be emphasized, to begin with, that the various elements of the monument should be fitted with all modern technical aids to promote agitation and propaganda, and, secondly, that it should be the centre of a concentration of movement; there should be as little sitting and standing in it an possible, people should instead be mechanically led round, up and down: sometimes there will be glimpsed the powerful and laconic expression of an agitator, sometimes messages, decrees, regulations, the latest invention, an explosion of clear and simple thoughts, creating, only creating...” Sadly, Orwell’s “1984” personified.

Eloquent Silence

Punin’s kind of creation is one the world has come to know well enough. Could George Orwell have done better than Punin’s description? I doubt it. There is no reason to doubt as well that Tatlin, whose consuming passion was art, agreed to go along with any plan for his tower that would allow him to keep working on it. One contemporary offers a touching remark of absolution: “Tatlin himself maintained that he saw in this monument only a construction of iron and glass,” wrote Malevich, “he passed over all its utilitarian functions in silence.” It must have been an eloquent silence. His silence didn’t do Tatlin much good though; he fared badly during the icy 30s when Soviet art became utterly politicized and hardened into the sort of Socialist Realism guide lines that more than three decades later served an the symbolic instrument for the indictment of dissidents.

Creative Soaring: “Letatlin” Never Let Him Wing Away from Trouble

Tatlin fell from favor. He reverted to his former “realistic” painting style around 1935, ended up experimenting with wings of fabric and whalebone and wood to enable man to fly unaided. Leonardo-like, Tatlin gathered scientific data from aeronautic manuals to work out the delicate designs of his flying gear, which he dubbed “Letatlin,” a mixing of the Russian verb “to fly” and his own name. “What practical purpose does your apparatus have,” an interviewer asked him in the old, deserted tower in which he worked. “The same as a glider,” replied Tatlin. “Has the proletariat no use for a glider?”

Grosz’s Cameo

The proletariat, it appears, had other pursuits to think about: revolution and technology, horsemeat and cake crumbs. Tatlin was forgotten in the crosscurrent of holocaust that swallowed millions in Soviet Russia. George Grosz, the famous, vitriolic German artist who had lauded Tatlinism at its inception, provides an apt, closing for the museum’s Tatlin exhibit catalogue: “I met Tatlin, the great fool, once again,” writes Grosz of a visit to Russia. “He was living in a small, ancient and decrepit apartment. Some of the hens he kept slept on his bed. In a corner, they laid eggs. We drank tea, and Tatlin talked of Berlin ...Behind him a mattress, entirely consumed by rust, was leaning against the wall; on it sat a couple of sleeping hens, their heads in their feathers. This was the good Tatlin’s frame, and when he played his homemade balaika...he gave the impression not of an ultra-modern Constructivist, but of a piece of genuine, ancient Russia, as if from a book by Gogol; and there was suddenly a melancholy humor in the room.

“I never saw him after that,” Grosz’s cameo (with an air of fond epitaph) ends, “and I never heard anyone talk of him or of the once so busily discussed ‘Tatlinism.’ He is said to have died alone and forgotten.”

Postscript: Tenuous Parallels & Technology

Tatlinand his principles were not, of course, forgotten for long. Those contemporaries who fled West infused the arts of Europe—and later America with the regenerative “Tatlinism” one finds in modern art today. But the Moderna Museet’s monument to Tatlin resonates beyond art with some interesting historical parallels, however tenuous, in technology and politics as well as art. As in Tatlin’s epoch, art today (like society in general) is in a period of tremendous change and synthesis. As then, evolution has in fact been discarded in favor of revolution, especially among the young, with the attitude prevailing that violent upheavals must shake the body politic. As then, the young revolutionaries, and their less dewy seers and spokesmen, promise the possibility of a new, more just society, to be built on the ruins of the old, unjust one. As then, the communications media (on a scale even Punin could not have dreamt) circulate the revolutionary creed and tactic—whether by advocacy or by the mere reporting function. (One might even say that Punin’s dream for the interior of Tatlin’s monument has come true; the capitalistic media network has ironically become an agitprop center in spite of itself). As then, the artist, as a member of the “avant-garde,” is asked to commit himself to radical social change, or at least preoccupy himself with social problems—on a scale that seems even more organic and manifold than the activism of the 20s and 30s in America.

