My journey to the crossroads of race, faith and family in America: Tracing my ancestor’s footsteps

CANTON, Mississippi – Federal Union soldiers fought here in 1864, riding south from Memphis looking to ambush and kill rebel troops, and disrupt their supply lines. Moving swiftly on horseback, the Union soldiers slept on a bluff on the night before a surprise raid on a Confederate-held bridge. It was not a particularly notable engagement and never made the history books. It was just one of many sharp and lethal encounters that would eventually dismantle the Confederacy and destroy slavery.

What was extraordinary about this engagement is that the Union troops were ex-slaves – an all-volunteer “colored” regiment. And one of my ancestors, The Rev. George Warren Richardson, a Methodist circuit-riding preacher, was the white chaplain – and also a volunteer – to this black Union regiment.

Not long ago, I traveled to Mississippi to walk on the same ground where my ancestor and his soldiers slept on the night before the raid. I was brought to this place by his writing; I was especially moved by his journal description of the camp that night:

“The voice of prayer from so many at the same time, made the place seem wonderfully sacred. I said ‘Surely God is in this place.’ This circumstance impressed me deeply.”

I could not be sure if this was the exact spot that he had described. But all that I learned on that trip convinced me he was here, or in a place like it near here.

My journey to Mississippi was one of many trips I have made in the decade attempting to retrace my ancestor’s footsteps. Other trips took me to Tennessee, Illinois and Texas, and to the banks of the Sacramento River north of where I’ve lived much of my life in California. Remarkably, George Richardson wrote about all of these places in his handwritten journal that has come down through my family and to me.

On this particular spring day in Mississippi, I walked up a dirt road to a clearing where a local historian says that the black soldiers and their white officers camped the night before their raid. My ancestor never disclosed in his journal exactly where he was – they were just somewhere in Mississippi south of Holy Springs, searching for rebels. I was hoping to get a sense of what he might have seen that night before their skirmish with Confederate soldiers.

My journey on my ancestor’s path began in the summer of 1997. I had just finished promoting my book about Willie Brown, the powerful California politician who had risen from his roots as a poor African American in Texas, a project begun as an Alicia Patterson Foundation fellow. With the book finally behind me, I prepared to set forth on a life-changing venture to enter the Church Divinity School of the Pacific, the Episcopal seminary in Berkeley, California, and enter Orders as an Episcopal priest. I had been a newspaper reporter for 22 years, and making this transition was proving to be anything but simple or certain.

Sensing my struggle, my father, David Richardson, loaned me the handwritten journal of his grandfather’s grandfather, George Richardson, and suggested that I might want to read it before embarking upon my new vocation.

In our family, this somewhat dog-eared book was referred to simply as “The Journal,” and now it came to me. I had known of this journal since childhood and how it had been handed from father to son, and how, in fact, it was my father’s most cherished possession. The journal was written in a nineteenth-century notebook, and the years have not been kind to the binding or the paper. When I received it, the journal was held together with masking tape and the pages had turned yellow and brittle. Mostly it was written with a fountain pen, but some pages were written in hard-to-read pencil.

In all the years of seeing the journal on the bookshelf in my father’s study, and being told to retrieve it if the house ever burned, I knew very little of the extraordinary saga contained inside. No one spoke much about it; few in our family had actually read it though they knew of it. The journal was treated almost as if it contained some mysterious family secret, which in a way, it did, and not all in our family were necessarily in support of the work it described. Our ancestor had helped liberate African American slaves; as the decades unfolded into the twentieth century, that was not necessarily viewed as heroic by some of those who bore his name.

Knowing nothing of this, I must confess I was a bit puzzled that my father would loan me the journal before I entered seminary. The summer weeks began to slip away and I did not open it. I had much to do to get ready for seminary life, and truthfully I was having second thoughts about going. On the weekend before the academic year started, I was not even sure I would show up.

That was the weekend I opened the pages of the journal.

I ended up spending the entire weekend reading George Richardson’s journal. I did little else, and found myself filling my own notebook with copious notes. I knew then I would have to go to the places he wrote about.

George was born in rural New York, and as a young man was much a part of the settling of the West. George and his family were embedded in the anti-slavery fervor of their time, and aided the Underground Railroad. He served in the Civil War as the chaplain to the 7th U.S. Colored Artillery Regiment, the remnant of the most martyred unit of the war. His story became even richer after the war as he and his wife and children founded a college for African Americans in Texas, Samuel Huston College, overcoming terrific obstacles and facing down opposition from the Ku Klux Klan.

Late in life, George was a chaplain to cowboys on the Texas Panhandle, and then moved to California, Oregon and Idaho to start new churches. Throughout his life he stood for the ideals of liberty and justice for all, founded on the rock of his faith. He died peacefully at home in Denver at the age of 87. He lived long enough to see the college he founded in Texas prosper at the dawn of the twentieth-century, and to see two of his children take up the cause of his life among the ex-slaves.

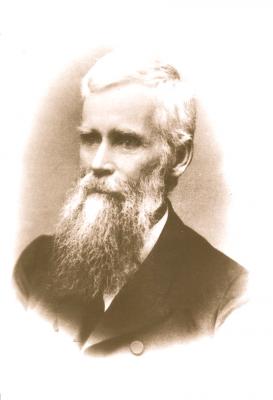

After closing the journal, I headed off to seminary and its struggles, and I began to think of my new life in ministry as joining the family business. I could not help but feel that George was present somehow, nudging me along, telling me to stiffen my spine and get on with the Lord’s work. In the years since, I’ve talked extensively with my aunt Madge Richardson Walsh, among a handful of women from her generation to earn an advanced degree in anthropology from the University of California, Berkeley. She is among the few in the family who has read the journal. Years ago, she typed out a copy and indexed it, annotating the events recounted in the journal’s pages. She also gave me a photograph of George, which I now keep on my desk.

My aunt gave me another priceless treasure: a small notebook wherein George had recorded the outlines of his sermons and other notable events including the marriages of ex-slaves. She also gave me copies of pages from a diary written by George's oldest son, Owen, shedding more light on these events. To her I owe a great debt of thanks for her insights and diligence in preserving these family documents.

I was ordained in 2000, and I’ve gone into parish ministry serving congregations in Sacramento, Berkeley, and now in Charlottesville, Virginia.

My father, David Richardson, died in January 2004. My father’s death prompted me to renew my interest in George's life as part of my own rediscovery of my father’s life and his values. I resolved to retrace some of our ancestor’s steps for myself – not just to read the journal, but also to walk the ground our ancestor walked.

My first trip, in April 2004, brought me to Nashville and Memphis, where George was posted in the Civil War. Next I went to Texas where, to my amazement, I discovered I needed to go back to places where I had researched my book about Willie Brown, who had grown up in segregated East Texas. Unknown to me at the time I was working on that book, a century earlier my ancestor had brought Methodism into the Texas communities of former slaves, building schools and churches and preaching about temperance in the same places where Willie Brown would later grow up. A pivotal figure was a courageous black Methodist pastor named Jeremiah Webster, who lived near where Brown would be born a half-century later. Webster became George’s partner in ministry in Texas.

Later that summer, my wife, Lori, and I found George’s home in Galena, Illinois, where he and his family maintained a station on the “Underground Railroad” in the grim 1850s leading to the Civil War. Galena was also the home of Ulysses S. Grant, whose parents were members of George’s church. There is no mention about whether George met the illustrious general but he certainly knew his parents. My journey continued in 2005 when it was one of the great honors of my life to be invited to give the commencement invocation at Huston-Tillotson University in Austin – the historically black college George and his family had founded. More trips would follow.

Please allow me tell you about my journey of discovery and the life of this remarkable man of faith, The Rev. George Richardson.

