Art and Technology: “Cybernetic Serendipity”

Art and Technology: “Cybernetic Serendipity”

June 10, 1968

S. K. Oberbeck

Mr. Oberbeck is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner, on leave from Newsweek, Inc. This article may be published, with credit to S. K. Oberbeck and the Alicia Patterson Fund.

Nicholas's Schoffer's kinetic sculptures: Techtonic whizzers & whirligigs.

London—Several years ago, discussions of art and technology usually began with the handy citation of C. P. Snow’s famous “two cultures” assertion that art and science did not mix, that “literary culture,” traditionally the lodestone of the arts, was separated from “scientific culture” by a yawning gap. In the most modern arts today, the gap no longer yawns. It hardly exists.

Even a passing glance at what is happening to the visual and performing arts will confirm that the scene is anything but Snow-bound. In London, as in New York, art and science intertwine like sine-waves crisscrossing on the screen of an oscilloscope.

Wrap-Around Media

For manifestations of art and the materials and methods of science are visible everywhere in the wraparound media of daily living—in the ultra-hip television commercial or the multi-screen movie, in museums where kinetic constructions flash, sputter or gyrate; in urban parks and plazas where monumental, brightly colored sculptures in a variety of new materials gladden the everyday cityscape; in the frantic stroboscopic, psychedelic light shows of the pop music palaces, or in the mixed-media, post-Happenings theatricals now prevalent in London, New York or Tokyo.

Technology—the application of scientific principles or discoveries to practical problems—is affecting the arts and entertainments industry in a host of creative, strange and exciting ways. Consider, for example, that it is fostering a new breed of art objects whose electronicized innards may in five years wear out, or making possible the endless commercial duplication of a “unique,” artwork. Communications media—television, magazines, newspapers—have vastly widened and democratized the art audience, and quickly “use up” the artist’s latest innovation by broadcasting it world-wide in many cases.

Artists, of course, have always responded to the technology that springs from scientific discovery. The interaction between art and technology might be traced all the way back to the prehistoric cave painters, or to Leonardo Da Vinci’s efforts to reconcile artistic inspiration with mechanical invention, or to the impact on studio painting of putting pigments in portable tubes. Modern artists have even used technology to ridicule technology. Pop artists Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg put down the paintbrush for the silk-screen stencil and made salable, venerated art works of Brillo boxes, soup cans and everyday newspaper photos, using the images of the supermarket and the scandal-sheet to mock commercialist, sensation-seeking society. Jean Tinguely’s jitterbugging junk constructions, programmed for sound as well as movement, sarcastically comment on society’s mania for mechanistic efficiency by purposely breaking down or even destroying themselves.

Jean Tinguely's "Metamécanique" sculpture: Jitterbugging creative junk.

But these semi-didactic, almost literary applications of technology in Pop art are rapidly disappearing. They are being replaced by artistic endeavors that approach technology almost objectively, more in the spirit of scientific research than in the long traditional spirit of artists rooted in the literary humanism that carried over from the Industrial Revolution, who tended to regard mechanistic technology as automatically dehumanizing to the individual. Op art evolved almost purely, from the optical sciences and the insights they provided into the basic nature of visual perception—the difference between what the eye registers and what we “think” we see. Recognizing and exploiting those differences, Op artists set about producing unsettling visual displays that not only revealed eye-challenging perceptual discrepancies but also educated the public vision.

Air Force and Gymnastic Metal

Another fascinating aspect of the new changes in the arts—often made possible by technological sophistications—is the creation using such elemental forces as light, sound, movement, air or water. Luminal artist Earl Reiback, a nuclear engineer, uses polarized crystalline formations, nuclear radiation, holography and mechanically driven revolving lenses to achieve his psychedelically tinged projections of kinetic color and swirling movement that are sometimes programmed to be responsive to music. Britain’s John Healey combines lenses and mirrors to choreograph geometric abstractions of brilliantly colored light; one of his light systems was used to soothe patients in a London hospital’s maternity ward. Kinetic sculptor Len Lye mechanically and electronically programs strips and spangles of steel to do whirring gymnastics, while another artist, Larry Bell, uses an optical coating machine originally made for the U.S. Air Force to produce his delicately tinted glass boxes. Polish-born artist Edward Ihnatowicz sculpts articulated aluminum to mimic movement of a spine or lobster claw, works that react to their surroundings.

