A Synaesthetic Smorgasbord: Venice & Kassel

A Synaesthetic Smorgasbord: Venice & Kassel

July 22, 1968

S. K. Oberbeck

Mr. Oberbeck is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from Newsweek, Inc. This article may be published, with credit to S. K. Oberbeck and the Alicia Patterson Fund.

Sivert Lindblom's stony silence -- Blending Man, Motion & Architecture in Venice

Amsterdam—International art festivals are like childrens’ birthday parties. They tend to over-indulge you with ice cream and cake. The recent art exhibitions at Venice and Kassel, Germany—Biennale and Documenta IV—were no exception. After both, one feels the need for some sort of synaesthetic Brioschi.

Both events have taken their rightful place in the pantheon of major art whing-dings; Venice’s Biennale as the party to be at, and Kassel’s Documenta as the party where you see the latest in artistic fashion. The Biennale, this year the 34th, displays its art from national pavilions, while Documenta exhibits more by style than by nationality. Prizes are awarded at the Biennale, which has made for some sly Venetian politiking in the past; Documenta bestows no prizes—but there is a Machiavellian contest for gallery space. Like the good dowager she is, the Biennale ends up with a respectable artistic guest-list that runs from traditional-decorative to ultra-modern. By comparison, Documenta looks like a Klopstockian congress of rampant Avangardismus.

Champagne & Beer

What ties the two exhibitions together (other than their opening within weeks of each other) is the fact that they represent, in tandem, Europe’s most impressive ovation to the modern visual arts. The Biennale promised almost 3,000 works by artists from 14 different countries—but because of student protest, some pavilions closed down in sympathy, the Russians dropped out (mainly since their works had been misconsigned to Czechoslovakia) and two highlight exhibitions surveying half a century of sweeping art evolution never materialized. Organized by professor Arnold Bode to fill the post-war modern art gap in Germany, Documenta marshaled some 1,000 works by 150 artists from 12 nations in two neoclassical buildings and a spacious park, overspending its budget of 2-million DM. The North Hesse town’s student scene was markedly different from that of Venice: when Documenta’s empty coffers ruled out a big press party, the art students, with lightening ingenuity, put together a champagne and beer blast complete with rock band and multi-screen movies that sent happy revelers home bleary-eyed.

Since many artists showed works at both events, similarities between the Biennale and Documenta were inevitable. If categories are of any use, the combined works represented a spectrum of preoccupations that ran from man, structures, environments, sensory research and development and technology to happening-like events. But the interesting aspect of the shows was how synaesthetically the artists worked, blending, juxtaposing and superimposing art categories in single creations.

Priapic Package

Just about every current phase of modern art was in evidence, pop, op, ob, funk, mini, luminal, kinetic, color-field, systematic painting, primary structures, combine, environmental—even air and package art in the form of Bulgarian-born Christo Javacheff’s “5600 Cubimeter package,” a 100-foot long polyethylene bag filled with helium that was intended to tower as a Documenta beacon. Christo has packaged everything from buildings to trees, but he seemed to have met his match in air. His gigantic white-hope, only partially filled, heaved and humped in the gusty Kassel winds like a restless larva but never got into the air for more than a few minutes. In fact, it almost floated off when its handlers lost control of its tethers (my wife and I were enlisted by shouts of “help” to grab lines with others and hang on as anchors to keep it from breaking free!). Some magazines ran photos of the gasbag’s priapic proportions, but they were doctored superimpositions. One bystander thought Christo should go back to wrapping bread.

Figurative Snorts

In Venice’s neatly manicured Giardini two Vaporetto stops from Piazza San Marco, palm-shaded, swept-gravel paths led to the Biennale pavilions. This year’s standouts were the Japanese, British, French, Brazilian and American—though the U.S. ten-artist show, emphasizing the figurative and assembled under the Smithsonian’s aegis, drew some resounding snorts of dissatisfaction.

It was packed—with too much overcrowded art as well as visitors. Norman Geske, director of the University of Nebraska art galleries, chose the show and defended as “new” the somber romantic realist and semi-abstract figure paintings by Edwin Dickinson, Richard Diebenkorn, Fairfield Porter, Byron Buford and James McGarrell.