Horse and hack

George Warren Richardson was born in Erie County, New York, in 1824. His bright red hair sparked much teasing as a child. He was the son of a blacksmith who was also a licensed preacher in the Free Will Baptist Church. The Free Will Baptists were known for two things: their strict piety and their ardent opposition to slavery. In our own era of culture wars, we do well to recall that the anti-slavery cause was fueled largely by the evangelical fervor of the early nineteenth-century that became known as the “Second Great Awakening.” The greatest preacher of the age, Henry Ward Beecher, denounced slavery, and his daughter, Harriett Beecher Stowe, wrote what may be the most influential novel in American history: Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The political movement that ultimately ended slavery grew from the Second Great Awakening, and that movement spawned the spectacular expansion of the Methodists into the single largest church of nineteenth-century America. George and his family were deeply a part of that.

As a young man, George bridled under the rigidity of the Free Will Baptists, but the Baptists’ commitment to abolitionism struck a chord deep within him. His passion for the anti-slavery cause became the focus of his life, and he found his spiritual home with the Methodists. For many men and women of the age, including George Richardson and his future wife, Caroline, their religious awakening and Christian fervor were inextricably bound together with their commitment to the cause of ending slavery. They saw no dichotomy between their politics and their religion.

George's father died when George was twelve; he and his mother and siblings managed their family farm as best they could, which turned out to be not well. A few days before George's twenty-first birthday, his right arm was mangled in a farming accident, and his forearm had to be amputated. He survived his injury, a miracle of the time, and later wrote that it was the greatest blessing of his life because it got him off the farm. But it also forced the family to sell the farm and leave New York.

George came west to Wisconsin looking for opportunity – and following a young woman whose family also had migrated from Erie County. Caroline Amelia Fay was George’s major reason for his coming to Wisconsin. Her family was deeply Methodist and deeply committed to ending slavery. In Milwaukee, George joined a Methodist colony, perhaps at first only with the motive of impressing her.

Her family had been neighbors with his in Erie County, New York. She had defended him from the taunts of classmates teasing him about his red hair. They forged an extraordinary partnership in marriage and ministry. They would have four sons and two daughters (one daughter died as a baby); their second son, David Fay Richardson was the father of David Russell Richardson (whose first and middle names were later inverted by his parents), who was the father of David Cutting Richardson, who was my father (and my middle name, no surprise, is David). All of those Richardson men, starting with George, took to signing their names with their first initials and last name.

George went to Allegheny College in 1847 and 1849, and proposed marriage to Caroline. She apparently hesitated before writing him a letter accepting his proposal. Her letter is among a handful of her items preserved by my aunt, and gives a glimpse of how marrying George was an act of her own faith:

I have been undecided, and now I cannot express my self as I could wish. Strongly attached to friends & home it seem difficult for me, to resign these loved scenes, perhaps forever. But why should I hesitate, for in you I trust I shall find a guide & protector that is worth of all confidence that I can bestow. Trusting to your superior knowledge and judgment, & believing that you will do what you feel to be right in all things that concern you, I feel to adopt the practiced language of Ruth.

Where thou goest, I will go with thee,

Where thou livest, there will my home be,

Thy cares and thy joys, alike I will share.

Our voices oft, shall be mingled in prayer.

George was licensed as a Methodist preacher in 1850, and he married Caroline on May 16, 1851. He launched his preaching career as a Methodist circuit rider covering a desolate, lightly populated frontier territory in Wisconsin, northern Illinois and Minnesota. Like other Methodist preachers of the era, George would ride from town to town by horseback, or sometimes by horse and “hack” (buggy). In each town, he would conduct the “classes” that grew into churches, following the method of the English Anglicans, John and Charles Wesley. Their tactics for building a church – their “method” – became known as “Methodism.”

Following the Wesleyan system, George would be assigned for a one-year stint as pastor to a church before the Methodist elders required him to move on to the next. He and his family supported themselves by tending farm, either their own or a farm on loan from the parish. The Methodists did not believe their pastors should stay in any single congregation for more than a year or two at the most, hence the life of a Methodist preacher and his family was never long settled.

While the method proved ingenious for building churches, it proved to be a major strain on family life and the wellbeing of pastors. George’s mentor, The Rev. Chauncey Hobart, was a major figure of Methodism in the upper Midwest, and he looked after George and his family at crucial moments in their lives. Decades later, Hobart would bury Caroline Fay Richardson in his Minnesota family plot.

The life of a Methodist circuit preacher in mid-nineteenth-century was mostly lived on horseback, and at no small risk to body and health. Life on horseback was dangerous. Horses fell through ice, and on at least one occasion George became disoriented in the Minnesota woods in winter. A Chippewa Indian hunter who found him wandering led him to safety. On another circuit ride, George’s horse fell through ice, and he proclaimed it a miracle that he and the horse survived.

By living in the saddle, the Methodist circuit riders developed an evangelical formula perfectly suited for success on the American frontier. The preachers covered vast territories, planting churches as they went, never staying long, and turning over control to the local people. By the dawn of the twentieth-century, the Methodists grew from a small offshoot of the English Anglicans into the largest Christian denomination in the United States. George Richardson and his family were among those who had a stake in that success.

As partners in life and in faith, George and Caroline took risks large and small, enduring frontier depravations, illnesses, accidents, financial ruin, vigilantes, and war. Their faith carried them through the death of children and loved ones, the loss of close friends, and faith gave them their cause for living. Medical care, when available, was primitive at best, and both dodged death more than once from infections, accidents and severe injuries. They endured years spent apart for the greater cause, with George riding his circuit while Caroline raised funds and ran schools, farm and household. Domestic comfort, when it came, was fleeting.

Kitty the slave

Three years into their marriage, and George wearied of life on horseback. He and Caroline yearned for a stable family life, and so moved to Galena, Illinois, the leading city of northern Illinois at the time. George found a teaching job, and by then the couple had one son, George Owen. Their family would soon grow.

It is hard to see now, but in the years before the dominance of railroads, Galena was the transportation hub of the upper Mississippi Valley. In fact, Galena was larger and more important than Chicago. Near Galena were lead mines, and thus Galena grew as the shipping center for ore and other goods down the great river. Galena was a Union town, and by one measure, the most Yankee town in all of America. Galena produced no fewer than nine Union generals, most notably, Ulysses S. Grant.

The most important figures of nineteenth-century America came to Galena: Frederick Douglas, the ex-slave prophet of abolitionism, spoke eloquently for the anti-slavery cause in Galena; Abraham Lincoln stumped for president in Galena in 1860, and George would proudly cast his vote for Lincoln – the only vote he ever mentioned making.

In Galena in 1852, George and Caroline became a link on the Underground Railroad, spiriting an escaped slave, Kitty, out of town disguised as a man. This may have been their only involvement in the Underground Railroad, although from George’s description, he and Caroline knew precisely what to do, who to contact and how to evade detection. They were either very well rehearsed or more experienced than he let on in his journal. He never revealed the names of his co-conspirators, or said how he had become involved with them.

Kitty had come to Galena as the possession of a Southern white man on business. Abolitionists arranged for her escape, and brought Kitty to the Richardson’s’ home. George gives no hint on how he came to being in on the plot, but he and Caroline sprung into action once Kitty arrived on their doorstep.

“We only knew she was a human being panting for freedom,” George wrote. At the time, Caroline was pregnant with their second son, David, who would become my father’s grandfather.

My wife and I visited Galena in August 2004, and we found the town charming, and wonderfully well preserved from its pre-Civil War days. The archivist at the public library, Steve Repp, found George Richardson listed in the city directory, and showed us on a map where his house still stood. Repp excitedly told us that he had never been able to prove the existence of the Underground Railroad in Galena until we showed him George’s journal entry.

