Art & Tech: A “Breather” of Anecdotes, Observations

Art & Tech: A “Breather” of Anecdotes, Observations

February 9, 1969

By S. K. Oberbeck

Mr. Oberbeck is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from Newsweek, Inc. This article may be published, with credit to S. K. Oberbeck and the Alicia Patterson Fund.

Lausanne, Switzerland—People ask “what are you doing over here?” I have two answers: 1) Writing about art. 2) Writing about art and technology. Answer #2 tends to make eyes wander and smiles tighten. “Hmm, that’s very interesting,” is a listener’s likely reply. Or: “Art and what!?” “Oh, you know,” I usually counter, “electronic music and artists who work with lights and motors and electric gear, painting with light. That kind of stuff.” It suffices. “Hmm, yes, quite right,” one English businessman replied—or, Distorted Feedback Loops in Disarray Worlds.

Such reactions are normal. For somewhere, a city is likely to be burning, a university administration building occupied, a border violated, a people starving or a helpless citizen shot or beaten in the street.

The week my wife and I sailed to Europe last March, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. One morning months later, we woke up in London to news that a second Kennedy had been shot. We took in news of riots, burnings, street battles, student uprisings, the explosions in the Middle East, the sorry toll in Vietnam. One fingered magazines and newspapers like a ticking bomb. The Paris spring was thick with manifs, paving stones, teargas, surging crowds. We were scheduled to go to Prague Aug. 18 (“we’re expecting you,” wrote a friend who lives near Hradčany Castle, “parking is no problem”), but decided to wait awhile in Germany. Two days later, we would have had to nose out a tank for a parking spot. Later, the debacle of the Democratic convention unfolded with its “Days of Rage” Chicago riots, and European news media had a field day with the sorry spectacle. Finally, we have come to expect daily riot and disorder columns as a regular feature of our newspapers, or an airline hijacking box as routine as the weather report.

Noble & Normal

I recall vividly two snatches of American Forces Network radio broadcast from these troubled times, one about the Czechoslovakian invasion, the other from the Democratic convention’s live coverage. There, a master of political hyperbole declaimed: “And now, ladies and gentlemen, I want to introduce to you one of the noblest men who has ever walked the earth...” (It was a New York representative, Mr. Fitzryan, if memory serves). Of post-invasion Czechoslovakia, an AFN newscaster loosed this headline: “Things are returning to normal again in Prague.” Normal? What is “normal” after invasion and occupation? These are the sort of utterances that, under the circumstances, can crack your faith in human communication.

What passed for “normal” in Prague

But even by these standards of normality or nobility, the news was exceedingly upsetting from all points of the globe. We fathomed the deeper meaning of that line from the Beatles’ song, “I read the news today, oh boy...” As if a destructive madness had seized most of the world, like a virus, sonic booms of purgative violence sounded around the hemisphere. Nobody seemed immune. In England last summer, a riot occurred among primary school children, who went rampaging because they had to wait too long for the serving of their “sweet” during a state-subsidized school lunch. Medical attention was required for several children and school personnel. The principal was struck with a knife. We could almost visualize the adolescent arm of England’s SDS giving revolutionary lectures in the school loos, as kids in short pants and knee socks rolled their joints in torn news photos of Danny the Red.

Media, The Moon

The two other events that stand out are the election of President Nixon and the flight around the moon. Richard Nixon, who had blown it in ‘60 on television, turned up suddenly as a subtle exploiter of cathode ray tube (which had ruined him in his run against JFK). He was elected despite the attacks of television and newspaper pundits who had previously tried to laugh off Gov. Ronald Reagen as a mere “movie star” or “image” manipulator. Yet something like $40-million was spent by major campaigners manipulating images via the media.

Finally, like a dose of much-needed spiritual medicine, those three not only wise but winsome men were making their Christmas pilgrimage around the moon, sending back the eerie picture of our own galaxial spaceship in its entirety, along with some particularly well-chosen explanatory notes from the book of Genesis. It did for us what it did for millions of Americans; it restored a sense of perspective.

Whistling Sculptures

Meanwhile, I had been writing about whistling sculptures, microscopic biological films, therapy chambers for autistic children, a forgotten Russian artist and real-time composing apparatus for electronic music--art and technology, to be sure, but not so intriguing, or compelling, as the dark fulminations of Black Panthers, a string of films all vying for the Priapic Oscar of “Most Sexually Explicit,” a campus rebel playing Fidel with the college president’s cigars, or the battles between the All Peoples Peace, Freedom & Justice Liberation Street Front and the Establishment “Gestapo” in Chicago, the media madness it generated or the government “report” that quickly followed.

