Massage Parlors for Jaded Senses

Massage Parlors for Jaded Senses

July 15, 1968

S. K. Oberbeck

Mr. Oberbeck is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from Newsweek, Inc. This article may be published, with credit to S. K. Oberbeck and the Alicia Patterson Fund.

Jean Ipoustéguy's "Homme Poussant une Porte"-- Doorways of Perception

London—In the synergintic, all-at-once world posited by environmentalists such as Lewis Mumford, Marshall MacLuhan or Gyorgy Kepes, the glittering, twittering walk-in work of art—that proliferating sensorial massage parlor—is an example of the modern artist’s preoccupation with a new scale, form and space. In museums, galleries and arts festivals on both sides of the Atlantic, the most modern artists, with something of the cool come-hither of a psychedelics salesman, are constructing wrap-around experiences and spaces that are strikingly different from our normal environment.

Painting and sculpture, in the hands of these environmental artists, seem to be synthesizing each other: both become more and more like sumptuously colored and highly modeled architecture through which spectators can stroll, sometimes dwarfed by the creation they explore. Painting has not come down off the wall so much as it has become the wall, often one that curves or twists. Whole rooms full of found or created objects are now “assembled” to produce an enveloping esthetic experience by combine-artists like Claes Oldenburg, Edward Kienholz, Marisol and George Segal. Today’s artist, flush with the benefits of a more affluent, better educated public, is now as interested in a captive audience as in a captivated audience. He is no longer inviting you to peek into his world through a picture window on a museum wall; he is building and beckoning you to come right into the house itself—which is usually designed to catch you with your ideas down and coax your jaded senses into unfamiliar territory.

“Baby, Let Your Mind Roll On…”

A bit like the pop-folk song advises, the environmental, combine artist is inviting you to “Walk right in/ Sit right on down/Baby, let your mind roll on ...” In America, examples of both cool and kinetic environmental art such as this Spring’s “Second Festival of the Arts Today” in Buffalo, New York or the more recent “Magic Theater” exhibit at Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Gallery reveal trends of the wrap-around art school which has been developing apace in Europe.

In London, the environmental approach is particularly apparent in Keith Albarn’s work and preoccupations. A 29-year-old designer who studied architecture at Nottingham University and sculpture at London’s Hammersmith School of Art, Albarn started a company two years ago (Keith Albarn & Partners, Ltd.) which designs and produces modular structures and multi-media environments for festivals, exhibitions or private clients who want anything from weather-proof golf course shelters to a children’s playhouse. His company has produced structures for festivals in London, Brighton and Windsor, a discotheque on the Cote d’Azur and a multi-media, electronic funhouse called “Spectrum” for a 200-acre amusement park and tourist facility at the coastal resort of Margate, about two hours by train from London.

Currently completed, but still subject to vetting by an official committee, is Albarn’s therapy-oriented “autistic unit” for acutely withdrawn children, commissioned by High Wick Hospital at St. Albans, a small, intensive-care facility which ministers to patients from three to 12 years old.

Albarn’s company also designs educational aids and toys for children under the trade-name of “Playlearn, Ltd.,” something on the order of Creative Playthings, Inc., in the States. It also markets highly imaginative, all-purpose fiberglass furniture and play-structures fancifully called “The Kissmequiosk,” “The Apollo Cumfycraft” and “The Tailendcharlie.” Albarn’s partner companies produce the sense-joggling electronic equipment used in his kaleidoscopic, psychedelically tinged interiors—light and sound synthesizers called Harlequin, Tranquilite, Colourgram, Lumitone and Phonolite.

Generally referred to by its North London, former-warehouse address, Albarn’s “30 Warner Street” group consists of designers and artists, filmmakers and photographers, kinetic and luminal constructionists—even actors and musicians. It has design and construction “units” and light, sound and kinetics “departments,” which is a letterhead, PR way of saying that there are some multi-skilled individuals in the young company to which various bucks can be passed and expected to stop.