Reuben Nakian’s craggy, elephantine abstract sculptures, pocked torsoes and thighs looming like erotic clinkers, and Frank Gallo’s creamy, vacuous-looking epoxy sexpots just inside the door provided a racy entry to the exhibition. But it dwindled into a contemplative afterglow in the presence of the comparatively serene paintings. With Leonard Baskin’s brooding work, they offered an alternative to the brash, brassy pop image America has been exporting, but in the compulsive “what’s new” atmosphere of the Biennale they tended to get passed over.

Red Grooms’ sprightly construction “The Alley” mirrors elements of “Chicago”

Our playful exception was carrot-topped Red Grooms’ sprightly amusement park for the eyes, “City of Chicago,” a room-filling, three-dimensional cartoon of painted wood and paper that commemorated the Windy City’s historical highlights in a colorful series of raffish caricatures. In pop-eyed pastels, pasteboard effies of Al Capone, Abe Lincoln, Jane Addams, “Little Egypt” and Mayor Daley populated such familiar landmarks a Louis Sullivan buildings, Marina Towers, the Art Institute lions, the El and the Loop—all towering this way and that in tipsy technicolor. Grooms’ whimsical urban microcosm—which was wired for suggestive city sounds, was a great hit, especially with Europeans. They stood around wreathed in puzzled smiles, or crouched, squinting and serious, they moved around the mini-city trying to line up good camera angles.

An environmental aesthetic was equally operative at the Japanese and British pavilions, among the most heavily attended. Jiro Takamatsu’s soaring, expansive “Dimension Perspective” was a forceful projection of Renaissance space into separate, almost clinical elements, suggesting a kind of endless, modular extrapolation. It possesses a mixture of the primary-structure, visual-research qualities, but its forceful architectonics and pastel angularity seem as well an ironic comment on the lack of humanity one finds in the urban planner’s idealized drawings—in which people often are rendered as two-legged lollipops. Takamatsu’s construction appears approachable from a number of different directions.

Eerie Modules

A clinical ambiance permeates Tomio Miki’s mirror-finish casts of the human ear, this artist’s trademark for years. As some artists concentrate on variations of the square or sphere, Miki works on ears—which would seem to lend a certain monotony to his work’s content. But it does not. The ear is fraught with associations from the MacLuhan notion that the globe is becoming again ear-oriented to the idea that the ear is a sly way of pointing out our eye deficiency. At the pavilion, two giant casts of the aural organ stood next to a series of ear-encrusted modular blocks, ranged like some forbidding public housing project and flushed with red and blue spotlights that reflected back over to the two large casts. It felt a bit like Big Brother brooding over his hosts of human integers, all cast in the same mold.

The British pavilion, spacious and bathed in a diffuse Venetian light, ranked a battalion of Phillip King’s smooth, angular menhirs and monoliths with Bridget Riley’s lush, vibrant op canvases whose sheer size quickly creates an overpowering sensory environment. Shimmering with variations in visual tempo, they also surround one with a sort of orchestrated eye-music. A different kind of kinetic suggestivity lurks in King’s precariously slanting slabs and somberly monochromed columns, whose initially stark arrangement ends by inviting exploration. People tended to wander freely around these groupings, sizing them up like benign behemoths frozen suddenly in movement.

Heat-Haze

Both Riley and King, who would appear to be working in the objective area of visual arts, bring up what strikes me as a critical question: the difference between what you see and what you think when viewing works rooted in the optical science or primary structure areas. Riley frankly admits that, rather than conceptualizing paintings along purely optical science lines, her ideas derive from personal experience—“heat-haze over a plain, or a shower of rain obliterating the geometry of a pavement or a hillside of shale spatially disintegrated by light...” King’s catalogue, on the other hand, opens with this phrase, “The sculptures of Phillip King are not symbols: their references do not extend beyond themselves as self-contained, concrete images”—the primary structure gospel in a few words. But wishful thinking, I think.

