MEMPHIS, Tenn. -In 1954 Elvis Presley came to be known as the King of Western Bop. He was the white boy who "sang black," the revolutionary, rockabilly cat whose body movements originated from the wild contortions of Southern preachers. He was lusty and evangelical, a combination of Valentino and Jesus.

If his soft face and body made men uneasy, striking them as feminine and offensive, those same physical attributes devastated women; Elvis's sexual appeal was his androgeny.

Elvis was a predatory male, who could sing "Baby Let's Play House" with a voice filled with lascivious suggestion. But he could also sing "Love Me Tender," and reveal a sweetness and a vulnerable heart, attributes more frequently associated with women. Elvis was as good as he was bad; he might do a girl wrong, but he would be so sorry. He radiated what e.e. cummings once called "an intense fragility" and from that tension came his power and sexuality.

To respond to him was to respond to sheer, raw sex. And had sexual obsession been an acceptable state of mind to those millions of his fans who were both Christian and working class, the response to him might not have progressed beyond it. But sexual obsession is not quite the style of God-fearing Christians, and so it seeks to dignify itself by emerging in more palatable guises, the way a man enamoured of a beautiful woman may assure himself that his ardor is based on her supreme fineness of character. And homelier virtues were not hard to locate in Elvis, who could have been invented by Horatio Alger, and remained ever humble, and claimed his success was due to Luck, and seemed to regard rock-and-roll riches solely as the means to make life easier for his mother. His virtues were initially invoked to justify passion, but they were such wonderfully compelling American virtues that they were swiftly transformed from justifications for passion to reasons for it.

Elisabeth Cronin is 32 years old. She has long, brown hair, clear pale skin, and a narrow, small-featured face. Like so many women who have pursued their fascination with Elvis regardless of what it may have cost them and others in money, comfort, and time, she combines a certain wistful romanticism with an iron will.

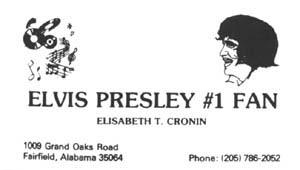

She lives in Fairfield, Alabama. She comes to Memphis twice each year where she dispenses calling cards printed with her name, address, and phone number, a poor likeness of Elvis's face, and the words ELVIS PRESLEY #1 FAN, a questionable claim.

She became intrigued with Elvis when she was nine. "My daddy had a theater in Atlanta. A drive-in theater. And I worked there, all seven of us kids did. He put us to work after school. So I just grew up with his songs and his music and with him, really." She was attracted to Elvis for a simple reason. "His looks. His looks are somethin' you just can't take your eyes off of."

On each trip to Memphis she brings several of her more than 50 Elvis scrapbooks. These are of particular interest to other fans, confirming, as they do, that Elisabeth has achieved the highest remaining ambition of Elvis fans: to be connected in some way to those who were connected to him. At the moment she is sitting in a Memphis coffee shop where she is the center of a rapt circle of the faithful, who envy her good fortune and can almost forgive it.

"Now see, here's me an' Mr. Presley. You know, Vernon. Elvis's daddy. That's him an' me at the fans reunion in Las Vegas, back in 78? A year before he died. See, he's got his arm around me, he sure does. An' here's me an' Sandy Miller. Vernon's girlfriend. She's just a sweetie, bless her. An' here's me an' Kathy Westmoreland. Who did Elvis's high voice singing. They say she sang so pretty at his funeral, bless her heart. An' here's the bedspread I made. See, it's all decals about Elvis. Took me two years, it sure did. Come by my house sometime," she says to no one in particular. "I got ten pictures of the Good Lord, one of my husband, and millions of Elvis."

She exaggerates. But just a little.

Elisabeth and Patrick Cronin live in a subdivision composed of two story homes, near the bleak, fume belching factories that scar the road leading southeast from Birmingham. A fine dwelling, it was financed through income derived from his job as an Alabama State Trooper, and hers in the meat department of Food World, a local supermarket.

The exterior of the house is rustic. Inside there is gold wallpaper embellished with silver trees. The livingroom couch is covered in plastic. The kitchen walls are covered with plates that have Jesus's face on them. Throughout the rest of the house this dual theme of the religious and the spectacularly secular is continued, a decorating scheme not unlike that of Graceland, and favored by the lower-middle-class Southerners who believe in God.