The city directory gave no address, listing the Richardsons as occupying a house on Dodge Street, near Hill Street. A short hike later we found three plain brick houses on a hill; one of them had been the Richardson home.

As we continued to walk around Galena, we could imagine the difficulty of spiriting Kitty out of town unseen. Caroline dressed her in men’s clothing, and George took her in his wagon through the center of Galena before turning north to a secret rendezvous point where he handed her off to the next station in the Underground Railroad.

George noted in his journal that he had violated the law, the infamous Fugitive Slave Act that forced northerners to catch slaves against their will. He noted that he could have gone to prison had he been caught. But George figured no one would suspect a one-armed pastor of such an act. He felt that he and Caroline had struck a blow for freedom that day. There was no turning back; George and his family now were on a road that would change many lives in many places.

George and Caroline grew frustrated with teaching in Galena, finding the town too rough to rear a family. George was physically assaulted by one of his students; though having only one useful arm, George pinned his assailant until lawmen arrived. Eventually the Richardsons gave up on Galena and returned to Minnesota, where he took up the life of a circuit-riding preacher again, enduring harsh winters in the saddle and relentless illnesses to keep up with his flocks on Sundays.

What Caroline may have thought is not recorded. On their tenth wedding anniversary, in 1861, she wrote a poem to George, preserved in a scrapbook in my aunt’s papers. Caroline’s handwritten poem begins by remembering their marriage began in the “sweet and budding time.”

Then the years marched onward,

And though we’ve sometimes trod the sand With sore and bleeding feet I’ve ever found thy firm strong hand Stretched forth to guide and keep

Ten years hath wrought its change sore In many a household hand With us hath grown loves precious store In closings heart and hand.

As the Civil War erupted, George became increasingly restless and felt isolated as an itinerant pastor in Minnesota. The sidelines did not suit him.

Two years into the war, the Minnesota conference of the Methodist church approved a resolution supporting the emancipation of slaves and the Union cause. The Methodist resolution had no practical effect on slavery, but it had one immediate impact: At the age of 39, George resolved that he had to get into the war – somehow, somewhere.

“Such patriotic speeches and resolutions kindled my patriotism to a white heat,” he wrote. “I knew of none of my relations that bore the family name that were in the war. I was ashamed to have my children feel that none of their relatives helped to save the Union.”

Fort Pickering

In January 1864, found his way into the Civil War, the cause and test of his generation. George was among a group of pastors appointed by President Lincoln to a commission dispatched to Tennessee to prepare a report on the morale of Union troops. The Tennessee theater was stage to some of the most savage fighting of the war, with battles recording the highest casualty rates in American history, including Shiloh, where 20,000 soldiers were killed and wounded in two days near Memphis, and Stones River where both sides fought to exhaustion near Nashville.

The Northern pastors ended up doing a good deal more than writing a report. George went to a hospital in Murfreesboro, outside of Nashville, to minister to wounded and dying Union troops. Along the way they found the parched bones of soldiers who had died months earlier at Stones River. As gruesome as these battles were, he was awestruck by something else: the sight of ex-slaves crossing the battle lines to enlist as Union soldiers. “I decided then and there to take a place as a chaplain of a Negro Regiment if such an opportunity offered.”

He had scarcely seen a black person before. Until then, his only recorded direct encounter with an African American was with Kitty, the escaped slave in Galena. What had been a brief episode then would now consume the rest of his life, though he did not yet know it.

In April 1864, George received his commission and was posted to the 7th U.S. Colored Artillery Regiment at Fort Pickering, Tennessee. The regiment had been formed from the survivors of the 6th U.S. Colored, possibly the most martyred unit of the Civil War. A month before George's arrival, a contingent of the 6th had been posted at Fort Pillow, north of Memphis, along the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. The fort was indefensible and, tragically, the Union defenders were poorly led. When Confederates captured Fort Pillow, the surviving black Union troops were summarily executed. Lt. General Nathan Bedford Forrest, a brutal self-made millionaire from the slave trade, led the Confederates.

The war crimes at Fort Pillow are considered by some historians as the worst of the Civil War, and those events remain a flash point of controversy to this day in Tennessee. The atrocity so outraged President Lincoln and Union General Grant that prisoner exchanges between the two armies were suspended for the remainder of the war. The surviving remnant of the 6th was reformed as the 7th U.S. Colored, and George joined it in Memphis.

Capturing Forrest became a holy cause for George’s regiment. Yet though the regiment went on numerous raids looking for the Confederate general and his soldiers, they never captured him. Following the war, Forrest is chiefly noted as the first “grand wizard” of the Ku Klux Klan.

In August 1864, George’s regiment left Memphis searching for Forrest. George stayed behind at Fort Pickering. The departure of the regiment was ill timed; Forrest circled around the Union troops and raided Memphis. Forrest’s soldiers sacked the headquarters of Union General Cadwallader Washburn, an ineffectual bungler who fled out a back door in his nightclothes, running down a street to reach the safety of Fort Pickering. Though the Confederates soon left the city, they considered their plucky raid a triumph because of the embarrassment brought to General Washburn.

For George Richardson, there was nothing plucky at all about the raid. George stayed in the fort, immersed in the blood of the dying. He ministered to both Union and Confederate wounded as they were brought into the fort’s field hospital. “I received messages from the dying which they sent to their friends in the South and in the North.”

In April 2004, I traveled to Memphis hoping to walk the ground of Fort Pickering, or what is left of it. A few mounds of dirt are all that remain of the fort’s ramparts near a railroad bridge in an industrial part of town along the Mississippi River. To find it, I needed the assistance of the Memphis Public Library, which directed me to the site of the fort using an old map of the city.

Where Washburn’s headquarters once stood is now a minor league baseball stadium for the Memphis Redbirds. A marker near an entrance to the stadium takes gleeful note of Washburn’s flight from Forrest’s raiders. Indeed, civic Memphis has a decidedly Confederate tilt to this day, with many historical markers and monuments to the Confederate Army, including Nathan Bedford Forrest Park with a heroic statue commemorating the father of the KKK. A pastor friend of mine in Memphis, wincing as we drove by, called it “War Criminal Park.” Memphis has no historical markers for Fort Pickering or monuments to the black Union soldiers who served and died for their country and freedom, and died at the hands of Forrest and his rebels.

If there are Ground Zeros in American racial history, Fort Pickering is one of them. Two centuries of crucial moments in American racial history intersect at Fort Pickering. Old maps show that after the Civil War, a black neighborhood in Memphis took its name from the fort. The neighborhood was subjected to a vigilante riot from whites in 1866. A dozen years later, a yellow fever epidemic was a cataclysm like Hurricane Katrina. The white citizens fled Memphis; the black citizens had no way to escape and died. A monument to the yellow fever epidemic and a group of white Catholic, Episcopal and Anglican nuns who died tending to them is now a few short yards away from the grounds of Fort Pickering. The nuns are commemorated by a feast day on September 9 by the Anglican and Episcopal churches, known collectively on the calendar of saints as “The Martyrs of Memphis.”

Almost a century later nearby another martyr was killed. The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered in a motel not far from Fort Pickering. The motel is now the site of the National Civil Rights Museum. During my visit to Memphis, I visited the motel and museum; I could not help but reflect that that George Richardson must have walked past that spot many times during the Civil War.

The site of the Civil Rights Museum is about halfway between the Union fort and Washburn’s headquarters. Perhaps Washburn even dashed past there on his way to safety on the night of Forrest’s raid. A few blocks further east is Beale Street, where twentieth-century African Americans created a richly distinctive style of Memphis blues, and Elvis Presley became a cultural icon by copying them.