The problem, perhaps, is that the average viewer of modern art is not prepared, nor educated, to exist in a climate of emotionally inert formalism. He does not possess the background or appreciation of the perceptual researcher’s preoccupations. One tends to pass through Riley’s optical scientism and seek an analogue of what inspired the artist—the “heat-haze” or the sight of a mountainside in the light of a lowering storm. King’s sculptures, however non-symbolic, cannot help but resonate with associations in the public eye. We come to art, after all, with “literary” associations, the bane of formalists.

Kinetic Compensation

Much of kinetic sculpture, for instance, is just static form animated by a motor—but it is the description of movement that the human mind embraces, and even projects onto the static: the cartoon and the static television image depend on our ability to provide kinetic animation. Beyond this, we are still essentially a “literary” society in our approach to art; we come to the museum with story-line values that readily shepherd our reactions into fields that relate to experience: man and the human condition. Looking at some of the “minimal” artworks, I was reminded of the Miesian notion in architecture that “less is more.” The less these artists supply in their cool, clinical primary forms, the more your mind does. Unless, perhaps, you are another minimal formalist.

None of these problems presented at the French pavilion, which had closed down in sympathy with the students who had occupied the Fine Arts Academy back in town and picketed the Biennale. I had been looking forward to seeing some of Nicholas Schoffer’s new kinetic and optical sculptures, which beautifully exemplify art’s “amour débutante” with technology. No less technologically oriented are Piotr Kowalski’s neon-fused works of polyester and plastics, often animated by electronics, which sensually investigate the hidden properties of primary forms. “My work is closer to science than to art,” Kowalski told a German television team. But the Russian-born artist, who has studied at MIT and worked with architects I. M. Pei and Marcel Breuer, was one of the most vocal student sympathizers. He papered over the entry to his portion of the French pavilion with brown paper (later replaced with a spanking white-painted barrier) on which he pasted up a photograph of French security police laying into a Paris manif demonstrators and scrawled in a tri-lingual note: “Closed: Under these conditions we don’t open.” Schoffer and Dewasne followed suite. Neo-Dadaist Arman, who entombs everyday objects in blocks of lucite, did not.

Body Building

The Swedes closed down as well, draping their pavilion windows with black plastic sheeting and posting a large mobile sculpture outside with a sign that read: “Sculpture Closed.” Again, the closing was a disappointment, since the Swedes showed the best Scandinavian works: Arne Jones, who works in monumental steel and aluminum constructions, creates a deliberate flux of architecture, implied movement and the human form. And Sivert Lindblom quite literally blends man and architecture by projecting the human profile (his own) into a kind of cornice, as if one had run a template of the face across a block of damp clay. The resultant image is one of anonymity and motion, the human body oddly divested of its momentary uniqueness in a blurring streak through space.

It is always possible to find correspondences in the work of different artists; art is an international fraternity, with much visiting between houses. Lindblom’s eviscerated images fascinated me, more so when I found a Spanish artist at the Biennale working in the same image. Lindblom also renders man as a cornice-like profile or a spindle like a lathe-turned chessman, conjures up the human image out of “emptiness”—negative space, says the artist, “that the spectator can himself ‘fill in’ and therefore really experience.”

Posture Pictures

The experience is chilly and clinical, and loaded with implications of society’s glossy, machine-tooled consumer ethic. The seamless, egg-smooth human image relates to American Ernest Trova’s armless, androgynous chrome-plated torsos he calls the “falling man.” Trova’s figures, often fitted with abstract machine-parts or entombed in plastic boxes, do not stumble; they go down like a felled oak—but carelessly, dreamily, almost lifelessly. Every bit as movingly static as Lindbloom’s revolutionary torsos and negative “space” men, Trova’s tumblers also seek to denude the body of its psychological myths and historical associations—not to mention its sex. They tend to be neutral, non-literary, intriguing, unlovely. MacLeishly, they do not mean, but are. Yet so are we, and Trova’s “men” remind me most of those mythological freshman posture pictures of Smith College girls which Dartmouth men were always trying to purloin.