“Squirting-Back”

These areas of incident and behavior will occupy the duration of these newsletters, though perhaps as obscurely at times as the notoriety of the Russian Constructivist, Tatlin, or in an approach and idiom as unfamiliar, and grating, as synthetic music. The shift in emphasis seems logical: one can hardly miss the connection today between art and politics or social affairs, especially in the areas of technology and communications media. Sometimes, it pops up in the most odd and wonderful ways.

This week, a news story reported that an Italian artist jumped out of a crowd and squirted France’s Culture Minister, Andre Malraux, with red paint at an official art function. Malraux wrestled his attacker’s paint container away and promptly squirted him back. In a society increasingly faced by confrontations and attacks, the squirting-back syndrome is bound to grow—though in some circles, it is bound to be deplored as a needless invitation to escalated violence. (We note that Japanese students recently “squirted-back” literally, with high-pressure fire hoses wrested from their proper handlers, at rebellious Leftwing students occupying a major Nipponese university, and finally dislodged them. California students, faced with picket lines when they try to attend classes, are learning the rudiments of “squirting-back”).

I take the liberty of using a personal voice—the “breather” of my title—partly to pay tribute to an assignment with the benevolent latitude of this one, and partly as therapeutic indulgence. Many journalists, I think, catch themselves writing as though every paragraph were preceded by the J. Arthur Rank man swinging at the gong—perhaps because journalists are conditioned to convey the impression that they are dealing with subjects of the utmost importance--or why would it occpuy the columns?

Because daily or weekly news media are obliged to invest with high import anything it handles. In cultural, critical areas, this tendency has already led to the “personality journalism” that almost eclipses its subject. Also, it legitamizes things. Or, as one artist remarked: “When a magazine or paper starts recognizing artists on a regular basis, it doesn’t just stop when a dry spell of talent hits. It hires a hot writer to make lousy artists sound important and interesting.”

In a world where journalists angle for reputations and the daily or weekly mill requires its grist, artists of minor talent are often picked up because the majors have been played out. You can’t go with empty space: “Sorry, no good art this week.” And that can help make minor talent into major. History is replete with such precendents: think of all the great, unknown artists or composers who never found a royal backer or critical promoter.

“Looking Backward”

Art is supposed to be a forward-looking adventure, especially if something like a “performance” cannot be possessed but only experienced. The two specific exhibits which strike me as the best indications of the A&T emphasis were the “Cybernetic Serendipity” show in London (SKO-1), which reached out with brash idealism for the shape of technology’s potential for the artist. The other show was “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age,” directed by Moderna Museet director Pontus Hulten at Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art. This comprehensive exhibit reached back, often with sentimental nostalgia, to put man’s stormy relationship with the mechanical in historical perspective. Yet, by its “Experiments in Art and Technology” competition, it also provided examples of things to come.

The two shows are convenient landmarks: “The Machine” showing where A&T came from and how it developed; and “Cybernetic Serendipity” indicating future directions and evolution.

From wheel to electronic circuit in two visits.

Dog Yummies

At the New York show, which incorporated everything from Da Vinci drawings, 18th century automata, Futurist paintings, a glistening Bugatti “Royale” (now, there was real paintwork!) and a touchingly decrepit version of one of Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Cars, was a work that typified the current A&T trends. It was a transparent plexi-glass sphere, 11 inches in diameter, containing a core of electronic parts, batteries, light and sound sensing devices and a motor—all mounted (gyroscopically, so to speak) on little rubber wheels that ran around the sphere’s inner surface. It was entitled: “Toy-Pet Plexi-Ball,” a joint E.A.T. product of appealing whimsy by artist Robin Parkinson and engineer Eric Martin, both in their early 20s. The Pet-Ball lived on a carpeted platform with raised sides, for it was essential to fence the creation in. Once removed from the black, furry “skin” cover into which it was zipped, it began to magically rove around its ken, in response to whistles, handclaps or changes in light, making a series of decisions built into its “brain.” At one point, a T-shirted attendant came over, remarked that the Pet-Ball “hasn’t been too active today for some reason,” and pounded a wooden sideboard, startling the sphere into a sudden leap of “frightened” movement. Watching the Pet-Ball roll around—not even merely on its own, but responding to its surroundings—I couldn’t help feeling that somebody was going to have to develop some kind of electronic dog Yummie.