Elisabeth is a Baptist. She is, however, only vaguely aware of the Moral Majority or the Reverend Jerry Falwell. That is also true of all Elvis fans I have encountered in the first half of this year, and seems to suggest that the human psyche is capable of just one grand passion at a time.

Even as the most lavish Elvis collections go, hers is vast and astonishing, the result of expenditures of more than $15,000. As all fans do, she collects memorabilia at Elvis conventions that are held around the country, and which feature rows of tables laden with everything from Elvis cups to Elvis caps to Elvis lampshades.

She returned from the 1980 convention in New York City having spent $2,000 for statues and portraits of Elvis, including one that was painted on velvet. She came home from the 1979 convention in Kansas City with dozens of Elvis watches, necklaces, and pins, purchases totaling $1,500. She left the 1978 convention in Las Vegas with $3,000 in decanters and photographs including one of Graceland "when Elvis was asleep in it." During her visits to Memphis she has spent $5,000 at the various souvenir shops; the remaining $3,500 was used to purchase books, records and mail order items. Nonetheless, one of her most cherished possessions was obtained for free, from the electrician who used to work at Graceland, and is a small square of the green carpet that covered Elvis's bedroom floor before it was redecorated in brown.

In what was formerly the Cronin's dining room there are 12 statues of Elvis, and a model of the Tupelo, Mississippi house in which he was born. Two sideboards contain dozens of jumbled items, including an Elvis transistor radio and Elvis salt and pepper shakers. On the wall there is a picture of Elvis in heaven surrounded by fake red roses.

Patrick Cronin, a large, genial man, does not discourage such purchases or the obsession that underlies them. In this he differs from the husbands of many fans whose flat refusals to have their dens converted to shrines, or to let their wives join an Elvis fan club, or take trips to Elvis concerts have made divorce a distinct by-product of the Elvis phenomenon, even among those women whose religion frowns on it. Patrick Cronin is a rarity who remains sanguine when Elisabeth's friends come over to talk about Elvis, and even helps her with her collecting, perhaps understanding that no man is more secure in his marriage than he whose spouse is terminally fixated on another who is and always was perpetually unattainable.

Elisabeth offers coffee and an Elvis ashtray. Her son comes into the kitchen, a tall blond 16-year-old, child of the marriage that began when she was 13. "That was when my daddy sold the theater in Atlanta. And my family went to Lake Cross, Georgia, so he could drive for the overnight trucking company. And I was going to have to go with them. Joe, my husband. He had come to Atlanta to live with his brother, and I had just met him a couple months before. He was 15, working in a service station, an' $75-a-week back then was good money. So he called my daddy and asked could I marry him. I never did so good in school anyway. You can't when your mother has one baby after the other-I'm second, I got an older brother, the rest is all down under me-and you're taking care of them and working in a theater after school. But we lived with his mother, an' it was such a rough deal, an' during the sixty threes an' fours an' five I never ever heard a word about Elvis, not for three years there."

"That was back when President Kennedy was shot and 'The Fugitive' was on TV. I liked that, an' 'Peyton Place' an' all. I don't remember Kennedy too good, but I remember when he got killed because it came on the TV."

Elisabeth is just not in tune with the real world," Patrick interjects. "It's Elvis and that's it. She doesn't even like 'MASH.' How could anyone not like 'MASH'?" But he seems as amused by this failure of taste as he is at peace with the fact that it is far easier to embrace another's obsession than it is to change it.

Patrick and Elisabeth met in Birmingham in 1970. By then, she and her first husband had moved there from Atlanta. "We moved to Birmingham around "65, and I was living pretty much like a prisoner by then as far as seeing any Elvis movies. I didn't hardly see any since they didn't have em on TV like they do now. 'Course all that time I always kept up with Modern Screen magazine, anything like that, you know, that had Elvis in it, I sure did. I was real unhappy then. The only thing that got me through was thinking about Elvis."