Puzzles and Pushbuttons: Getting in Touch

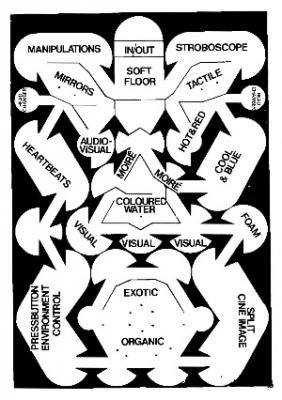

Spectrum at Dreamland Amusement Park, which cost about 10,000 pounds to complete and the autistic unit for High Wick (expected to cost about 7,000 pounds) are two fascinating examples of how Albarn applies the same materials and effects to satisfy two seemingly different sets of requirements. Spectrum is in the same vein as the multi-media environments and light works produced by the American USCO group, or the environmental exhibitions that periodically appear at the Architectural League of New York. Albarn’s “funhouse” is a series of walk-through labyrinths made of fiberglass spheres and tubes in which areas are visually, aurally or tactically designed to generate various sensory effects. There are hot/red, blue/cool areas, pushbutton-control and manipulative-puzzle sections, mirror, moire and stroboscopic passages, olfactory and tactile chambers. In short, Spectrum seeks to spice the sensory experience for fun and profit—and hopefully the titillating trip will in some way be an education in perception and enjoyment.

The autistic unit, scheduled to go into operation this Autumn, was designed for a decidedly more intensive purpose. Albarn hopes it “will function as a mini-hospital.” Like Spectrum, the AU consists of interlocking, brightly colored fiberglass modules, each about eight feet square, that can be easily rearranged to create variable shapes and color conditions for disturbed children. The interior chambers are similarly variable in terms of light, sound, color and texture—with an emphasis on manipulative devices by which a child can change or regulate his surroundings, getting in touch with his surroundings.

Aggression Areas

Explains Albarn: “An autistic child can’t communicate with his fellow humans at all, he’s almost totally isolated, and his only contact is very refined—all his normal senses may be channeled into one. Touch, for instance.” The AU is designed to exploit this “handicap”—knobs, buttons and levers change the light and color inside an AU chamber so that “when a child coordinates hand and eye, there is a simple reward result.” Similarly, in an “aggression area,” a child’s destructive symptoms will be indulged as his only form of communication with the outside world: there are regimented stacks and piles of objects that can be sent tumbling with a satisfying clatter, but can also be immediately restacked (by means of internal wiring) simply by pulling a lever. There are motor areas (“a glorified gymnasium, really,” says Albarn) and retreat areas which Albarn describes as “kind of warm, silent, upholstered wombs” which can be neutrally colored and made acoustically inert. There is also to be a section in which the child can hear amplified his own breathing as well as his speech.

Albarn's "Spectrum" Park Plan: Dodgems & Whirl-A-Boats

The AU’s imaginative therapeutic blend of the methods of Maria Montessori and B. F. Skinner evolved partly from some experiments Albarn and some friends conducted four years ago, when they set up a prototype multi-media environment in the rooms of a London gallery, then known as “The Artists’ Own,” in Soho. “We disguised the building-front so one couldn’t really tell what was going on inside and just opened the door and sat back and waited,” recalls Albarn. “The general public came in droves and took it all in. Some artists got terribly solemn or upset about it and psychologists used to come around, very interested. Just by word of mouth alone, we got perhaps 5,000 people in…I mean, all kinds: it was fun for mum and dad. A lot of people came in during the lunch hour and sat eating peacefully with all the light works going.”

Once Upon A Trip: Underground Rising

That was before the strobe-frozen, peacock-colored drug and psychedelic craze hit swinging London, which was just rocking gently then. But the joint-rolling, sugar-cube tripsters soon began to flourish, says Albarn, and “people saw in us the only material manifestation of the LSD angle. We suddenly became part of the Underground, which was rather counter to what we were trying to do. I’m all for getting the underground overground. For our sort of activity to have any effect, it must be to some extent integrated into existing society.” And integrated it is, in the case of Spectrum and the AU, which may even end up in some form in America: Albarn says he is in contact with Nancy Rambush, probably America’s leading Montessori advisor and tub-thumpper.

Besides the interesting diversity of its creations, Albarn’s commercial coterie of designers, artists, technicians and promoters seems representative of much of London’s youthful, ever-hustling network of artistically schooled and oriented hopefuls who are trying to turn a quid. In a bewildering cross-riff of skills and alliances, their group names and addresses change frequently, the makeup of “companies” goes through what seems like monthly metamorphoses. Among themselves, they contract and subcontract and sub-subcontract, drifting together on this project, breaking away on that, shifting and regrouping in offices, pubs and dance halls like cultural mercenaries. They figure percentage, and fractional fees, cajole industry for backing or materials, pitch arts councils or committees for support, and mix the elocution of staid managing directors with brassy, inside pop jargon and Carnaby Street duds.