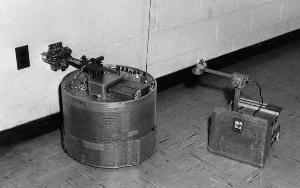

"Beast" robot plugs in at M.I.T

This clever exploration of the man-machine—or animal-machine—overlap had a singular precedent. Years ago, a similar, though more complex mobile automaton, was created by applied physicists at Johns Hopkins. It was dubbed, “The Beast.” Electronics authority Richard R. Landers has described it: “Shaped like a king-sized hat box with a retractable giraffe-like head, the device ‘thinks’ for itself. It also ‘eats’ when hungry, ‘plays’ when it feels good, ‘sleeps’ when tired, and ‘panics’ when it gets into trouble. When its tiny sensors, which follow along a wall’s surface, ‘feel’ for one of four available outlets, the machine’s head positions itself and two prongs lock into the socket. The robot feeds itself until its batteries are fully recharged and then wanders aimlessly in a playful mood until it is time to eat once more. It can survive on its own for almost a day in the halls. During this time it plugs into the electrical outlets about 25 times.”

Effervescent Humor

The sophisticated cybernetic aspects of both creations—one born of effervescent departmental hijinks of accomplished physicists and the other of the skill and sublime humor of two young collaborators—seems noteworthy and sanguine. We are told we live in a “technetronic” society, where the processes and concepts, not to mention the hardware, of electronics and technology shape the future towards which we race. They change, as well, the structure not only of society but also of our psyches. Since artists are traditionally supposed to be concerned with the real forces that transform our lives, it is natural—indeed logically imperative—that artists should be exploring our technological surroundings; and maybe giving the public a keener, more accessible insight into the effects and possibilities of science than even the field of science has by itself.

On the other hand, there exists the educational factor of technology as a whole, or, as MacLuhan asserts, the information environment that media create. No individual artist (or scientist), of course, could have dreamed up, and successfully created, the moon-shot of Christmas-time, which may well have induced more serious reflection on man’s place in his universe than much of the “art” supposedly revealing man to himself or providing him insights into his environment. (If I seem to be extracting undue mileage from our moon-shot, it is because the event was, in the highest and most exacting values and standards of “ART,” a truly artistic event, technological achievement, spiritual voyage. In fact, the recent terrestrial travels of Col. Frank Borman, judging from news reports, is proving to be something of an artistic achievement in the realm of diplomatic relations). Suffice to say, at any rate, that artists inclined towards the A&T trend will be working in an environment richer than that of any other generation of artists, including, perhaps, even the Renaissance.

A Confrontation

One theme that has been sounded in these reports is the commingling of art and politics, often under the banner of revolutionary justice. The first day I visited “The Machine” show in New York, a minor, though potentially major, incident occurred. A work by Greek-born electromagnetic artist Takis (on loan from its legitimate owner) had been exhibited against the artist’s express wishes. That afternoon, with a group of cohorts, Takis walked into the crowded gallery and, as his accomplices distracted the guards, removed his piece from its place. This involved whipping out a pair of wire-cutters and snipping free two suspended elements, picking up a heavy electro-magnet and escaping in a flurry of confusion and excitement out into the museum’s garden.

The press, of course, had been alerted. Museum officials, caught utterly unawares by the audacity of the “art-napping,” ran around like a kicked ant hill. One, obviously frustrated by the smugness of Takis’ supporters, blurted out they were lucky that they hadn’t been shot. “They shoot at people who try to take things at the Metropolitan Museum,” he said. “You’re just lucky this is the Museum of Modern Art.” When other MOMA personnel tried to get the artist and his merry men (who looked like a band of Cuban revolutionaries and medieval East European peasants) inside to discuss the matter, Takis & Company insisted on staying in open turf, out in plain sight—as if to suggest that once they were in the dank cellars of MOMA, they would fall victim to the truncheons and thumbscrews of a Fascist Art Establisment.

Cash & Carry?

But, of course, it was a serious little confrontation from both sides. The museum obviously could not countenance an artist who had sold his creation coming back and carrying it off again. They had a critical responsibility to its owner. On the other hand, manifestos handed out by Takis forces raised the point of what power an artist retained over his creation once it had left his hands. Did his relationship to his labor cease once he had his cash? Didn’t the museum’s refusal to allow him the option of not showing his work justify his cash and carry policy.

Aside from theatrics and a whole symbology of bogus values, the matter could have been boiled down to a simple question of contractual law. A clause could easily have provided for Takis’ wounded sensibility—provided his dealer could get a buyer to sign. But that was not the point. The point was, ho hum, another confrontation, another sally forth on the outmoded institution of private property and managerial elites (one manifesto suggested that anybody who wanted to should be allowed to exhibit at MOMA): Up the cash-nexus and a rousing cheer for the primacy of the artist—as long, that is, as he goes along with Marcuse and Mao. It was another example of the operational hypocrisy infesting not only politics but art now, in which legal means are discarded for emotional means. A minor power play, certainly, with a fairly tame adversary; but also an enticing precedent in an atmosphere where such forms of confrontation spread like a virus.