She and her parents had lost contact. Finally they located her through a Baptist preacher. "Last time they heard from me I was in Atlanta, married and happy. " When she turned 16 she got her own apartment, but her husband followed her there. "I tried to get rid of him and get my own life back together. I got a job at Catfish King, this restaurant. Then I got my job in the meat department of Food World. That's when I had my son, but he lived with my mother 'til what? Three, four years ago. An' I didn't really get back with Elvis until 1972. I got to one of his '72 concerts, an' I got an 'I love you Elvis' banner there. That's how I started collecting. Back then, when you went to concerts they gave you a free Elvis calendar, they sure did.

"A lot of people might accuse me of idoling Elvis and worshipping him, or loving him more than God or more than my husband, but that's not true. He's my hobby. I love his songs, his music, his voice, his looks. And I believe the kind of person he was. I believe he's religious, he was such a religious fellow. Can't nobody ever tell me any different. I know he wasn't perfect 'cause none of us are perfect. I know I've been sick a year now: I fell and got hurt, and I have to take my medication to get up and go, so see I could be considered some sort of a dope user myself. So I can understand why Elvis had to take what he took, and it was all prescription, just like mine is too. I just won't ever believe anything bad about him and nobody will ever make me as long as I live. I just won't listen to anybody ever talk bad about him. He was too good. He gave his life to the fans."

"My goodness, who else do you know who performed as much as he performed. I just don't know of anything that's not perfect. He was honest, just as honest, and he's human, one of us. He was just a poor old country boy. I was raised country. An' he grew up an' made something of hisself. An' he didn't let it give him the big head or affect him in any way as being too good for everybody else. You see some of these stars, they just think they're it. There's nobody but me. But Elvis wasn't like that. He sure wasn't."

"Even though Elvis was as far away from me as the moon, you know, in distance, I still felt close to him."

"One thing I'm wonderin'. Do you know any fans who feel like I do? Are there any fans as big as me?"

The answer to her question is yes. In her stated role as the Number One Fan, Elisabeth Cronin is apt to encounter some competition from the millions of men and women whose cars proudly display the bumper sticker, "I'm the Number One Fan of the Man From Tennessee," for her tributes to Elvis perfectly replicate those given by other fans.

There, is just one exception-her lack of interest in John Kennedy. Typically, Elvis fans rhapsodize over JFK, focusing primarily on his looks, youth and glamor, a good gauge of both how well Kennedy understood the part show business plays in politics, and of the subsequent sexualization of the 35th President, who came across, Marshall McLuhan believed, as "a shy, young sheriff, " an image with some similarities to Elvis's.

Aside from that, what she says about Elvis adheres rigidly to statements of other fans, among whom a chief article of praise is that Elvis "gave his life to his fans" an absolutely pure act in their eyes, unsullied by his own needs, or monetary concerns or ambitions. Such tributes also invariably include appreciation to Elvis for having remained "one of us," a belief that validates and comforts, and one supported by his having lived primarily in Memphis, surrounded by high school friends, rather than becoming a part of the Hollywood social scene, as he could so easily have done. It is this last facet of Elvis's life that helps to explain why fans "felt close to him. "

To be Elvis Presley's Number One Fan, Elisabeth and literally millions of others have spent vast quantities of money, energy and time to connect in a variety of ways with the power embodied in Elvis. The price for connecting with that power is the price inevitably paid for obsession, which is that one's own self becomes lost, and one's own power becomes dissipated.

Yet Elvis fans are as adamant about connecting with Elvis's power as they are willing, even eager, to give their own power away, a syndrome composed of two parts that seem to be mutually exclusive but are actually one and the same.

The wish to connect with power is an expression of the desire to return to the protected childhood state. To give away one's power is to render oneself into childlike vulnerability and to thus become needful of parental protection. Therefore, in both the need to connect with power and to give one's power away there lies an illusory path back to childhood safety.

That sense of safety is what his fans found in Elvis when he was alive, for his fans viewed him not only as a lover but as a loving father. Then he died, and if there is a lament that seems appropriate for his fans it is the Irish verse: "We're sheep without a shepherd when the snow shuts out the sky. Why did you leave us? Why did you die?"

It is the need for a shepherd that explains in part why the Elvis phenomenon has persisted, why his fans are still his fans, and why they cannot let him die.