(NEW YORK CITY) - Booker has been a barber for nearly 40 years. Although he is officially retired now, he still drops into the small barbershop off Northern Boulevard in Queens, where he last worked. If one of the three regular barbers is absent he even puts in a day's work to help out. But he returns because of the fraternity he finds here, the chance to sit and talk and swap stories with a few of his old customers. In his late 60's, his speech is hesitant now, and he sometimes struggles to find the right words. When he gets into the telling of a yarn, however, a glint, almost youthful, seems to brighten his face. It's not difficult to imagine that, as his friends point out, 20 or even 10 years ago he was the best storyteller or "biggest liar" in the area.

"It was something back then, son. You youngsters don't know we didn't hardly see no parts a no white folks back then, less they come to collect some money. Missed'um 'bout as much as fireflies miss light bulbs. I was working in Harlem, a little shop right off 125th Street. Big time Negroes used to come in there-musicians and like that, actors from the Lafeyette and Cotton Club. Tipped like money was water; only thing is most of 'um musta grew up in the desert, someplace where it was right dry Still, we had a ball back then. Wasn't all this complainin' and carryin' on. Negroes used to work, when they could find it, and then forget about the white man and go out and raise some hell. Now yall so worried 'bout integratin' you cain't enjoy yourselves. Hell, we had a few folks like Joe Louis, Amos 'n Andy and such out there struttin', but we had all the entertainment we needed right here in Harlem. Now Negroes is all over TV, everywhere. Trouble is you can't tell'um from nobody else; don't even talk like they suppose to. Saw one Negro on TV the other day sittin' up talkin' to some white folks- he was as pumped up as they was. Couldn't tell'um apart less you look real close. Boy better watch it, 'for he know it them suckers have his tail back in the cotton fields Seem to me you youngsters got everything you needs now, just need somebody to show you what to do with it."

Black humor, primarily in the form of jokes in which blacks are the butt of the jest, has been an important part of American humor since before the Revolutionary War, but little has been done to understand or appreciate the authentic nature of that humor or to explore the societal attitudes that it may reflect. Not that the subject has been ignored; the commercial media have traditionally focused almost exclusively on humorous depictions of black life. But the authenticity of these depictions is, at best, suspect, since few radio and television shows or motion pictures are controlled at the conceptual or creative levels by blacks: witness the scarcity of black writers working on prime-time television shows or major motion pictures, and the near absence of prominent black directors and producers. In the print medium, some academic studies of black language and life style have been published which, in passing, consider the subject of black humor. Several collections of black folklore and humor are also available. But few of these books seriously consider the relationship between black humor and the tacit societal attitudes of its creators.*

Both Warren and Lester work in advertising. They are graduates of black colleges in the South, and were among the first wave of blacks who broke into previously all-white professional jobs in New York City in the early 1960's. They have known each other for more than a decade and, over the years; it has become their custom to stop for drinks at one of the West Side bars such as The Cellar, Rust Brown's or Mikell's a few times a week. These meetings, in their own words, "are necessary It's where we shuck all that downtown-Madison Avenue bullshit." Observing them entering the bar in suits, white shirts and ties, carrying similarly expensive briefcases, then drop their rigid postures and slip into a kind of handclapping camaraderie, you can literally watch the tension drain from their faces. The humor, in their usually lively banter, inevitably focuses on sex and the hazards of working in the white world.

Warren: "Those suckers are insane, man. They get uptight if they even see two brothers talking to each other. "

Lester: "And don't laugh, man, ever -unless they know they're in on the joke. If you're with another brother and they're not close by they immediately think you're laughing at them. Damn, I used to think we were paranoid "

Warren: "And for good reason!"

Lester: "But they be some neurotic dudes. "

Warren: "Now what do you suppose they think two black, virtually powerless, underpaid account executives could do to them?"

Lester: "You don't suppose it has anything to do with any of those foxy little caucasian secretaries, do you?"

Warren: "Of course not man. Why would any of those ladies be interested in some niggers when they got the pick of all them powerful masculine execs; shit, man, they can go out anytime and rap about each other's hang-ups. The dudes may not be able to turn them on personally, but they can certainly turn them on to a good shrink."