Presumably, though, they’ll think twice before trying it at the Met.

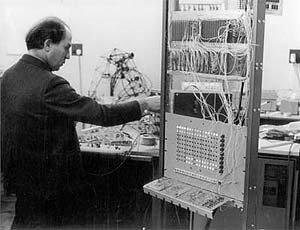

Edward Ihnatowicz programming his roving structure “Senster1”

The gentleman pictured above is not a mad inventor, but a sculptor who has been viciously bitten by the A&T bug. His studio, a converted garage in a scruffy London suburb, helps illustrate to what frightening lengths the A&T affliction can take an artist. Currently engaged in what might be called “motion studies” or “movement research,” he aims to produce an art—if it can be called that—which is non-tangible, in which the “hardware” is incidental to creation, and should be regarded as a system of research tools—say, like the system of tubes, flasks, retorts, etc. employed by a chemical analyst, which are devices that enable him to produce a certain chemical substance or determine its components.

“All living things are an expression of movement,” he says, “but to study movement you have to be able to control it. The only way to control movement today is electronically, so I thought I’d just jump in at the deep end.” He did, and while his aims and methods are over the head of the average art enthusiast, they are basic to important areas of science and technology (i.e., cybernetic control systems and computers). What he wishes to do is control movement by computer, programming structures he designs to execute whatever motion is within its ability. Then he hopes to sophisticate his apparatus to the point where, through feedback, computer and structure will carry on an open-ended dialogue of continual command-performance—in which the motions performed alter the computer’s commands and vice-versa. He has a long way to go.

From Pinter to Pistons

To these ends, however, Polish-born Edward Ihnatowicz has gone from the sort of portrait busts he has done for Harold Pinter, Sir Compton MacKenzie, Muriel Douglas-Home and jazz singer Cleo Laine to constructing elegant aluminum “vetebrae” which possesses the axial and planal movement potential of the crustacean’s real appendage, and is driven by double-acting hydraulic pistons. Not yet electronically connected to the computer he built himself, the ”claw” is controlled manually, as an operator controls the blade of a bulldozer. He plans a major kinetic construction to be called “Senster,’ for its feedback qualities.

Why a lobster’s claw? Why not? “Look at this,” Ihnatowicz said, picking up one of the real claws he keeps in a jar, “it’s really a beautiful mechanism.” And flexing it: “You can almost see the millions of years of evolution that went into the streamlining of that.” He starts to show me a scientific paper entitled “Nerve Impulse Patterns and Reflex Control in the Motor System of the Crayfish Claw,” then settles for another from West Hendon Hospital’s Centre for Muscle Substitutes, a prosthenic study.

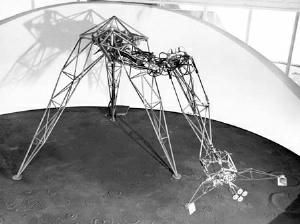

Ihnatowicz’s subsequent “Senster 1” at Philips-sponsored Evoluon Museum

Outfield Tracking System

Opaquely esoteric, all this; but it helps illustrate the scientific immersion many A&T-minded artists have undergone—and the science background many bring to their craft. The best of them work not so much in the area of science as in the area where science and human beings overlap—the man-machine interface, the realm of cross-over between human systems and electronic systems. I once heard a scientist remark that an outfielder going after a long fly ball was probably the most sophisticated missile-tracking system ever created. That is the sort of observation that seems to animate artists working with the products and concepts of science and technology, especially when they are not overwhelmed by the sudden discovery of these fields of human change.

Some Speculations

Boiling down priorities in the A&T field seems like an Augean Stable job, but some trends and speculations to be ventured are:

• Control will become a major factor of A&T art. The keystone of Ihnatowicz’s endeavors, for example, is set in the notion of control. One might be more satisfied watching the balletic movement of a George Rickey mobile, its flashing stainless steel lances swooping according to the wind that moves it and the limitations of its own pinioning. Or enjoy the witty, but crude, program of a Tinguely junk sculpture. But if art is really supposed to provide us with helpful insights, really supposed to clue us into what matters in our existence, then those kinetic creations which are rooted in the concept of control are the ones to watch—if only because one of technology’s major problem is that of control.