Labor-Saving Devices

As in Tatlin’s time, social transformations of a staggering scope are forecast and mankind is exhorted to hasten their arrival by cooperating with what is cast as inevitable technological development. Here lies the most fascinating, and forbidding historical parallel: as then, a relatively unproven mystique (Marxist-Leninism then; the technological necessity doctrine now) is advanced as the way to a recreated society or a pragmatically planned mode of living. One might well regard Marxist-Leninism and technological autonomy in the same metaphorical light: as comprehensive, major labor-saving devices in the history of man—labor-saving in that they incorporate, function and increase their authority by appeals to efficiency or inevitability. The idea is that they develop autonomously, regardless (relatively) of man’s intervention. Men need only read the signs, or the rules, and proceed accordingly. The process reminds me of MacLuhan’s teasingly blithe implication that the electronic media use us, and not vice versa, in their development. Historical process will be achieved despite the acts of individuals; technological necessity will be fulfilled despite the resistance of reactionary humanists. So run the familiar Q.E.D.s.

Faith & Servitude

The labor saved, I obviously feel, is the individual’s authority to order his life or have some real say in its regimentation. In Tatlin’s time, one was urged (not to mention coerced) to get in step with History, whose irrevocable current often swirled with some nasty debris. Now, we are urged (and very differently but no less effectively coerced) to get in step with technological progress. The prominent position of faith and servitude in both periods can hardly be missed. The stakes—the promised benefits if we cooperate, the avowed catastrophes if we do not—are increasingly represented as so high, so comprehensive and so interwoven, we are projected into a realm of contingencies that almost need a magician’s incantations, or a faith in magical solutions, to work out our problems. In much the same way Tatlin’s epoch was told that the infallibility of Marxist-Leninism would recreate the needed social structure, we are told that the potential of computerization and cybernetic design theory can—and must—solve the burdensome problems of modern society with an accuracy and speed that far outstrips mortal abilities.

But the technocrats are asking us to give up something quite precious—little chips of autonomy, individuality and personal privacy that add up to a vast mosaic of invested authority and power which will surely be grabbed or assumed by someone. MacLuhan quips, “the computer banks build and you dissolve.” He may be right. Like the Russian revolutionary’s Leninist apostolic creed, the technological declaration of faith, and concurrent covenant of servitude, constitute a major gamble for each individual and for the collective, or elective, voices which supposedly represent him.

Pollution Addiction

Skeptical of a technological takeover by gently deceptive degrees, some critics have remarked the rather glaring nuisances of our proliferating technology. We have created astonishing networks of labor-saving devices and informational systems; we have eagerly assimilated them into our lives and adjusted our lives accordingly; we cannot hold back progress or unlearn discovery, of course. Millions of people would not probably feel complete without a daily intake of the sensational, usually bad, news transmitted via television, radio or newsprint. The body, scientists assert, can become addicted to air pollution. In the same way Eric Hoffer points out that people in a dictatorship tend to write off governmental crackdowns as hostile acts of nature, we write off traffic jams, regional power failures and our eroded privacy to some sort of unkind destiny. We have, as Jacques Ellul precisely implies, already made our contract with the “necessity” of technological progress. If its processes and products poison our air, gobble up our landscape, constrict our cities with drone-like monotony and density…well, there must have been a hidden clause somewhere, the importance of which we failed to realize.

Tatlin’s time was marked by economic determinism and an actually mechanistic view of mankind; the problem of masses to be molded. The spiritual categories of existence were altered by fiat: “During the epoch of reconstruction technology determines everything.” No less an alteration is implicit in today’s atmosphere of “inputs,” “programs,” “systems,” “networks.” Tatlin ended by trying to discover how man might fly, alone and autonomous, tinkering there in the tower of a Moscow monastery with the will of the creator as well as the artist. One cannot help but wonder whether in the back of his mind, there was also lurking a will to discover how a man is induced to give up his freedom before he can fly away.

Picture credits: K.G.P. Hulten, Moderna Musset and tower model: SKO. Others are by courtesy of the Moderna Museet.

Received in New York September 26, 1968.