During the Civil War, black soldiers brought with them their wives and children. Their families camped near Fort Pickering, and in January 1865, General Washburn decided to move the women and children to a refugee camp on President’s Island in the middle of the Mississippi River south of Memphis.

Washburn imperiously ruled that the soldiers weren’t legally married because plantation slave marriages had no force of law. The alarmed black soldiers came pleading to George for help. George came up with an ingenious plan; if marriage was the issue, he decided to perform “legal” weddings for the soldiers.

George convinced friendly white officers to delay enforcing Washburn’s order for a week. Then George obtained passes for the soldiers to bring their wives into the fort and to be lawfully married. “The tide began to roll in Jan. 24th [1865] and for a week I had plenty to do,” he wrote.

George carefully recorded in his notebook each of the weddings; there were 16 on Jan. 26; and 23 more the next day. He wrote down names like Absalom Fields and Agnes Fields, and some of the white officers served as witnesses, including a Lt. Smith and a Capt. Washburn.

“They came in squads, and finally I was obliged to marry them in squads.”

When George was finished, his soldiers were legally married in the eyes of the Union Army, and General Washburn apparently had no other recourse that to grant a reprieve from being rounded up into a refugee camp. A one-armed Methodist chaplain had outsmarted him.

During my visit to Memphis, I walked the ground of President’s Island where the refugees would have been sent but for George's actions. The island is now is a large sandbar in the middle of the Mississippi River, and is a site for gravel quarries and tank farms. President’s Island is where modern Memphis consigns its necessary-but-toxic industries, accessible only across a narrow land bridge. It is easy to see why the black soldiers were so alarmed at the prospect of their families being exiled to the sandbar. The marshy island was infested with mosquitoes, and in fact, Memphis was decimated by a yellow fever epidemic a decade after the war. Most of the victims were black.

George remained with his black regiment for the duration of the Civil War, leaving the fort with the regiment as it attempted to track down Forrest on a raid into Mississippi. Camping in the field, on the eve of battle, George wrote that he could hear the black soldiers praying:

“There was another colored Regt camped near ours and I could hear the voice of prayer from them as well as from our own men. The voice of prayer from so many at the same time, made the place seem wonderfully sacred. I said ‘Surely God is in this place.’ This circumstance impressed me deeply.”

In Spring 2007, I traveled to Mississippi to attempt finding where George and his soldiers may have camped on the night before that raid. I stayed at an Episcopal Church retreat center that happens to be on the ground where the 3rd U.S. Colored Cavalry Regiment camped before a raid on a nearby Confederate-held bridge. The retreat center has on display artifacts unearthed from the encampment, including canteens and bullets. The spot could well have been where George and his troops camped, though there is no record of his unit being in the vicinity. Perhaps the 3rd U.S. Colored Cavalry was the other “Regt” he had referred to in his journal. The 3rd Colored was attached to the Army of the Tennessee and records show it was posted in Memphis and made raids deep into the Mississippi Valley throughout 1864. That there is no record of a detachment of George’s regiment accompanying the 3rd is not unusual; units were often mixed together, particularly for raids.

I went to Mississippi wondering if I could still hear the echo of so many men at prayer so long ago, knowing that this hallowed ground was where many men spent the last night of their lives on earth. A dirt road leads from the peaceful Duncan Gray Retreat Center to a nearby bluff where the African American Union soldiers camped. The site of the encampment is in a meadow full of wet thick grass, thistles and wildflowers. I left the road, and crossed the encampment ground. Walking was difficult and my shoes and socks became soaked.

I found an old rotting log to sit on, and I stayed a good long while. I could picture the men riding out of the woods to make their camp on the high ground of the clearing. The bridge that was their target was a few miles beyond. I wondered if my ancestor was with them, and I wondered if the gunfire the next day could be heard from this place. I listened to a Charles Wesley Methodist hymn on my iPod: “Come let us anew our journey pursue…Our life as a dream, our time as stream… for the arrow is flown and the moments are gone.” Perhaps George sang that Methodist hymn, or another, on that night with his troops.

When I walked back I found a piece of rusting iron plate half-buried in the road. It was probably from an old farm wagon. Or maybe it had been dropped by the men who camped there so long ago. I turned it over, held it, then left it in the road.

The next day, I walked with a friend a couple of miles to an old African American cemetery in a Baptist churchyard. Most of the tombstones were from the twentieth--century, but on the edge of the woods, half covered with vines, were the graves of people born in the 1850s. They had been born into slavery, and perhaps some of them as children or teenagers heard the gunfire from the raid on the Confederate bridge. I wondered what they would have felt as they saw Union soldiers – black Union soldiers – charging out of the woods? What stories did they tell their children of that day?

As we walked through the cemetery, an elderly African American man got out of his pickup truck and put flowers on his mother’s grave – it was Mother’s Day. He used a golf club to brush the grass ahead of him as he walked, sweeping it for snakes. I asked him how many types of snakes in the area might be poisonous.

“All of them,” he replied.

“My convictions…came back to me”

The Civil War ended in April 1865 and George was at his post in Memphis when the news came by telegraph of both the fall of Richmond and the surrender a few days later of General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House. George recorded the event in his journal, and the tragedy that followed:

“About 4 o’clock in the afternoon of April 4th the news of the surrender of Lee and the fall of Richmond reached Memphis. The city was illuminated and guns were fired and there was wild joy among all the Union men. It meant that the hardships of the field were about at an end. It meant that the soldiers, after an honorable discharge, could return to their families, and to their peaceful occupations. It meant that the thousands of prisoners who had languished in military prisons or in prison pens would at once be liberated, and breathe the air of freedom once more. It meant that the principles for which our nation had contended for four years had at last triumphed, and that America would henceforth be “the land of the free and the home of the brave”. It meant that the four and a half million of men, women and children of African dissent [sic] would have a chance to become intelligent American citizens; and this class were very demonstrative in their joy.”

At the news of President Lincoln’s death, a group of black soldiers asked George to come speak at Collins Chapel, a black church in Memphis. He hastily went with them. “At the church I found a large congregation that had been moved by one impulse to go to the house of God in this the greatest calamity of their lives. They had just begun to taste the sweets of freedom, and now it was dashed from their lips forever.”

George may have preached the sermon of his life, telling the ex-slaves that their freedom could not be taken from them so easily, and that God had “surely seen their affliction.” He compared Lincoln to Moses, saying neither made it to the Promised Land. “I saw their faces brighten as I talked with them in this strain about forty minutes.”

In the years to come, Collins Chapel became known as the “mother church” of the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, which later changed its name to Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the largest predominantly black denominations in the United States. Collins Chapel today is a thriving church, and I have wondered if some of the congregants are descendants of the soldiers and their wives who were married by George Richardson at Fort Pickering.

George stayed in Tennessee another ten months, and he bore witness to one of the great tragedies of the war’s aftermath. In August 1865, the steamboat Sultana made its way up the Mississippi River. The steamboat was overloaded with former Union prisoners of war, many of them very sick after captivity in Confederate prison camps including the notorious Andersonville. A few miles north of Memphis, the steamboat blew up, and 1,700 lives perished, the worst maritime accident in history until the sinking of the Titanic in the twentieth century.

“At daylight the dead bodies could be seen drifting past the fort like flood wood,” George wrote. A lieutenant with a squad was dispatched to gather up bodies, and an unnamed woman in town prepared the remains. “I gave them a Christian burial.”

George was discharged from the Grand Army of the Republic in January 1866. Before departing for home, he and other Army chaplains took a tour by horseback of Tennessee, Mississippi and Arkansas, and his journal records much of what he saw in the war-torn South. They cut short their tour when they heard rumors that the former rebels might ambush them.