If Lindblom and Trova, and maybe George Segal with his plaster-cast cronies, seek to strip away centuries of emotive layers from the body, Marisol, the Venezuelan artist who works in New York, consciously constructs mythologies in her body-blocks of wood fitted with molded hands, faces, breasts and otherworldly appendages. Her chunky totems usually stand in groups, hovering between art and life like eclectic prototypes of some pop-art Frankenstein.

Brilliant Green

Before leaving Venice, I witnessed probably the best happening I ever ran across. One morning, the canals around Piazza San Marco had turned from their usual color of city-room coffee to a brilliant, emerald green, and it was the morning’s big mystery. People tooling over the myriad bridges did screeching double-takes. Even the gondoliers, who would probably simply cock a blithe eyebrow if the Loch Ness monster surfaced under the Bridge of Sighs, looked puzzled. Like, it smelled the same, but...? The answer was that an Argentine artist, Garcia Uriburu, had spent the whole night in a hired gondola sprinkling chemical in the canals to convey, he told the police with a sheepish smile, “a sign of good wishes for a finally quiet and peaceful Biennale.” Uriburu’s green was brilliant in more ways than one.

Headless Horseman

Documenta displayed such a bulk of the latest in the model arts, it seemed Venice had merely brandished the tip of the iceberg. Exhibited in two lovely, neoclassical landmarks (the Fridericianum Museum and the Galerie Schone Aussicht) and an 18th century Orangerie in the Karlsaue gardens, the works certainly did nothing to contribute to the Palladian atmosphere outside. About 57 Americans were in the show—from the jazzy pop images of Lichtenstein, Rosenquist, Wesselman and Oldenburg to the hot-and-cold-running coloration of Larry Poons, Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. Luminist Dan Flavin’s room bathed in ultra-violet fluorescent light was an impressive example of the artist resonating one major aspect of the sensory spectrum. In the weirdly shimmering u-v parlor, clothes were highlighted in psychedelic hues, while faces and hands disconcertingly disappeared in a headless-horseman effect. Kinetic luminist Gunther Uecker also provided a dark-room maze of tubular elements that winked with slits of pulsing light. And Hugo Demarco’s perpetually vibrating tiny, spheres and cones described random color blurs of movement in their surrounding u-v flush, like time-exposures of cockroaches on a hot skillet.

Squeaking Spines

While Demarco’s neurasthenic whatnots build up fascinating relationships of frantic movement, the works of Gerhard von Graevenitz and Pol Bury seek similar goals in seductively slow, minutely moving kinetics. Graevenitz’s wall constructions, circular or square, are populated with strips or cubes, each meandering in its own mysterious pattern, now fast, now (relatively) almost immobile, gently brushing, creating an almost palpable surface of interrelated movement. One begins to perceive little symphonic flourishes of kinetic program and realizes that movement, not form, is the central study of this accomplished German’s work. No less polished is Belgian-born Pol Bury, whose beautifully crafted hanging and standing constructions bristle with pegs, spines or spheres that squeak with tiny, sounds that may be inspired by the mating call of the beetle. In larger pieces, Bury has subtly colored spheres shuddering on an inclined plane, from which they refuse to fall. There is a dreamy, submarine time-scale in his tentatively questing prickles and antennae that click softly, as they brush each other, a nether-worldliness whose quiet mystery is generated partly by the fact that Bury driving mechanisms are always hidden.

Mellow Old Master

Going from the minute to the monstrous, visitors could goggle at Greek-born Chryssa’s room-shrinking neon-fused construction, scaled to Acropolitan standards and towering overhead in great snakes of red, blue and yellow. Near the Orangerie stood an oddly heavy-looking sculpture by that mellow old master of kinetics George Rickey, whose best-known works are slim metal spires and delicate vanes choreographed by the sun and wind into minutely swaying, spinning adagios of shimmering metal. But the bulk to movement ratio in Rickey’s stainless-steel “Two Planes” was a marvelous trompe l’oeil; in the wind, the two precisely balanced slabs moved in a random tandem with the ease of a child’s pinwheel. Like Calder, Rickey is a kinetic naturalist; no motors drive his pieces, only the elements. His Documenta sculpture, burnished à la David Smith, created a light-kinetic kick as it caught the sunlight and glowed with squiggles of nature’s silvery neon.