• There will be a shift in emphasis from content to concept. A primary aspect of A&T relates to the notion that technetronics have extended our senses, optics our vision, audio-systems our hearing, servo-mechanisms our physical reach (and sense of touch), etc. All these extensions are technological applications of physical or mathematical laws that exist as “verifiable” theory. Television, lasers, cybernetics, computers or the discoveries in the energy field that lead to moon-shots all spring from conceptions of the physical universe. All artists, by experimenting in these very areas, are depicting (or symbolizing) technological concepts that differentiate them from other artists. A painting of a computer, or electronic circuitry, serves to define the distance. A part of the modern art catechism is the equation: content = form, a formula that can be read in both directions. A&T artists add a new quantity to the formula, basic concepts that exist as physical laws, beyond the eye of the beholder—or the will of the creator.

• As Paul Cézanne and the Impressionists depicted in-field perceptual insights in painting that subsequently overpowered studio painters’ perceptual take-away notions, A&T artists will be recognized as the most advanced esthetic force to depict, in fact or metaphorically, the major physical laws that through technological application govern the lion’s share of our existence and development.

• The most important field in A&T is in the area of responsive artworks, which will grow. The most promising area has hardly been tapped: the creation which turns the “spectator” into “artist”—not electronic painting-by-number or the cybernetic kaleidoscope per se, but some extension of these processes, achieved by either various contained programs or an open-ended feedback response. Long-range sophistication of computer graphic techniques, or short-range advances in cinemagraphic equipment, providing new compositional or editing latitudes, may be the areas in which such devices develop.

• A question will arise over the actual “prophetic” qualities of artists in general. Are they really the leading edge of the avant-garde? Are they, in fact, the “early warning system” MacLuhan says they are? Are they moving from the “ivory tower” to the “control tower?” The spiral of scientific discovery and technological implementation of the last three decades has not been matched across a wide spectrum of art by a similar revolution in examining and interpreting the network of forces that are vastly restructuring our lives. In fact, much American art has suffered from a mechanical hangover, an inheritance of the last century, when artists and intellectuals, in the blunt words of Eric Hoffer, woke up to find their bourgeois brothers had taken the reins of power at the very moment artists and intellectuals were declaiming man’s cosmic insignificance. Infused with crisis post-war values, art has often resorted to the mechanical metaphor (“a cog in the machine”) to comment on a society already being changed by “technetronics.” Fighting “the machine”—or such traditional targets as the “bosses” or the “generals”—was an easier battle than locating the fugitive impulses that rocket through the ever more diffuse components of an electronicized society.

• The incidence of A&T trends, more oriented to cool research than to emotional values, seems a sanguine step in another direction.

• The trends toward events rather than objects, experiences rather than possession, involvement rather than effrontery, costly collaboration and more grandiose projects are likely to continue to proliferate—ironically following configurations of some of art’s formerly favorite targets—Big Business, Big Research, Big Government.

• Big Business will court the artist more as a matter of course than as a cultural contribution. Programs such as that started in England (Artists Placement Group) and America (Experiments in A&T) will increase. Last December, the Los Angeles County Museum announced an extensive A&T program, involving the placement, and subsidy, of 20 major European and American artists in some of the U.S.’s biggest industries (Larry Bell at Rand Corp., Robert Rauschenberg at Teledyne, Inc., Victor Vasarely at I.B.M., Jean Dubuffet at American Cement Corp., and, inevitably, Claes Oldenburg at Walt Disney Productions).

• A long shot: C. P. Snow will issue a revised edition of his famous “Two Cultures” speech, with an introduction by Bell Lab’s Billy Kluver.

And Last, But…

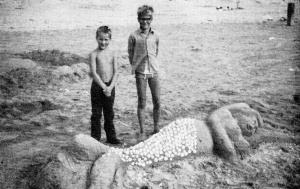

In the course of these months, I have seen many remarkable artworks I would have liked to include in my reports. One especially comes to mind: an untitled sculpture discovered (serendipity, but not cybernetic) on the coast of Holland. A sensitive, insightful work by two young Dutch (again, collaboration!) artists, who possess a vision that reaches far beyond their years. This sculpture was marked by an economy of detail, with deceptively simple modeling. Note the subtle contours of its primary forms and judicious use of indigenous materials, as well as the resonant mythic Greek overtones and the work’s direct relation to its environment. Also striking is the reclining figure’s blissful (almost ecstatic) expression, which cannot help remind us of the statue of St. Teresa in Bernini’s famous, little San Carlos Chapel…………blah blah, blah blah...blah, blah, blah.

Dutch Boys with their inspired beach creation

Received in New York February 14, 1969.