Six Months on the “Research Team”

Casually resplendent in a green corduroy jumpsuit and green corduroy shoes, dark hair trickling over his ears and calesthenic eyebrows jumping, Albarn speaks of his associates as an esthetic family: “All our activities are directed towards a more fluid relationship between man and environment, creating an environment more responsive to man’s actions—machines, and so on. The other side to this is play; play as a social activity has ritual and pattern, and also the possibility of an open-ended situation, a degree of exploration. Our fun palace at Margate is obviously play-oriented. It’s at a fairground, after all.” Though his hip-tech conversation is redolent with rumors of game theory and “Homo Ludens,” Albarn does have first-hand knowledge of the play-ritual and its awesome implications: the youngest member of his “research team” is a six-month old baby named Damon Albarn, one of the company’s testing “experts.”

The rhetoric gets only slightly stiffer (but the message is much the same) in Albarn’s 30 Warner Street “manifesto” statement of what he and his colleagues are trying to do: “We see ourselves, through our environment, as products of the past. We must now come to terms with the present and align ourselves with the concept of change—becoming part of it. To make progress this way we must understand our environment through a full exploration of it and by creating environments which will extend our capacities for understanding.”

Today’s Medieval Minstrels

These brave and idealistic utterances, which would probably earn an indulgent nod from the likes of Buckminster Fuller or Eric Hoffer, are slowly coming into fruition in London’s cross-hatch of artistic endeavor. Albarn, for example, in taking a major part in a London festival (variously called “Summer Fair” and “Fun Fair”) taking place this month at Tower Place, in the plaza of a large office and shop building in the heart of the city. The plan is a pilot project for developing a series of mobile fairs which would visit various large cities in England, like a modern counterpart to the wandering medieval minstrels and wagon-shows that traveled the country centuries ago.

A number of artist-designer groups are involved, including Sean Murphy, who designed the audiovisual (movies and stills projected on “stones”) English “history” presentation at Britain’s Expo 67 pavilion, and electronic sculptor Bruce Lacey, who with two associates is contributing a walk-through labyrinth called “Humanoid.” It employs light, sound and textural techniques somewhat akin to those used in Spectrum, but is modeled after the human organism’s interior system—a trip that might remind some venturers of Nathanael West’s “The Dreamlife of Balso Snell,” which records a surreal, gastrointestinal pilgrimage. Lacey’s grandiose plan includes the simulation, or symbolizing, of real life’s internal processes, which involves a tremendous amount of specially designed machinery and light and sound effects.

Treading A Spongy Tongue

One will enter through a yawning pair of red, parted lips, pass beneath a row of gleaming white teeth, and treading on a spongy tongue, go down the drafty (breathing in, breathing out) throat and into the stomach—by which time one might be worrying about negotiating a steak dinner six-foot high. The lung and heart in Lacey’s labyrinth are to have expandable walls; the lung will heave with great draughts of air while rubberized “ventricles” connected to a rocker-arm will thump audibly with the beat of life writ large. A big, fancy brain unit was planned, but just how extensive this journey into the interior will be still depended on last-minute finances several weeks ago. The exit problem, however, should prove no embarrassment for even the staunchest blue-stockings: costs have kept Lacey from reproducing the entire human system, his original plan.

François Baschet's "Cristal" -- Otherworldly Music of Spheres

Costs usually seem to square off the artist-designer’s multi-faceted dream. Mike Leonard, whose kinetic son et lumiere totem-pole will be a “Fair” focal point, initially recruited French sculptor Francois Baschet to create some of his “sculptures sonores” (which are created as musical instruments by the Baschet brothers in the Baschet-Jacques Lasry synthetic music combine and have been internationally-exhibited for the audio-visual tower. But lack of funds sandbagged that part of the project.

Stone-Rolling Sisyphus

“Fair” administrator Robert Atkins, 28, admits, without a trace of rancor, that getting British business to contribute to projects such as the “Fair” is an endeavor to rival the stone-rolling of Sisyphus. While industry is sympathetic (Atkins thought Schweppes might contribute something), the Wilson government’s Mark II budget leaves little room on the balance sheet for such visionary social philanthropy. Atkins estimated that about 14,000 pounds would have been required to complete the entire spectrum of designer-artist proposals. But in the beginning, the only secure allocation was 1,250 pounds from the Arts Council. Inevitably, says Atkins, “we will end up doing the very thing we want to avoid doing—exploiting the good will and enthusiasm of the designers.”