They slap hands, smooth their suits, and, for a moment, assume the stiff poses they had when they entered the bar; seconds later they collapse into each other's arms with laughter. The banter resumes and, later, I ask them about the image of blacks in advertising and on television shows. Warren answers:

"Hey, man. Is there anything real in the media? Particularly anything about niggers? It's all stereotypes-and safe ones at that. In the ads blacks are always laughing, harmless, friendly folks or else they're copies of some simple white housewife exclaiming the benefits of the new this or that. The shows are all comedies filled with blacks acting like fools-even their anger over their condition is turned into a joke Now, I suppose, George on "The Jeffersons" comes close to a certain kind of real black man. But that's a special case. If you can believe he moved out of the ghetto on the basis of a hustle in the laundry business, you can go for him acting like an idiot. On the other hand, I guess we ought to be right happy that they got so many niggers on TV at all. I remember when there was none. If nothing else, it helps some of us get over."

Paul is in his late 30's. He has moved from a strict, middle-class Southern upbringing, through active participation in the civil rights movement and advanced degrees from an elite northeastern university, to a successful career as a writer and teacher. Like Warren and Lester, he frequently jokes about the liabilities of being a black professional: "They just won't let a nigger make no money out here What we goin' do?" But his observations of the shifting thrust of black humor perhaps reveals more than his personal attitude.

"Being a student in a Catholic school in the South set me apart from most blacks. We joked primarily about religion and politics, while the kids in public schools had a different kind of humor. The jokes I told never washed with the public school blacks. They thought my jokes were lame, because their humor was more typical of the 'vulgar' type humor we associate with black comics like Redd Foxx-you know, humor basically focused on sex and profanity. But even the public school blacks never joked about whites; the bitterness was repressed. Niggers told jokes about niggers. I never even knew any jokes about whites until after I left the South. I mean, we sometimes joked about some particular ethnic group, like Italians or Jews, along with the whites or Wasps-but never about whites in general. As far as I know, even the baddest niggers didn't get into that: that was like playing with death. We were taught that those people were walking Christs Even when I moved to the North, in the 1950's, blacks basically told jokes about blacks; and the humor almost always had blacks as the butt of the joke. You know, jokes about physical features, like where was niggers when God handed out good hair or you look like your nose been run over by a Mack truck. We were laughing at Amos 'n Andy just like the whites. At that time I viewed myself as an American first, despite what was going on. I never even thought about the implications of that show until college and the movement. Then it occurred to me that laughing at Kingfish and Sapphire was like rooting for the cowboys in Western movies, I was essentially laughing at whites kicking my ass. And most black Americans that I've met were doing the same thing It was the times, I didn't understand the subtle manipulations. Now I understand it; but, shit, we're still powerless to control it. What is it they say about ignorance being bliss. Like I said, man, what we goin' do?"

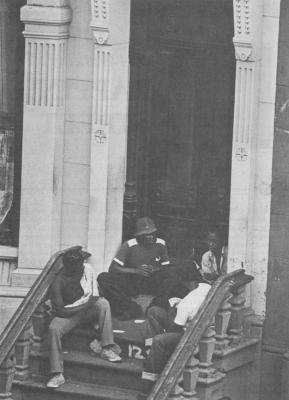

Roscoe is a slightly built youth, lean but wiry. At about five feet, two inches tall, he is the smallest of the group of teenagers lounging about the wooden benches outside this Harlem Park. But his size is no indicator of his prestige among his friends and, as usual, on this cloudy, exceptionally hot June day he is the center of attention. As he talks, his body moves continually: each phrase is punctuated by a shrug of the shoulders, a dip of the knees, a quick jerk of the head, or a dramatic hand gesture. Already, at age 15, he has acquired the rudimentary mannerisms of a stage performer. He is the clown prince of this Harlem corner.

"Yeah, can you dig it?" he says, in a singsong high-pitched voice that betrays the youth he attempts to conceal with his cool posture and raffishly doffed cap. "Some dudes be laughin' and reelin'; meantime Roscoe is on the case movin' and dealin'. I'm young and, ah, so fine-whoo, take you higher than the man's best wine. Bring you up, take you 'round-don't matter 'bout the chatter, just be cool and dig the patter -bad Roscoe is gettin' down."

The monologue is familiar, a variation of a spiel often used by New York City disc jockey Frankie Crocker and similar to the rhyme-poems popularized by Muhammad Ali. The source of the form can be traced far back into the history of black American folkways, however; the tradition has not waned.

As Roscoe continues, performing partly for the recorder and partly for his local audience, his buddies crack up, guffawing and slapping hands.

"What it is, baby! What it is," one shouts.

"Preach, little stuff. Go 'head, run it to the man," another chimes in.