As George prepared to go home to Minnesota, a contingent of his former soldiers asked him to stay in Memphis and start a church. All of the men were ex-slaves, and none was willing to go back to the Deep South; they wanted to stay in Memphis and build a community. Calling themselves the “Fort Pillow Boys,” they asked George to be their pastor.

“It was hard to disappoint these men who had clung to me so confidingly. But I had to tell the committee I have been away from my family most of two years, and I will not under any circumstances be separated from them any longer.”

His other reason, which he confided to his journal but not to them, is he did not think it safe for his family to live in Tennessee where he had heard reports of marauding bands of Southern whites were killing northerners and ex-slaves with impunity. The war was over but the old order was still very much alive.

George returned home to Red Wing and threw himself back into being a Minnesota circuit-riding Methodist preacher. He worked himself to the point of exhaustion and beyond. He became physically ill and short-tempered at the petty conflicts of congregational life. Within four years of his return to his old life and at age 47, he was spent.

“I was completely broken down, and I should have given up the charge. But I was determined to fill out the year if possible. Every sermon I preached during the balance of the year caused severe pain in my right lung. As the next conference drew near I felt compelled to retire from the work.”

If he had regrets about not staying in Memphis with his former soldiers, he did not record it in his journal. If he heard anything about the white vigilante violence in Memphis then erupting, George did not record it. Instead, he prepared to give up ministry altogether.

“This was a sad experience. I was still in the prime of life, so far as years were concerned – only 47 years old. It was very hard to get grace enough to submit gracefully to the inevitable.”

George took a small pension and retired to his farm in Minnesota. He believed his life’s work finished. Yet, George was just past the midpoint of his life. He would live another 40 years – and his greatest accomplishments were just over the horizon.

In 1875, while brooding on his front porch in Red Wing and feeling completely useless, George’s eldest son, Owen, suggested that the two of them go to the warmer climate of Texas where George might recover his health. If George hesitated about moving, he never said so in his journal.

“I found that my wife and boys had talked the matter over before Owen spoke to me about it. I had wished to have the way open for something like this, and the bare possibility that it could be realized cured me of the blues at once.”

Owen went ahead and found a place to stay in Dallas. George arrived, and he rested for a few weeks. His health and spirit began to recover. “Hope that my work was not done began to revive. My feeling of despondency began to subside. I cannot describe the joy I felt at the prospect that my days and usefulness might be prolonged and that God might add to my life as many years as he did to Hezekiah.”

He attended the annual Methodist conference in Austin, and met Methodist Bishop Andrews, who concluded that George was not strong enough to endure circuit-riding work, especially in Texas – at least not yet. “When I reported to the conference at Austin I was willing to take work among the white people or colored people wherever I was needed most.”

Most crucially, George met three black Texas preachers, Charles Madison, Mack Henson, and Jeremiah Webster. Their meeting would have far-reaching significance to this day. The three preachers were among the few black preachers who could read and write, and they impressed upon George the enormous need to help their community become literate.

George began forging a remarkable partnership in particular with Pastor Webster by agreeing to help him start a school for blacks at St. Paul’s Methodist Church in Dallas. Pastor Webster’s passion – and courage – is evident from the pages of George's journal; Jeremiah Webster is certainly one of those unsung American heroes whose name is nearly lost to history but whose courage and endurance made an enormous difference in changing lives and inspiring others.

For George Richardson, meeting Webster was nothing less than the rediscovery of his own calling.

“My convictions that I had when I left Memphis in 1866 all came back to me. Here among these colored preachers and people is my field of labor.” Like many other whites who had worked to end slavery, George discovered that the work of emancipation was not finished but had only begun. Education was a keystone if the former slaves were to break the bonds of servitude and escape the Southern rural sharecropping system. They stood very little chance of breaking the shackles of the sharecropping system without a few brave souls like Jeremiah Webster – and George and Owen Richardson joined them.

Webster and the Richardsons opened their “colored” school at St. Paul’s Church in February 1876 with six pupils, or “scholars” as George endearingly called them. The school was in a simple wooden building that doubled as a church on Sunday. The unfinished building was drafty and cold. They charged $1 a month for tuition.

“St. Paul’s Church was in the Negro quarters of Dallas. They were all poor and depended on their daily labor for their existence. If there were two or three in one family that attended school it meant quite a sacrifice to pay 25cts a week for each.”

Somehow they came up with the money.

In June 2004, Lori and I visited friends in Dallas. During our stay, we went to the Dallas Art Museum for the opening of an art exhibit of the works of Romare Bearden, a leading African American artist of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s-30s, and as it happens, was born the year George died (1911). The Dallas Art Museum is located across the street from St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, which is now a prosperous African American church built of brick and stone. Romare Bearden used a variety of media – paint, collage, sculpture – to portray the perspective of being black in America, and he explored themes from the biblical, to rural Southern life among poor blacks, to cool jazz clubs in Harlem. I could not help but feel the exhibit was a fitting tribute to the school that had once stood nearby even if only a handful of contemporary people were aware of the school’s existence so long ago.

On a Saturday morning in April 1876, the Richardsons awoke to find the church – and the school torched by the “Kuklucks” as George disparagingly called the KKK.

“It was a pitiful sight to see the despair written on the face of that faithful colored pastor and the members of his flock – men – women and children, as they stood around the smoking brands,” George wrote. “Our scholars stood about us crying because they could not go to school any more. …We assured them that we would not leave them.”

By the next day, George and several black pastors rallied enough labor and resources to rebuild the church school – and they pointedly worked fast as a sign of their determined defiance against the KKK.

“We pressed into service every colored man that could use a saw or drive a nail. That was a busy afternoon. The sound of hammers did not cease till 9 o’clock, then we carried the seats we had saved from the fire, and our building was ready for dedication.

“Then we sang the Doxology in which the great crowd of men and women joined with a will. The notes of praise rang out all over Freedman Town, and the weeping of the morning was turned into joy in the evening.”

George describes a photograph that was taken of the Richardsons and their scholars standing in front of the rebuilt school. Pastor Webster is in the photo holding open a Bible. George wrote he would some day illustrate his journal with the photo, but I have not been able to find it.

In June 1876, with the school rebuilt, George realized he needed help and money – and he yearned to have Caroline to join him in Dallas. George headed back to Minnesota to talk with Caroline. “She could not tell whether she would be willing to make her home in the South till she had tried it.” It would take another year to bring Caroline to Texas.

George returned to Austin in August 1876 with enough money to build another room onto the school; in November it was officially designated as the Methodist Conference School and called “Andrews Normal College,” named after the local Methodist bishop.

Other forces, however, far more insidious than the KKK’s torches, threatened the school. In March 1877, Pastor Webster fell ill and died, probably from an influenza outbreak. The work at the church fell apart while the school continued to grow with 120 students. George hired more teachers to handle the load and that strained the finances of the school to the breaking point. The school received no public funds, not because it was connected to a church – white church schools did receive public funds – but because the school was educating blacks. Promises of funds from the Methodist Freedmen Aid Society in the North never came to fruition, and George and Owen never got over that slight for the rest of their lives.

Adding to the chaos, the Methodist Church in Texas voted to split itself into segregated black and white conferences. Some of the black pastors, particularly Webster shortly before his death, argued that the split would result in all of the Methodists’ resources going to the white churches, with little left for the blacks. Sadly, Webster’s prediction turned out to be true.

In the aftermath of the decision to split the church into separate black and white conferences, George, who was still officially a member of the Minnesota Methodist Conference, agreed to join the West Texas conference – the black conference. George wrote in his journal that if the black conference was to have any chance at all of survival, it needed a few dedicated white pastors who could raise funds in the North. If he ever hesitated he never showed it in his writing.