These are only random examples of a host of artists and a whole field of artistic activity which involves the methods and materials of technology. In this welter, it is not surprising to find artists interested in the latest technology has to offer--cybernetics, automation, holography. In early August, an art exhibit which draws its image from cybernetics is scheduled to open at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts, whose new quarters are an imposing Regency mansion on Pall Mall, just at the foot of the Duke of York steps. Called “Cybernetic Serendipity,” the show is the dream-child of assistant director Jasia Reichardt, a quick, smoothly professional art critic who first conceived the idea several years ago. It is slated as an international exhibit aimed at “exploring and demonstrating relationships between the arts and technology.”

Earl Reiback's "Vector Space" luminal kenesics: Symphony of color and light.

The idea of the pioneering venture, says Miss Reichardt, “is to show creative forms engendered by technology—and to present an area of activity which manifests artists’ involvement with science and the scientists’ involvement with the arts.” It will hopefully illustrate “the links between the random systems employed by artists, composers, dancers and poets and those involved in the use of cybernetic devices.”

The show has some impressive backing—much of it American. Though British business was sympathetic to the point of good wishes, it is I.B.M. that will provide six computers; and Calcomp, is also lending one. “Technical advisors,” a designation which one gathers means roughly “I’m interested and will do what I can ,” include John Cage and Iannis Xenakis, Gyorgy Kepes, British cybernetics authority Gordon Pask, Bell Telephone Laboratories, Scientific American and London’s New Scientist, Boeing Airplane Group, Sandia Corp., Honeywell, Westinghouse and many other experts and artists.

Divided into three sections, the exhibit will feature computer-generated graphics, films, music, choreography, verse and texts, as well an electronic or fully cybernated (operating on a true feedback loop system) art works, environmental groupings and remote control “robots”. Lectures and films (not computer-generated, one gathers), dealing with the relevance of computer technology to the humanities, arts and communications generally, will help enlighten confounded or bemused spectators of which there should be quite a few.

But here a qualifying word is in order, a major characteristic of the changing arts today is the new role of the spectator—a role Marshall MacLuhan says has ceased to exist in the electronic age. Though the average ICA visitor will doubtless still stand and watch, he will find his traditionally passive role as an aloof onlooker roundly challenged by the unsettling assembly of action-oriented art works and artistically seductive machines. A primary feature of many of the cybernized constructions is that they will react to—or interact with—those who come close enough to make their acquaintance.

The ICA may even have to replace the normal “Do Not Touch” signs with those reading “Please Do Not Upset the Sculptures.” Nicholas Schöffer’s “CYSP 1,” for instance, is regarded as the first cybernetic sculpture to possess autonomous movement—and something like a temper as well. It is a man-sized column of reflective vanes and painted panels which moves at two speeds and has axial and eccentric rotation. Even more eccentric, it is sensitive to sound, light and color, and launches into its whirling dervish act when confronted with the color blue, silence or darkness. But it becomes calmed in the presence of red, intense light or loud noises. British electronic sculptors Bruce Lacey and Edward Ihnatowicz will show creations that respond to their surroundings. Lacey, a wily artist who projects his zany, slapdash “actors” with a keen sense of humor, will introduce his “Owl,” a boxish array of photosensitive cells which generate the current that flaps his absurd bird’s wings (made of real feathers) while two spinning radiometers flash mischievously as “eyes.”

Ihnatowicz, a Polish-born artist who gave up sculpting portrait heads to work with computers and cybernetic systems, was recently commissioned by the giant Phillips electronics firm to produce a mobile sculpture for its continuous exhibition in Eindhoven, the Evoluon. At the ICA show, he will display something related to the Phillips commission—a construction that reacts, radar-like, to directional noise, turning towards the more vocal individuals a “head” of sound-gathering saucers and sensing devices on a flexible stack of cast aluminum “vertebrae” derived from the human spinal column for maximum movement and rotation. Tentatively, it will answer interlopers in its own mysterious vocal idiom.

Robot Love Affair

Dr. Gordon Pask plans life-size male and female robots, presumably programmed to portray some life-sized human instincts. Under the watchful eyes of all assembled, they will carry on an audio-visual amour by means of hoots, whistles and flashing lights (more Pask does not say). With their own whistles and flashlights, visitors will be able to affect the amatory extent of the robots’ love affair, which might give some therapeutic solace to fathers of recalcitrant, saucy British birds.

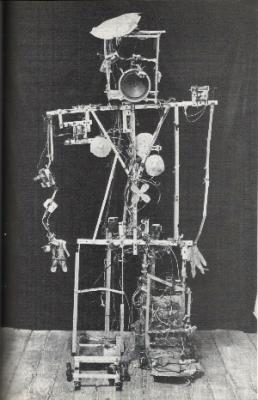

Nam June Paik's "Robot K" -Schizophrenic erector set.