Of the primary structure people, Donald Judd’s steel-and-glass boxes (ranged near fellow PSer Robert Morris’ aluminum I-beams) seemed to epitomize the younger artist’s concern for banishing literary association—the formalism, precision and cerebral aura that permeates the works of the primary structuralists and minimalists. And yet the glassed boxes, picking up the reflections of giant color-field paintings around them, yielded a kind of liquid lyricism that softened the clinical angularities of stainless steel, bringing Judd’s lushly austere forms closer to what someone has called the “industrial impressionism” of primary structures.

Bedpan & Bra

American Robert Rauschenburg concocted an environment of sliding panels of glass covered with the images that swarm in his silk-screens—birds, buildings, industrial parts, skylines and scientific gear—that open and close when viewers trip photo-electric cells; it was a bit like walking into a mildly surreal supermarket. But the most heavily visited environment was Edward Kienholz’s morbid room called “Roxy’s”—which was the only place in the teeming Schone Aussicht one could sit down and smoke. Many did just that, though the macabre atmosphere was not especially conducive to the pleasant puff.

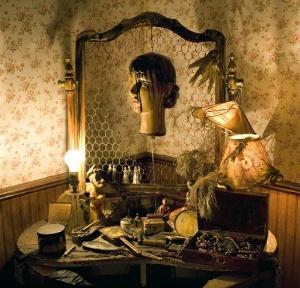

The furniture, moldy and blowsey, seemed ransomed out of a condemned brothel of the 1930s; the female “sculptures” made the mother in Hitchcock’s “Psycho” look like Brigitte Bardot. There was “Cockeyed Jenny,” a pair of artificial legs splayed over bedpan-hips, with upturned-bucket torso, black brassiere and ratty fright-wig. “The Madame,” balloon-bosomed, sported a dangling copy of “The Lord’s Prayer” and a head made from a horse’s skull. A mannequin’s blood-streaming head dangled in the mirror of a cluttered dressing table, and another piquant dummy, her throat slit and a squirrel peeking out of her breast, lay over a Singer sewing machine frame as if broken on the rack.

Edward Keinholz “Roxy” – Damage & Destruction in Dripping Detail

A master of the slimy shiver, Kienholz reminds me of the kid in the mud puddles perversely delighted by the prospect of what mama will say—or scream. His brand of visual Grand Guingol has an endearingly sick quality about it but the only positive aspect he brings to my mind is the indignant statement of a fairly morbid Southern author who said: “If I write about a rotting hill, it is because I hate rot.”

“House of the Body”

An environmental exhibit at Venice, Lygia Clark’s “House of the Body” at the Brazilian pavilion, stressed the participation of spectators and made them participants. First, an impressive array of her flexible, metal-plate geometric sculptures invited being handled and modified. Then, one browsed along tables of gloves and specially designed helmets that emphasized stimulation of particular senses. One helmet, padded, soundproofed and gagged, cut off normal sensations. Another was filled with pockets of crinkly, crackling material that stressed sound. Some were designed for hard/soft tactility; others contained mirrors, shells, sponges at the normal sensory orifices. There were sets of gloves, some thick, some thinner, with which to feel objects and even jumpsuits into which one could zip for similar sensory surprises.

An elaborate maze set various obstacles (knee-high chambers of rubber balls, profusions of entangling strings, deep-sinking foam floor, membrane-like door apertures) in the path of people who braved its ambulatory pitfalls, heightening awareness of how a body moves. A chamber in the center of the maze was laid with objects to handle like “feelies.” Some critics have marveled over Miss Clark’s sensory revelations, but it is just as revealing, and difficult, to make it to the bar of a packed London discotheque or handle a freshly landed trout.

Erector Set

Meanwhile, back at Kassel, Klaus Geldmacher and Francesco Mariotti were beating out Christo for first prize in the Documenta monumentality field with their whirring, winking kinetic construction that looked like a giant erector set. About 25 feet high, wide and handsome, the spacious flash-cube was fitted with a huge ventilating fan, presumably to cool down the jumble of electric circuitry. Perhaps the only rallying point for student protest, the untitled construction sported the red Soviet flag and a black Fascist flag as its builders, like Mohawks perched up in high steel, scampered around completing it.