In September 1877, Caroline and their daughter, Emma, arrived in Dallas, and they immediately plunged into work at the school. George opened a second school for blacks at a Baptist church, sort of an extension operation. Meanwhile, the new black Methodist conference had need of experienced circuit riders. While the black preachers were full of spirit, few had even the most rudimentary education. Many could not read or write; what they knew of the Bible they had heard only from other preachers, not from actually reading the Bible. George was prevailed upon to become the presiding elder in a black circuit to oversee the organizing of black Methodist churches. Owen nicknamed his father “The Traveling School” because George filled his “hack” with books for his preachers. Collecting enough money to pay for the books was a constant concern.

George made his headquarters in Austin, leaving Caroline, Owen and Emma to run the school further north in Dallas. By the end of the school year it was apparent the school needed to move to Austin. In October 1878, the school reopened in Austin, where the Richardsons relocated. The official reason for the move, as stated in George's journal, was that there were more blacks in southern Texas than in northern Texas, and that Austin, as the state capital, was more visible and more centrally located than Dallas. George’s work was increasingly focused in small black settlements south of Austin, so the move made some sense.

All of those reasons for moving the school were certainly valid enough. But there was another insurmountable reason for the move that George never mentioned in his journal, but which is mentioned in his son’s journal. Owen wrote that at the end of the school year, the black students had upstaged the white students in a citywide exhibition of learning skills. Mortified Dallas officials retaliated by imposing a test on all the teachers in Dallas, and Owen suggests that the test was really aimed at closing the “colored schools” because only one black teacher passed the test. The Dallas public schools succeeded where the Ku Klux Klan had failed by forcing closure of the black school.

The school reopened in Austin, where it turned out there was less need for black schools than in Dallas. George wrote that the Austin public schools were educating blacks such that the Methodist black school had a difficult time initially attracting students.

While the school made the move to Austin, George journeyed to Mt. Pleasant, Texas, a black colony east of Dallas where his friend and collaborator, Jeremiah Webster, was buried. The East Texas region is heavily wooded and swampy, and I covered that territory during my research for the Willie Brown book. East Texas resembles in appearance and social structure the Deep South more than it does the rest of Texas, with a thickly imbedded culture of white superiority and black servitude. From the tone of George’s journal, it was almost as if George was apologizing to his friend for moving the school, but assuring him the work would go forward. Once again, George reclaimed his calling.

“It seemed to me a very sacred spot,” George wrote. “All the intensity with which he labored to build up our school came back to me while I stood at his grave.” He remembered how Webster seemed “crushed” when the school burned, and his “intense delight” when “we decided to rebuild in the very face of our secret foes.” And George remembered how Webster worked to raise money. “I think now, though I did not realize it at the time, that he overworked that year, and that hastened his death.”

In Austin, the school began growing and became a family operation: Caroline, Owen and his wife, and his wife’s sister taught classes. Another brother, Mercein, who took over teaching the primary grades, joined Emma, now 16. The entire extended family moved into a house rented from the family of The Rev. Charles Gillette, an Episcopal priest who founded St. David’s Episcopal Church in Austin.

Before the war, Gillette was an anti-slavery and Union sympathizer; when the Civil War broke out, his congregation prevailed upon him to flee for his life. He escaped, but fell ill and died. His house stood empty and his family would not allow it occupied; many in Austin thought it was haunted by Gillette’s ghost. George rented the house for $15 month, figuring that Fr. Gillette’s ghost would approve using as housing for a black school. “We dignified it with the name Gillette Mansion.”

St. David’s Episcopal Church today is a thriving congregation in the heart of Austin. I have worshipped there on trips to Austin. I corresponded with the archivist at St. David’s to see if we could locate “Gillette Mansion.” Alas, the house was torn down years ago to make way for state office buildings.

Rather than buying a house for his large family, George purchased land for the school on the black side of town – six lots for $1,350, an amount he was hard pressed to pay. As it turns out, the lots were never used for the school, and the property is now Zaragosa Park in the predominantly African American neighborhood of East Austin.

The school itself was located in Wesley Church, located on a hill at Ninth and Neches streets near the Texas state Capitol building. The site is now a Southern Baptist Church, and how that came to pass is one of the uglier stories of modern Texas history. In the early twentieth century, as racial segregation became rigidly institutional, the city of Austin forced all black businesses – including black churches – to relocate to the east side of town upon threat of having their utilities cut off. Wesley Church moved, giving up what became prime real estate in downtown Austin. We visited the “new” Wesley Church on our trip. The cornerstone from the old church – the church of George's era – is in the garden.

“My deadly enemies…compass about”

As the school grew, so did the Richardson’s’ expenses. In 1880, George went to the Methodist national General Conference in Cincinnati to plead for funds and promote the colored school. He stayed in a boarding house for weeks, and made contact with the leading luminaries of Methodism and those working to establish schools for the ex-slaves. George left Caroline behind in Austin to run the school, and her strain showed in a letter she wrote on May 16, 1880, chiding him for forgetting their wedding anniversary:

My Dear Husband,

Have you remembered that this is the anniversary of our marriage, or have you been so busy listening to the great celebrities that you have forgotten about it?

Caroline continued in her letter to catch him up on the doings in the school and churches. “The Pastor at Fort Worth has got into trouble and resigned. So Fort Worth is without a pastor but Sister Underhill and another sister are having revival meetings attended with great success.”

The pressure of finances pushed George back on the road with his horse and hack. George rode his circuit to the black churches to the south and east of Austin, and he returned with monetary collections to keep the school going. During our trip, we drove the route of his circuit, stopping in several of the towns that were in George's charge. To the south of Austin is Lockhart, which many Texans believe is the barbecue capital of the world. The town retains an early twentieth century rural charm. We stopped at Kreuz Market, arguably the best barbeque joint in town, and then Smitty’s Market, housed in the original Kreuz building.

We continued south on the highway, roughly parallel to the road George would have traveled, to the town of Luling, where the annual “Watermelon Thump” was underway, something like a county fair and summer harvest festival rolled into one. A sign at a local motel said “Welcome Thumpers.” The First Methodist Church, in a 1960s vintage building, is located near the center of town, while newer churches are located further out. We stopped for more barbecue. The main street of Luling is along an east-west railroad spur that George occasionally used in his travels when he was not using “horse and hack.” We turned east onto Interstate 10.

Flatonia was our next stop, a town that has prided itself on maintaining its nineteenth century charm and buildings. We stopped in the city museum and inquired if they knew where the “colored” Methodist church might be. Sure enough, they were able to direct us. We found the church, though the original building is gone, replaced by a small modern structure. We also found the stately white Methodist church, built in the 1880s. We cruised around Flatonia and found more buildings from the 1880s, including the newspaper and an old hotel.

Eventually we came to Alleyton, on the eastern boundary of George's circuit. Of all the places we visited, Alleyton is probably the least changed from George's time. It is a tiny black shantytown with gravel roads and small houses. There are two small churches, both Baptist, in the center of Alleyton. Electrical lines and automobiles were all that distinguished it as a modern town. An historical marker nearby marks Alleyton’s importance as a supply and munitions depot for the Confederate army.

We saw few people – most were indoors because of thunderstorms that within a few hours flooded low areas in that part of Texas. We soon found our way back to the Interstate. I wondered what stories there were to tell in Alleyton, and I would bet that some of the residents are descendents of those to whom George ministered.

Alleyton is a few miles north of one of the most frightening episodes of George's life. In October 1883, as George was preaching in Hallettsville, a larger town near Alleyton, word came to him that the white residents of Boxville (renamed Speaks in the twentieth century) had taken up arms because of a rumored “nigger rising.” A white man had murdered a black man and his crime had gone unpunished; the whites were fearful that the blacks would seek revenge. The rumor was that the whites blamed the Methodist circuit preacher – George Richardson – for stirring up the blacks, though he hadn’t been there in months.