Americans James Seawright and Nam June Paik are sending creations: Seawright his sophisticated, smoothly tooled “Scanner,” a 70-inch high suspended electronic mini-cosmos with a protruding photosensitive antenna which causes the flashing, clicking construction to rotate slowly according to changing light conditions. Paik is forwarding his now famously funny shuffling scarecrow of jumbled circuitry, “Robot K,” which looks like a schizophrenic’s erector set on a lost weekend.

Seawright’s more recent creations (and he is perhaps the finest young electronic sculptor at work in the U.S.) are meticulously crafted and employ circuitry, amplifiers, oscillators and digital computers. An electronic environmental work appeared several weeks ago in the Nelson-Atkins Gallery’s “Magic Theater” show in Kansas City, a kind of transistorized Stonehenge of twelve, black formica columns that scanned the circle they formed and reacted audibly to movement or lack of movement within them.

The young Alabaman, who says he spends about one day a week prowling for electronic components, is concerned with producing a family of sculptures that will interact with each other and alter their programs according to conditions surrounding them.

Paik, whose work with television media is well known, has prophesied that the cathode ray tube will replace canvas as an art medium much as collage superceded oil paints.

Drawing By Number

The cathode ray tube is instrumental in creating various forms of computer-generated art. The picture of Norbert Wiener, a major deity in the cybernetic pantheon, was produced by computer methods. It is a “digigram” translation of a 35-mm black and white slide of the famous author of “The Human Use of Human Beings” and is composed entirely of numbers. It is the work of H. Phillip Peterson of Control Data Corporation’s Digigraphic Laboratories in Burlington, Mass.

"Digigram" of Norbert Weiner: Cybernetics' "Big Daddy"

Roughly related to the half-tone dot structure of a newspaper illustration, the picture is composed of two-digit numbers which represent the density of color in the area they would occupy in the slide, based on a “gray scale” of 100 gradations. The higher the number, the darker the color. A Control Data Model 280 Digigraphic Scanner was used in conjunction with a Model 160 computer to scan the 35mm slide, averaging the color density in each of 100,000 “cell” areas. A Calcomp Model 564 plotter, driven on-line by a Control Data 3200 computer, was then used to plot the digits within the cells, which are .115 inch squares in the original plot.

And if all this sounds rather confusing, rest assured—even the computer’s nanosecond circuitry needs time to do its art work. The scanning and processing time on the Control Data 160 took only about four minutes. But the Calcomp 564 plotter took about 16 hours to complete its task. And Picasso works faster.

What, then, is the message in all this fancy electronic massage? Simply that “Cybernetic Serendipity” is a cogent local example of a promising trend catching on internationally among artists and technicians. They are carrying on a direct dialogue now, and exploring potentialities of new art forms in the skills and associative abilities each brings to this meeting of what Snow considered incompatible mind-sets. And their audience, at the ICA show, will be able to experience what many regard as a forbidding, anti-human technology in an atmosphere where twinkling lights, whirling tape spools and chatter of print-out from the computers may well create a mystical aura conducive not to anxiety but to interested investigation.

“Cybernetic Serendipity” promises to be an exciting and enlightening show , largely because of Miss Reichardt’s years of planning. As an illustration of how technology has affected artists and the art-technology exchange, it recalls the first major art-engineer liaison performance put on in New York in the Fall of 1966 called “Nine Evenings: Theater and Engineering.” This program of ten “events,” conceived by Happenings veterans and artists and choreographers active in earlier Judson Memorial Church presentations in New York, was staged in the 25th Armory (home of the “Fighting 69th” Regiment of Jimmy Cagney fame), the same site of the legendary, taste-tottering 1913 Armory Show of modern art, which similarly drew howls and hosannas.

Cultural Salad, Nicely Oiled

“Nine Evenings” was the joint inspiration of (primarily) Robert Rauschenberg and Swedish-born Bell Labs laser specialist “Billy” Kluver, who has long been keen on technological applications in the arts. The predominant theme was art-engineer collaboration (though artists came first on the billing, engineers got equal credit) and the roster of performers at first glance looked like a cultural tossed salad, nicely oiled with about $90,000 worth of support from private patrons such as national arts council chairman Roger L. Stevens, architect Philip Johnson and firms such an Bell, Westinghouse and Schweber Electronics.

By the time four “evenings” had passed, it was difficult to know just where to lay the credit—or blame. The audience—estimated at 1500 a night and representing the tout New York art world and the tutti frutti New York mod world—came expecting mind-boggling miracles as a result of publicity that all but promised to thoroughly cleanse our doorways to perception. But from the beginning, “Nine Evenings” had trouble finding the doorknob.