There is no effective way to wrap up such a spectrum of creative impulses as was shown at Venice and Kassel. What struck me was the number of artists who, eschewing the surface image of society’s tremors, amalgamated various aesthetic currents in their works. The sense of the synaesthetic was strong. A year or so ago, sculptor David Hare remarked that the artist “just runs like hell to keep ahead of his public, who are also running like hell to keep ahead of the artist.” If you listened hard in Venice and Kassel, you could hear the sound of heavy breathing. But the multiplicity of aesthetic interests, impulses and appeals in the Biennale and Documenta works made me feel as if the artists, tired of the public’s breath on the back of their necks, had broken the field, left the track and wandered off in the woods to explore their artistic capacities in peace.

My most deeply treasured memory of Documenta (analogue to the green canals) is of a photograph I missed—of a uniformed guard in the Schone Aussicht. He was bending down in a room full of weird sculptures and wall-hung works, peering intently at the label of a big, red fire-extinguisher on the wall. Which, incidentally, didn’t look bad…

Postscript: Student Protest

There were almost as many students as reporters to cover them, and they had already occupied the Accademia di Belle Arti and mounted red flags and protest posters by the time the press men passed that way along the Grand Canal. As the vaporetti yawed into the Accademia stop, people gawked and strained to make out the “big character” posters the students had put up. “Occupazione totale” read the sign over the Academy entrance, guarded by student sentries. There were meetings of the dissidents, to which sympathetic artists such as Kowalski came. Red Grooms and his aides (who helped him install “Chicago”) attended one meeting, but told me that when they saw some volatile Frenchmen had taken over, they got bored by the argumentative bureaucracy and started to leave. The door was barred, said Grooms, as was their path—by a “revolutionary” who informed them they could not leave until the session was ended.

Tomio Miki “Ear” – Was the public listening to the Student Protest?

The day before the events in Piazza San Marco, some students paraded through the scolding pigeons with red-painted picket signs, raising an eyebrow or two among the Venetians and tourists seated at outdoor cafes on both sides of the Piazza. The signs protested the presence of police (visible only at the Giardini site in any number) and bourgeois, capitalistic society in general. It was curious that the students protested the police presence they so carefully attracted. “Look here,” fumed one irate visitor, “they come in shouting they are going to tear up the Biennale as they did in Milano and then start marching around like saints when the cops come out with their down-with-Fascism signs. It’s absurd.”

Protest Process?

Given the unconscionable fact that Venice is basically a bourgeois tourist town full of fabulous art treasures, it was no surprise that city fathers would ask police protection to stem what seemed inevitable provocation. But this seems to be the growing process of the protestors: challenge order when you are assured of resistance; provoke resistance to do its worst; then denounce the brutality that was the objective in the first place. It is a symbolic process—or expedient—that bears little relationship to legitimate student demands. It is breeding an atmosphere of violence without guilt (or punishment) that historically has never boded well for us.

The morning of June 17th, the first day the press were officially allowed into the Biennale exhibition grounds, I took a vaporetto out to the Giardini in a sparkling sunshine and found cordons of police and soldiers (side-armed and with batons) standing in abeyance but well out-numbering a knot of milling protestors with grim faces. One carried a bull-horn which I never heard him use. Enough polyglot photographers stood around to make any shred of “brutality” instantly international. The police that morning appeared on orders to keep down any incidents, but piano, piano. They were watching themselves as closely as the students.

Security was strict. I showed my Biennale “laissez-passer” three separate times (and they inspected it) before finally gaining entry to the exhibition proper. The men at the checkpoints, uniformed at the first (though with white gloves and gold braid) but either Biennale hosts or very artsy plainclothesmen at the remaining two, were firm, but not unsympathetic. Numbers of visitors attempted to get in secretaries, researchers, girlfriends, etc., on their passes, in most cases succeeding. But not without difficulty. “This is camera equipment, that’s all,” protested a girl with one photographer who carried his gear. “Si, si…Si, si,” said the smiling official, waving her off into a limbo of standees draped over the fence.

