(ON THE KOBUK RIVER)-A fat chum salmon slid over the bottom of the Kobuk River, following tiny trails etched in the sand and leaving yet another trail to mark his passage. Nearby swam scores of other salmon, now silver but growing mottled pink as they left the ocean behind. Females fat with roe broke water and dove again. The shallows rippled in the long evening light as school after school surged upriver.

Three Eskimo boys eyed the current where the salmon passed. On a long sandbar behind them stood two white canvas wall tents. A fire burned slowly under a black iron pot of beaver stew. A dozen paces downwind stood long wooden racks heavy with cut and drying fish.

This is the middle of the vast Alaskan wilderness, north of the Arctic Circle and hundreds of air miles from Fairbanks or Anchorage. A map shows no roads, but charts instead huge parks, mineral deposits and five small Eskimo villages with a population of slightly more than a thousand. While America debates the fate of Alaska's wilderness, Eskimos live with that wilderness every day. They have lived with it for thousands of years and eventually will have to live with the decisions America makes. Even now, people lobby Congress to make subsistence hunting and fishing illegal. But here in fish camp, there is no talk of that.

The boys cast lines into the current, hoping to lure a fat sheefish to the bait. Across the channel, the floats on Florence Douglas' net dipped under water. A tired salmon twisted and turned, but the gill net tangled him even tighter. He struggled for hours, only to finally hang, exhausted, tail down.

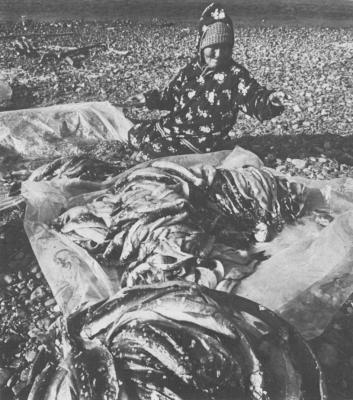

In the morning, after a breakfast of sourdough pancakes, oatmeal and coffee, Florence and her son, Eugene, loaded three washtubs into their flat-bottomed wooden boat. They motored a mile downstream to check a net there, then came back to check the one across the channel. With moves learned from years of experience, she pulled the net into the boat a few feet at a time. Still alive, the salmon struggled fiercely. A quick whack on the head ended it. Florence worked the net cord from around his sharp teeth, from out of the gills and over the fins, then tossed him in into the tub. This net yielded 23. All three nets she set yielded 90 salmon, a full day's work of cutting, washing and hanging.

Florence was not alone on the river. Up seven bends, her sister Margaret's camp was busy. Elizabeth Jackson and James Luke camped just beyond that. Further still, Vera Douglas, Daisy Tickett and Dora Johnson were surrounded with thousands of drying salmon and whitefish. Beyond were Nora Custer and Magdalene Lee and Laura Sun. Camps spread along the Kobuk River for miles, many in the same places Eskimos have camped for generations. Dozens of families caught thousands of fish, worth more thousands of dollars if they had to buy them. But the fish were not for sale.

Kobuk River Eskimos cannot drive to a supermarket for supper. The nearest stores-other than a few general stores-are 150 miles away by air. Out here hamburger is $3.00 a pound (at least). Bread is $2.00 a loaf. Fresh milk is unheard of. Feeding a family of eleven, like Florence does, could cost a fortune. So people earn their "wages" directly from the land.

As the salmon run ends, the caribou migration begins. Fresh meat replaces fresh fish on the table. When caribou season ends, dried fish, dried meat and frozen foods carry them through the winter. These Eskimos have always depended on the land for their survival. It is little different today.

The land and the Eskimo are the beginning and end of the food chain.

Now there are new obstacles. The National Park Service and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game have drafted regulations recognizing subsistence. But some worry that the regulations won't be flexible enough as game populations fluctuate or responsive enough as people's needs change. The new monuments are closed to sport hunting and so have forced hunters onto Eskimo land needed for subsistence.

Environmentalists feel outboard motors, snowmobiles and rifles spoil the wilderness experience. Some urge protection for all animals. "To kill for subsistence," the Committee for Humane Legislation said, "may indeed be part of our heritage, but it is a very ugly part that is... obsolete in today's modern world." CHL Director Jowanda Shelton elaborated. "If the Eskimos want to live like their forefathers, they should hunt as their forefathers."

National Park Service subsistence specialist Ray Bane replies, "Man can be a non-destructive part of the wilderness. He can be. There's a blanket of culture all over this area, an invisible blanket. When floaters float these rivers, they say, 'Look at this untouched land.'

"It's not untouched. It's just been touched gently. Why not let it continue?"