There was no uprising – blacks were fearful of what the hysterical whites might do. Meanwhile, George was warned that a white posse was searching for him so “that I ought to be put out of the way.”

George took the warning seriously, and discovering that his way back to Austin was probably blocked, he hid along the Colorado River somewhere south of Alleyton – he doesn’t say where in his journal. In our travels, we explored the Colorado River near Alleyton, near where he must have hid. We looked for possible hideouts, and there are many along the river. It is a wide, sandy, shallow stream that meanders through thickly wooded flatlands. A person could easily slip into the woods and would be invisible only ten feet from the road or the riverbank.

As George hid, a black postal courier brought him messages. George, in turn, wrote notes to his family to let them know he was safe. Among the most touching is a letter he penned to Caroline, which he records verbatim in his journal:

“I had a good breakfast this morning – sat down on the ground to eat with my heart full of thankfulness, and thanked the Lord not only for the comforts, but the luxuries of life – potatoes and bacon from Kansas – Java coffee – Cuban sugar – Illinois bread – New York cheese – Texas grapes and Michigan apples – Surely thou preparest a table before me in the presence of my enemies – my cup runneth over. After eating I got up into the hack and read the 23d Psalm. Just as I had finished that, a little breath of wind turned the leaves of my Bible, and opened to the 17th Psalm, which I read through very carefully – and felt great comfort while reading, and great satisfaction in committing my ways to the Lord in prayer.”

I have read the 17th psalm many times, and each time I read it, I think of George Richardson hiding in the woods along a riverbank in Texas, far from friends and family but sure in his faith and certain in the goodness of his work. In the King James Version of the Bible, which George surely was reading, the psalmist writes about how his enemies surround, or “compass” about him, but God protects him:

"Keep me as the apple of the eye, hide me under the shadow of thy wings.

"From the wicked that oppress me, from my deadly enemies who compass me about."

Finally, the white hysteria abated and George made his way back to Austin, giving Boxville a wide berth.

George was not the only family member out on the road to support the school. Caroline increasingly traveled to small hamlets to teach African American women basic homemaking skills. George quotes from one of her reports, giving a glimpse of how hard she worked. Caroline recorded that she traveled 138 miles by hack, 530 miles by railway; talked with 23 congregations and organized two women’s auxiliaries. She distributed $20 worth of mission goods, established a small mission school with 15 pupils until “summarily closed by scarlet fever.” She collected contributions for the year of $26 for the work of the church, with $7 sent to Methodist headquarters in Cincinnati. Her traveling expenses for the year were $20.45, and she collected donations toward her expenses of $7.05.

Though they were able to meet their expenses, the Richardsons were increasingly frustrated that promises of financial support were unfulfilled from the Freedmen’s Aid Society of the Methodist Church. Finally, Dr. Richard S. Rust, the secretary of the society, came to Austin (Rust College in Holly Springs, Miss., is named for him, and is on a site George located for the school during his tour of the war-torn South after the Civil War).

George’s trip to Cincinnati in 1880 was about to pay off.

Rust brought welcome news of a benefactor – Samuel Huston, a white farmer from Marengo, Iowa, who was willing to pledge $10,000 toward the black school in Austin. Unfortunately, Huston died, and it took another decade before the school could secure the funds from his estate. The college was eventually named for Samuel Huston about whom little else is known.

Rust pronounced as inadequate the six lots that George purchased and set about finding larger site. Samuel Huston College was relocated from Wesley Church to a site at the foot of low-lying hills to the east of what is now Interstate 35, a few blocks from the Texas state Capitol building. On a nearby hill, another school, Tillotson Collegiate and Normal Institute, was established by the Congregational Church for training African American teachers. The two colleges, serving similar constituencies, were constantly strapped for cash through much of their existence. In 1952, the trustees of both schools voted to merge into Huston-Tillotson College, and located the new school on the higher hill occupied by Tillotson.

All that remains today at the site of Samuel Huston College is the foundation to one of the old buildings on a vacant lot. A windowless state office building occupies most of what was Huston College. Off to the corner in a parking lot is a Texas state historical marker noting “The Rev. George W. Richardson founded a college in Dallas for the education of African American youth…”

Huston-Tillotson University today is a thriving center for higher education with about 600 students, predominantly African American but with an increasing diversity of ethnicities and nationalities. The campus is compact; most of the buildings have a no-frills look to them. It is not a pretty campus but it has a few handsome buildings; people have pledged their dimes and nothing looks wasted or ornamental. Lori and I first visited the campus in June 2004 and we were introduced to the current president, Dr. Larry L. Earvin, and then we met with a group of pastors who are on a college advisory committee. I told them the story of their founder, George Richardson, about whom they knew little.

Dr. Earvin then took us across campus to a reception in our honor hosted for us by college trustees, faculty and alumni. On a table was a cake decorated with “Welcome Back Jim.” Having never been there before in my life, I was most humbled at this undeserved attention, and I think the cake probably should have been decorated with “Welcome Back George.”

As I talked with people, and later toured the campus, I was again asked to tell the story of George Richardson and his family, and more than a few people noted my facial resemblance to George Richardson. All told me their stories and the proud history of Huston-Tillotson University: Jackie Robinson coached basketball there before he broke into Major League baseball. John Mason Brewer, a notable scholar of African American folklore, taught there. Alumni include The Rev. Cecil Williams, the dynamic pastor of Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco.

As I walked around campus, many people shook my hand; one woman said “Whoa, roots standing in front of me.” The track and field coach stood up from behind his desk when he was told I was the great great grandson of George, and then he vigorously shook my hand. He gave me a tour of the athletic department, showing me pictures of Olympic athletes from the college, and he again told me the story of Jackie Robinson. Huston-Tillotson is a place where the past matters very much. For many at Huston-Tillotson, connecting with the past gives legitimacy and moral authority to the present – and points to the future.

With all of the attention, finally I said to someone, “I haven’t done anything. I’m just carrying the name.”

“You have done something,” one my new friends replied. “You are carrying the torch inside you of your great-great-grandfather.”

As I walked around the campus, it was as if people were saying, “Tell your great-great grandfather we are still here, we have kept the faith, and we are doing good work.”

A year later, I was invited back to give the invocation at commencement. I have never been so proud to walk in a graduation procession as that day. Just before we reached the stage, the graduates stopped, turned and formed a double column to shake hands with the faculty. As I walked to the stage with the faculty, I, too, shook the hand of every graduate that day. And then I stood to pray:

"We give thanks for the courage of our ancestors, for they feared no evil and walked through the valleys of ignorance and hatred. We give thanks for George Richardson and Jeremiah Webster, and for all of those who helped found this school, for they showed for all generations their vision of education as a cornerstone to freedom and justice. May we always be worthy of their example."

“A hero among us…”

In 1885 Caroline fainted and fell ill for several weeks. Although she recovered, it was the first inkling that her health was failing. But she pushed onward. George and Caroline by then had become active in the campaign to ban liquor from Texas. The Temperance Movement may seem almost quaint in our age of heroin and methamphetamine labs, but in the nineteenth century, homemade whisky was every bit the scourge of the African American community as drugs are today. Caroline embarked on a temperance lecture tour among African Americans in North Texas, beginning in Fort Worth. Her lectures were well attended and well received but she was exhausted.

“Her success,” George wrote, “had stimulated her beyond her strength. She did not know how weary she was, and did not give herself the proper time to rest, but immediately took her place in the school.”

Caroline was stricken with what Texans called La Grippe: influenza in October 1887. She rested and seemed better, but then had another fainting spell. A doctor came and stayed with her, and George brought in one of the women from the school to stay the night with Caroline. George went to bed at 10 p.m.