Five examples of events staged: Steve Paxton, aided by engineer Dick Wolff and various other technological gremlins, attempted to inflate a huge plastic labyrinth (including a 100-foot high polyethylene tower) for the audience members to walk through. But this effort ended with the helpers, hands over heads, supporting the long, limp labyrinth from inside—a London-Bridge-is-Falling-Down effect that occasioned many a snicker. Artist-choreographer Alex Hay, his body wired with devices amplifying his brain waves, breathing, heart-beat and eye movements, randomly laid out 100 numbered squares of flesh-colored cloth while his body processes thumped out an insider’s sonata. When he had finished, Rauschenberg and a sidekick picked up the cloths in correct numerical order, to an audible chorus of unstifled yawns.

Itinerant Yogis

There was a fanciful tennis game played by a couple with electrified racquets, the man’s producing a low-pitched pong as it contacted the ball, the woman’s a high ping. Each stroke also dimmed the lights a degree until the game was called on account of darkness, a condition parallel to the understanding of much of the audience. Dancer Yvonne Rainer conceived a piece in which leotarded dancers postured slowly on remote-controlled rolling blocks that carried them in random, meandering paths around the Armory floor like itinerant yogis.

And in the blow-thy-aural-faculties department, composer John Cage filled the towering, darkened dome of the Armory with an ear-curdling collage of synthesized noise from tapes and from everyday appliances (a blender, coffee grinder, fan, etc.) ranged on a table which he nimbly manipulated, striding back and forth in the ghostly glimmer like some cinematic Dr. Phibes. As the rumbling, crashing leit-motifs flooded the domed darkness, one had the feeling of being a beleaguered Jonah in the belly of a whale with powerfully audible indigestion.

Whatever its defects, and they were legion, “Nine Evenings” was a milestone of recognition that art and technology were trying to touch hands. Despite some bitter criticism, the event’s myth continues to grow and filmed portions were recently featured at the ICA’s premier exhibit in its new quarters.

Divested of its mantle of esthetic myth, however, it had obvious problems. One was an inherent difference between the ways artists and engineers thought and worked. In what might be called their technological “euphoria,” the artists seemed to make grandiose technical demands which their practical cohorts simply could not satisfy. They appeared, at times, to view the imposing array of electronic gear as endowed with magical qualities it just did not possess. The artists had spectacular conceptions to be staged, the engineers had blown fuses and wiring problems. But both found out a great deal about each other.

E.A.T., Inc.

Here, it should be mentioned that “Nine Evenings” evolved primarily from an organization pioneered by Rauschenberg and Kluver, E.A.T., Inc. (Experiments in Art and Technology) which was formed to familiarize the artist with the realities of technology while indulging the technician’s penchant to transcend mere practicalities of his discipline. EAT has consulting members such as Cage and Kepes and has enlisted support from I.B.M., A.T.&T., A.F.L.-C.I.O. It sponsors a variety of lectures and dialogues on subjects ranging from lasers and holography or polymers and acrylics to computer generated images or the physiology of sound and vision. It has grown rapidly, taking on correspondent groups in 35 cities in North America and Europe and was to have its first international conference this month in Manhattan.

In London, Barbara Latham, wife of painter John Latham, originated a somewhat similar concept in the Artists Placement Group, active in getting industry to retain artists to work in factories (which, as a matter of fact, is a more likely haunt of today’s artist than most museums). The APG notion is that artists will supposedly generate new ideas for industry, while gaining an organic knowledge of the true properties of manufactured materials and process. In the sense that new art forms often grow from the inherent nature of materials, the APG (which has an eight-member board and receives 1000 pounds annually from the Arts Council) may prove to be a rewarding venture.

New Generation

It might be interesting to speculate how long, in America at least, there will remain a real need for organizations such an EAT. It is a perfect example of how to bridge the “two cultures,” but as a new generation of artists comes along, one raised amid telecommunications, teaching machines, computerization, etc., we may well have already witnessed the grafting together of art and science. Today’s modern artist is a radical departure from that of ten years ago, or even five. He is as deeply involved in research, using the tools of science that apply, as in creation. And his researches, exemplified in “Cybernetic Serendipity” and “Nine Evenings,” are bound to change the parameters of the public sensibility. Apropos of a dance troupe’s mixed-media performance here several days ago, a radio critic commented that dance today is not what we usually call dance, nor music now what we are accustomed to calling music. The same is true of art. And this should occasion no special surprise: it is not the same world anymore either.

It seems a hopeful sign, then, that the current trend in the arts is towards an esthetic appreciation that takes note of society’s alteration, and towards new art forms forged from the pervasive technological forces that have radically reshaped our environment.

Now, don’t forget to turn on the sculpture. Or is it in the repair shop again?

Received in New York June 12, 1968.