After Roscoe has finished his rap and his friends start to drift away to join the basketball game inside the park, we talk. He lives in Brooklyn, he says, but spends most of his time hanging around the streets. Even on school days, as this was, he comes into Manhattan to "dig the action. " The poverty and overcrowded apartments of the ghetto, according to him, are easy to explain: "Shit, man, ain't no secret, everybody knows what's happening. The man is doin' it to us, coppin' all the meat, leavin' us the rind. [The] Dude can not be trusted, and if we turn our backs we goin' get busted." He laughs. "The motherfucker so slick he cain't even trust himself no more-can you dig gasoline costin' more than blow?"

On black characters appearing on television:

"Some of it funny, you know; but it ain't real. They got some bullshit niggers on TV. Them dudes on what they call it-"What's Happening?" they ain't nothing but punks. Wouldn't last a minute on the street before they got wasted. I rather watch the Hulk. Now that's a bad dude. That's the kind a niggers we need."

These four brief interviews provide a wide sampling of the form and varying style of humor seen in the black community. For instance, Booker is typical of the black philosopher- storyteller and is representative of a tradition that goes back as far as African griots. There is practically no black community where his type cannot be found in a pool hall, bar, barbershop, or at the center of a crowd on someone's porch. Whereas, Lester and Warren reflect the hip put-on, a more sophisticated and ironic variety of humor which is common among urban blacks who, because of their professions, divide their lives between black and white worlds. And, Paul, an intellectual, reflects the more objective, witty and analytical approach to humor that is shared by many of his colleagues- black and white. Finally, Roscoe typifies the style of black humor that is probably most familiar to non-blacks: the street hustler who incorporates signifying, rhyming, the dozens, exaggeration and broad farce into a highly stylized presentation.

Obviously, the prominent link between all the subjects is the theme of race consciousness in their humor and in their attitudes about society. Despite polls which indicate that white Americans find the problems of blacks relatively unimportant,** my interviewees were obsessed with discrimination. In fact, race and discrimination, either obliquely as with Booker or directly as with the three other respondents, remains the central theme of most inner-community black humor-television sitcoms and their bland presentations notwithstanding.

Commenting on the role of black humor in their controversial book Black Rage, published in 1968, psychiatrists William H. Grier and Price M. Cobbs wrote: "All suffering people turn in their sorrow to laugh at themselves; they laugh to keep from crying." Two years later, in The Jesus Bag, writing about the "dozens" and the apparently hostile attitudes demonstrated by participants in the game, they observed that "the dozens would seem to prepare a man to be a vicious warrior without conscience.

Not [among blacks], however, since the system makes the warrior posture suicidal."

Back in 1968, these comments were probably apt. The majority of the subjects I interviewed who were over 25 years old did in some sense reflect both the societal impotency and/or fear of white reprisal for aggressive acts to which Messrs. Grier and Cobbs refer. This attitude -of reverential submission to the white world and barely veiled fear of any contact with it-is obvious in Booker's remarks, for instance. And, although Warren and Lester, in the privacy of a nearly all-black bar, occasionally ridicule the behavior of their white fellow employees, they unhesitatingly admit that on the job they "play the game." Even Paul, however realistic his assessment of racial obstacles to advancement at higher professional levels, falls back on joking about being financially "stalled." In varying degrees, each of these subjects have capitulated to the power and supremacy of the white world. They are typical of most blacks interviewed who were more than 25 years old.

Younger blacks interviewed, however, were assertive and militant. A representative comment was: "Whitey ain't giving up nothin' but bullshit and shovels and I ain't goin' for either one-I'll get mine, my way." Although somewhat extreme, Roscoe's iconoclastic humor and irreverent assertiveness was typical of the attitudes expressed by nearly half of the younger blacks interviewed.

Of course, as one 38-year-old subject suggested, it could be that the more resigned attitude of older blacks is the consequence of prolonged encounter with discrimination, and that the Roscoes of the ghetto are merely reflecting a soon-to-be discarded, youthful rebelliousness.

But in a recent conversation, Claude Brown (author of Manchild in the Promised Land and Children of Ham) insisted: "They're for real now, man," he said. "We use to talk loud and play the dozens, signify and whatnot, but basically we were just wolfing. We might have hollered around the corner at a cop or something, then split. Now teenagers talk about killing people, parting someone's head with a meat cleaver. They joke about it, but they mean it. They'll take you out. Then it was all talk, now these cats are serious and cold. They mean it, and they don't care what happens."

* Geneva Smitherman's Talkin and Testifyin is an exception in that it both analyzes black language from an objective perspective and attempts to interpret that language (particularly its use in humor) in terms of the social dynamics of the black community.

** A 1978 Gallup poll found that whites considered "the problems of black Americans" of least importance among 31 issues offered for their estimate, and a 1977 Harris poll found that only one in three whites thought that race discrimination was an obstacle to equality.