“Crack?”

That day went well enough. The next, not so well. I got back to P.S.M. around 6:l5 to find a semicircle of police (surrounded by a circle of onlookers) who circled in sweep formation. By the clock tower, in the little square next to St. Mark’s cathedral, the students had been demonstrating—with the announced purpose of occupying the basilica. Occupying St. Mark’s, a holy landmark (despite its droves of tourists) in a Catholic city, may slip off the fingers of the newspaper reporter like any other fact. As a stated goal, it had for Venetians connotations that reverberated beyond fact. With flags (red) and posters (militant), the students milled in the square as the caribinieri stood and awaited orders. They were described as “crack troops” in one paper, which (no disrespect intended) was a hilarious moniker for the stand-easy string of young men who chatted, joked, smoked and conspicuously eyed some tourist minis in the back of the sweep-circle.

When the crunch finally came, it was like the flurries of street violence I had seen before. The camera always transfixes this sort of impersonal anger raw, but one could see that some fairly fancy cropping of photographs had been used in the sensational news shots that were published abroad. Batons were laid on—of that there is no question. But wasn’t that the point of the protest? Or are the student affirmations of a Fascist society falsely broadcast?

Who’s Running The Meeting?

The cry the events of June 18th raised, in big, black headlines, was somehow wolfish. What does one do given a position of power (unforgiveable to the students—unless you are running the meeting), if a vocal group of dissidents who has occupied the Fine Arts Academy tell you they intend to occupy your city’s most sacred landmark and then appear next to it with red flags and angry signs? With memories of Milan and Paris, do you solemnly admit to the deplorable situation of students world-wide and throw open the cathedral doors? Do you take this opportunity to frankly acknowledge that you are a miserable bourgeois who is guilty of exploiting struggling students? No revolutionary “student” expected that.

But an even more critical question: can a student with a viable gripe expect powers almost a generation away to accept the supposed, new parameters of human existence by flouting laws and traditions on the grounds that they are unjust and obsolete? I think, sad to say, the answer is: Yes, in thunder. At least so it emerges from the most vocal militants--for whom anything short of total victory is crushing defeat. For all their sagacity, the student leaders should know that peddling a radically new order for society takes some delicate public relations. But, despite its historical mutation into a managerial problem, the revolutionary ideal seems to hold the ultimate magic for them.

Hook-And-Ladder

There was an interesting exchange at the French pavilion, where Piotr Kowalski was being interviewed by a German T.V. team. They asked him to explain his protest closing. He replied that the presence of the police was insupportable—which seemed a bit like saying that the presence of hook-and-ladder trucks at the firebugs’ picnic was unconscionable. Then a man on the sidelines—a Fairchild Publications correspondent who had been at Milan—piped up to remark that “the students haven’t come here to see the art, they’ve come to shut this place down, just like they did Milan.”

Did our Teutonic televisors ever perk up! Flash, and the camera had transfixed this blessed interloper. Kowalski rose to the challenge: “How do you know?” he rasped, visibly (and media wise) angry. “Because I was there,” riposted the Fairchild fellow, now hooked into playing antagonist. Cameras swiveled.

“How do you know what they want?” Kowalski repeated. “Let me talk to them. Let them come in here. Let’s not have these police…I want to hear it from them, not from you.” (I remembered the meeting he had attended, but the camera didn’t know that). I may be blowing a chance for a long interview with Kowalski, but be was obviously blowing through his halo.

Finally, he sneered at the correspondent that the reason he was against the students was that they had prevented him from getting his story at the Biennale. Helas, not so, Fairchild’s man answered. In fact, he got a better story because of the student storm. But that, he protested, was “not the point.”

The New Form

Yet perhaps it was. Leaving Venice a few days later, I was on a vaporetto that fetched up to the Accademia stop. And there it was: the new form of the arts, the shape of today. In the square stood the easels of the occupiers. On them, pasted proudly, were the press clippings of the Biennale brouhaha, the coverage rimmed in red-painted borders: the new Internationale, in pulp-paper collage.

Received In New York July 24, 1968.