The exploitation is for a visibly good purpose, however. “Fair” evolved from an earlier, more sweeping proposal by London drama luminary Joan Littlewood’s “Community Services” organization, which operates out of “Stratford East,” the Theatre Royal Annex, on Angel Lane, right in the middle of a shabby, hard-rock working-man’s neighborhood. Miss Littlewood, explains Atkins, has long attempted to invest art projects with social orientation and to put esthetic entertainment into the street among the people.

Her organization, news of which surfaces and fades like sightings of the Loch Ness Monster, boasts as trustees Buckminster Fuller, Yehudi Menuhin, Sir Ritchie Calder and a cousin of Her Majesty’s, the Earl of Harewood. It represents another instance of art, as spectacle and performance, moving openly into the multitudes and away from minority audiences and consumers. Of the “Fair,” Atkins remarks, “This is not even specifically art but an entertainment structure which is a branch of the theatre. Nor is it a set brief to explore new demensions. It’s really just a natural function of the designer’s training—an example of experimenting with art as education in the street.”

More Calliope than Collage

The environmental aspect of “Summer Fair” is basic and apparent: in much the same manner as recent, sizeable outdoor sculpture exhibitions in Bristol and Brighton gladdened the normal cityscape, or--as Albarn’s first kinetic lightworks were “fun for mum and dad”--the “Fair” is an attempt to modify, for the moment, the humdrum familiarity of a London neighborhood. Populating Tower Place with imaginative play-structures and colorful audio-visual creations programmed for surprises and enjoyment is as elemental an impulse for designers and artists as an entrepreneur’s sending out clowns and calliope to usher in his three-ring circus. “Critics want to tell you that this kind of thing develops out of collage or happenings or the values of action painting,” remarks Atkins, “but we’re just trying to use our training to create a situation to counter the waste of the human situation.” And Keith Albarn echoes this refreshing notion of organic process rather than cerebral second-guessing. “We hope people will grasp the more esoteric implications of what we’re doing,” he says, “but we prefer to theorize after the event.”

Museum With No Collection

While one can artificially bend most manifestations of the arts to conform to an environmental interpretation, the newly quartered Institute of Contemporary Arts in London is obviously an example of a museum that concentrates on presenting events and exploring environments as much as , if not more than, exhibiting art objects. It is the most conspicuously aggressive “modern” art center readily accessible to a wide public, and its hefty yearly grant from the London Arts Council moved one art critic, not without double-edged irony, to dub the ICA “the most lavishly subsidized centre in England for cultural trail-blazing.” Significantly, the ICA has no permanent collection, though artists have frequently donated works for sale to benefit the Institute.

While its blazes may be abstract and its trails meandering, the ICA has a reputation for pioneering. Founded in 1947 under Sir Roland Penrose and Sir Herbert Read and other artists, it has promoted Graham Sutherland, Victor Pasmore, Henry Moore, Max Ernst, Francis Bacon, Mark Tobey, Asger Jorn, Stanley Wm. Hayter, Sidney Nolan and many other artists since its inception. For years, it was housed in a dowdy, walk-up gallery on Dover Street. Now it resides in a somewhat clinically refurbished interior in Nash House, a huge, slightly peeling Regency mansion at the foot of the Duke of York steps on Pall Mall. The late Sir Herbert was its president; Sir Roland is ICA chairman. In his words, ICA’s aim is “to create a centre which can unite the arts” as well as “to bring in not only the other arts but also science, education, planning and industrial design.” The cybernetic art show scheduled for next month inclines one to feel that Sir Roland’s comprehensive mosaic of aspirations, only slightly less inclusive than MacLuhan’s preoccupations, is being implemented.

“Scientific Theatre”

Nothing could please ICA director Michael Kustow more. At 29, the bearded, bumptious and scrupulously articulate Kustow is all for getting into the mainstream of the environmental swim. He has organized a kind of Catherine-wheel series of events for ICA—everything from Vietnam read-ins and anti-American newsreels to ICA-sponsored “scenes” and happenings such as New York’s Bread and Puppet Theater or “Midsummer High” (“a large-scale anti-boredom device”) to weekend whing-dings at Hyde Park and Nash House featuring such staid instrumentalists as The Pink Floyd, Tyrannosaurus Rex, the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, Junior’s Eyes and Plastic Dream Machine. These presentations represent the lighter side of Kustow’s preoccupations. He envisions a new definition for the word “exhibit” at ICA and forsees a form of “scientific theatre, reflecting our technological environment, expressed in exhibitions using multimedia equipment—films, tapes and live performances—to get across—or explore—the relationship today between man and the machine.” In fact, Kustow told another reporter, “I think of this place as much more a television studio than a gallery.” He has even toyed with the idea of promoting ICA via closed-circuit television in Trafalgar Square and Charing Cross Station and has been dickering with the Beatles’ merchandising company, “Apple,” concerning plans to tour ICA shows in the Beatles’ projected chain of “Sgt. Pepper” clubs. MacLuhan might like that.

Swinging, But Is It Art?

The future of the ICA strikes one as swinging, all right, but it raises questions about just what art—and art museums—are today. Anything you can get away with? Whatever you can sell? There’s little doubt that in today’s relatively affluent, leisure society, people are so hungry for novelty and entertainment, they will leap for something that has the supplementary social cachet of being cultural. For all its futuristic bluster, however, the ICA’s inaugural show in its new house was anything but oracular. Entitled “The Obsessive Image 1960-1968,” it presented a careful, diplomatic blend of the old and the near-new—from Picasso, Balthus, Magritte and Miro to David Hockney, Allen Jones, Roy Lichtenstein, Eduardo Paolozzi and Andy Warhol. Most of the Americans would have been old stuff to a Yew York visitor, and many of the younger British painters and sculptors as well.

César's Towering Puce in Paris -- Thumbing his Nose at Traditional Art

There were some curious and moving juxtapositions, however. In one corner, a 35-inch proto-phallic thumb in polystyrene by French sculptuor César Baldaccini (mindful of the traditional artist measuring perspective height by thumb-on-brush) needed only a connected nose to make the ultimate comment on Robert Malaval’s polyester set of gams topped by what might have been whipped cream, looking like half a Frank Gallo girl next to Martial Raysse’s parody of Prud’Homme, a winged, cherubic hippie holding a pink, neon heart as he massages his bland love-object’s bosom.

The suave, the savage, the sexy and the sepulchral were motifs that dominated “The Obsessive Image,” from Francis Bacon’s boxed paranoiacs; Richard Linder’s leather-trussed torsoes; Niki de Saint-Phalle’s zany, brightly ballooning “Clarice” to Bruce Conner’s mouldering “Rose-for-Emily” figure on a crapulous couch, Jean Ipoustéguy’s male figure crashing impatiently through a swinging door or Giacometti’s movingly attenuated female nude.

Traditional though the ICA’s first show might have been, for London—which Kustow asserts is “much more gentlemanly an art scene than America”—it was a singular event, drawing only one really negative review. While it was composed of a number of Americans (and the American scene pervaded beyond these numbers), it conveyed the impression not of a British art exhibit, but of an international roundup of like-minded artists. Its English audience, which looked like one from the Museum of Modern Art (only the accent was different), was snowed by Andy Warhol’s eight-hour continuous movie-run of “Sleep” and the film selections of “Nine Evenings: Theater & Engineering” which were screened at the show alongside some of the more “pop” entries, epitomized perhaps by Paul Thek’s pinkly mausoleumed “Death of a Hippy,” a cast of the 34-year-old artist (price 4,000 pounds) in life-size with his own hair comprising the effigy’s haircut and scruffy mustache—a laborious piece which a quick visit to Madam Tussaud’s would put into correct perspective.

But the environmental itch of ICA was visible even in its “Obsessive Image” show. As one entered the long, white-painted gallery (which the RAF originally wanted for an airplane museum), the first art work one ran into was Jean Ipousteguy’s man crashing through the swinging door. He comes at you in what seems a blinding rush; as you face the exhibit, he looks as if he can’t wait to crash these doors of perception and cleanse them a bit more precipitously than you might wish. He reminded me of Boccioni’s running man evolving into space—hurtling into an environment of noise and speed with open arms, impatient to be free of common restrictions, ready for anything, confident, accepting; yet, for all the world, possessing that multi-skilled quality of the young man who is good at everything, including doing nothing well.

Postscript: A Bring-Your-Own Environment

Preoccupied in London with created environments, I stumbled into a significant one almost by accident—that solid, tourist standby Madam Tussaud’s Wax Museum. Madam and her mignons must be working overtime, for the museum is so up-to-date it already is exhibiting Prime Minister Wilson’s entire cabinet, the Tory Shadow cabinet, the Beatles, Twiggy and even perennials such an Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, fending off photographers, as usual. In the hall where history’s heads of state are ranked like a receiving line designed to give a shaky diplomat nightmares, there is an odd mixture of wit and reverence. Deep in one far corner, back behind Africa’s other political luminaries stands Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith with fists slightly clenched, partly obscured, like a hesitant party-crasher, by a folding screen . A black wreath leans against the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s left leg. Standing easy next to a stiff John F. Kennedy, former astronaut John Glenn Jr., his snub-nosed face lit by an ingenuous grin, is one of the liveliest effigies from any angle. President Johnson, no likeness from face-on but good in profile, bulks large to Kennedy’s left—in a suit that looks cut by Khrushchev’s tailor. Unfortunately, Dwight D. Eisenhower looks truly stuffed and ready for installation in the Smithsonian.

But the incredible realism of most of the figures produces its eerie effect: despite what the viewer knows, the eye registers human likeness and the mind weirdly assigns movement to the lifeless wax. Harold Macmillan, basset-eyed, bored, nods imperceptibly; a sly smile compounded of public presence and secret knowledge plays on Jomo Kenyatta’s craggy features; Harold Wilson, egregiously erect in his chair, seems to be thinking up a reasonable answer to the last nettlesome question from some Parliamentarian. It would need a physiologist or neurologist to exactly pinpoint the process, but I discovered in Madam Tussaud’s that the mind tends to “fill in” movement, to complete the illusion, almost as when one looks at op art or an optical illusion. The wax museum struck me as a place in which one helps produce the environment, contributing a whole mosaic of public history and media impressions stored in the memory files and triggered by the effigist’s modeling skill. You might stand and free-associate for hours in this silent but singularly un-lonely room. Yet in the “celebrity” section of the museum, where light works and sound collages surround Frank Sinatra, Twiggy and Robert F. Kennedy with a tatty implausibility, one is not inclined to contribute personally to the environment. In art, it is a little like the difference between standing in one of Dan Flavin’s neon-shimmering rooms and in a room containing a wildly whirling Nicholas Schoffer kinetic sculpture. Schoffer’s work overwhelms you; Flavin’s minimal, suggestive atmosphere coaxes senses into action.

The Merchandiser’s Mind-Massage

The mighty dollar as well as the Artist’s Muse is responsible for at least one other interesting “environment” in London, a mody clothes shop, beauty emporium and restaurant complex that occupies 20,000 square feet of floor space in London’s prestigious department store, Harrod’s. Called “Way In,” the blue-flocked, stage-lighted but discotheque-dim shop is a sleek, cool environment which cunningly caters to the young set’s taste and inclination as it gently seduces the pounds and shillings from their pockets with racks and racks of the latest ounces of fluffs and flounces the London birds call dresses. With the rock beat of the Top Thirty piped throughout from the record and book section, bevies of the dishiest dollies in dark-blue micro-smocks cut around through the hot columns of spotlighting helping the boys and girls pick out the grooviest threads for the weekend. Men’s socks come in pastel pinks and purples; there’s a men’s wig boutique where for 14 guineas, a Cockney-spouting file clerk can fit himself out in a Jimmie Hendrix fright-wig. Birds with silvery, ironed tresses cluster in front of big cosmetics tables, all piled like altars with the glossy, iridescent paraphernalia of beauty worship. Biba’s or Busstop, by comparison, look like Woolworth’s basement.

Like Harrod’s proper, where plush lounges, complete with color television, are provided for foot-weary customers, “Way In” is somewhere to spend the day—and great numbers of people, young and old, sit around the restaurant section, soaking up the scenes in the glimmer of blue Plexiglas and a psychedelicized light-show that goes on behind the Juice Bar, or squatting yoga-style on low-slung banquettes and munching layered chocolate-creme cake. It all looks like a surreal spread from some young girl’s fashion magazine: there are multiple mannequins of Twiggy, only slightly less articulate than the real thing, barely holding up a red bikini as she sits side-saddle on a Norton-Villiers motorcycle dazzling in chrome and Day-Glo paint finish. It is a scene calculated to warm the cockles of a Seventh Avenue garment tycoon’s heart.

Thus I sat pondering environments of art and commerce, noticing my wife kept a steady eye on me as I absently nibbled Rye Krisp and mused that, after all, the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London was still the best light-show in town, bar none.

Received in New York July 8, 1968.