At 2 a.m. he was awakened. Caroline was dead.

“It was all so sudden! She had not entertained the thought that the end was near, at least she had not said so… We had no opportunity to say goodbye. What I would not have given for one word of parting; for one backward look when she was crossing that mysterious Border Land.”

George descended into what can only be described as a deep depression from which he never fully recovered for the rest of his life. Although he would remarry, and would outlive his second wife, his writing reflects his melancholy from Caroline’s death and it dogged him the rest of his life.

Her funeral was extraordinary by the measure of any age. Her service was held at a white Methodist church in Austin, and for the first time in anyone’s memory – and probably for the last – blacks and whites shared the pews at her funeral. To not do so would have been an insult to Caroline.

“My wife had said me only a short time before, that if she should die in Austin, she wanted the colored people for whom she had labored for eight years to have an opportunity to be at her funeral,” George wrote.

Pastor McIntire, the white pastor of Central Methodist Episcopal Church, agreed to include the blacks. He asked Pastor Mack Henson, the pastor of black Wesley Church, to invite his congregation and invited Henson to sit on the platform and take part in the service. His presence was more than fitting: Pastor Henson was there with the Richardsons at the founding of the school in Dallas.

The church was packed; both black and white pastors spoke. Pastor Henson, George recalled, “moved the audience to tears when he spoke of the sacrifice Mrs. Richardson had made in giving her time, without compensation, to improve their homes and their habits, and at last to give her life for his people.”

George initially proposed burying Caroline in Austin. But one of his sons, David, my great-grandfather, asked to have his mother returned to Minnesota where he still lived. George agreed, and he accompanied her casket by rail to Red Wing. Owen joined the train in Chicago. After the burial, George spent a month in Minnesota, and then returned to Austin, but his heart was no longer there or in his work. This time, he stayed broken.

“When I came to look round over the country where my wife had traveled with, the sense of loneliness seemed to crush me. I seemed powerless to take up the burden again.”

George resigned from the black Austin Methodist conference, leaving the school behind. His life was far from over, but he felt he could not longer continue in Austin. Three years of self-imposed exile followed; he moved alone to Clarendon in the Texas Panhandle, a liquored-soaked frontier town, and the sprawling Matador Ranch with tens-of-thousands head of cattle. George became the chaplain to 150 cowboys on the ranch and he began building a Methodist Church in Clarendon. At age 63, he could still ride a horse with one arm, and he could still preach.

In 1889, George corresponded with a family friend, Rachel Elizabeth Silver of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and she agreed to marry him. He doesn’t say much about her other than he had previously known her from a conference school. She was a teacher and went by the name “Lily.” George brought her to Clarendon, his son Owen presided over their wedding, and the two commenced housekeeping. By 1890, they were more than ready to leave the Texas Panhandle.

George and Lily moved to California, and George started a Methodist congregation in an abandoned Episcopal Church in Mott, near Mount Shasta, about a three-hour drive north from where I lived for 25 years in Sacramento. The town of Mott burned down in the 1890s and was abandoned. There are no traces of the church, or even of the town. George soon left the California Methodist conference – there was an over-abundance of Methodist preachers trying to settle in California at the time, and George was given no support for his mission.

Ironically, the contemporary Methodist Church in Dunsmuir, the nearest town, still considers him its first pastor. A decade ago, we held a reunion of all the Richardsons in Dunsmuir to honor George’s memory.

Unwelcome in California, George and Lily moved to Oregon, but the rainy, damp weather upset her asthma. They moved further inland, to Idaho, where George took charge of remote and challenging congregations in the midst of a mountain region full of Mormons. George got back on his horse and rode a circuit. It was hard work, and there were few Methodists with whom he could stay.

“I felt there was a species of cruelty about this whole business. I wondered what I had done, or failed to do, that I should be thus thrown away. It dawned on me gradually that my hair was gray, and that I was 71 years old.” Nonetheless, he hung on in Idaho another two years. Owen joined them and ran rival meetings, and George worked as his associate pastor.

With all of their hard labor in Idaho, they had won only 14 new converts to Methodism. At the age of 73, George retired from the preaching life. The Idaho Methodist conference of 1897 passed a resolution declaring that he was “a hero among us,” though no mention was made of his ministry among the black people of Texas or his service as a chaplain in the Civil War. The lack of recognition in his lifetime for his work among African Americans was certainly indicative of the indifference – and prejudice – that permeated both Northern and Southern white society and its churches.

Nor would any such recognition come from the Texas or Minnesota Methodist conferences where he had devoted the best years of his life at great personal risk and sacrifice. Perhaps it was no coincidence that he would never live in either place again.

George and Lily decided to move to Denver, a place neither had lived. He gave no reason in his journal for choosing Denver. Getting to Colorado proved to be one last adventure for them. After 47 years of work, all he owned were a few household items and a team of two horses – and he could not find a buyer for the horses. So George and Lily gathered up all of their worldly possessions, and headed out on the trail with wagon and horses. They traveled 940 miles for 45 days, fording streams, and crossing through Yellowstone and then into Montana, before arriving in Denver just ahead of an early winter blizzard.

George Richardson lived another 14 years in Denver; he agreed to be the assistant pastor to Asbury Methodist Church until infirmity kept him housebound. His youngest grandson, 16-year-old Russell – my grandfather – came to stay with him for a summer. He met his first two great-grandchildren as infants.

Ever restless, he took several long trips by railroad, including to Los Angeles in 1904 for a Methodist national conference, and he wrote a newspaper account of it. That same year he celebrated his 80th birthday with family and friends, receiving letters from old colleagues from as far away as Africa. He endured the news of the closure of Samuel Huston College in Austin for lack of funds, but he lived to hear about the college reopening. Writing in his journal in 1906, among his last entries, he noted with satisfaction that Huston College had 400 students. He made his final entry into his journal in 1907, recording the death of Lily, his second wife.

In his last days, George's daughter, Emma, came to live with him, and penned into his journal the details of his last years. Her selfless care for her father was poignant, and her affection for him is clear in her writing. But underneath her poised words was a tragic and unspoken irony. The story has come down through our family, though this is nowhere written, that when Emma was a young woman she had a love affair with a student (or a teacher) at Samuel Huston College. She was in love with a colored man. Her parents, whatever else their forward-looking views about race may have been, they were not prepared to have their daughter engaged with a black lover, and they forced her to put an end to the affair. She never married.

Emma recorded in George’s journal his death. She said that he suffered no final illness, but “simply a fading away.” He died on Aug. 8, 1911.

“The funeral was simple,” Emma wrote. “Father had made all the arrangements some two weeks before his death.” He was laid to rest in Denver, in a grave next to Lily. His casket was draped with a silk flag of the Grand Army of the Republic, and perhaps ironically, the congregation sang the same hymn that had been sung at Robert E. Lee’s funeral: “How firm a foundation, ye saints of the Lord.”

Faith with feet

Over the years, the story of George W. Richardson and his immediate family faded into the distance of family lore. His children and their children went about their business. George’s oldest son, Owen, returned from Idaho to become the first president of Huston College, but his tenure was stormy and he did not have his father’s touch with donors and Methodist bishops.

George’s second son, David – my great grandfather – was a farmer, settling in Oregon, and was never engaged with the family project in Austin. His son, David Russell (who went by his middle name), was known as the “favorite grandson” of George Richardson, and into his hands he received George’s journal and protected it as a family treasure. Russell was something of a swashbuckler; he bragged he could do 100 pushups a day into his 80s. He was a lumberjack on the Columbia River, then an officer in the Navy in World War I. After the war, Russell joined the Merchant Marine sailing ships to China and then during Prohibition, he ran bootleg rum up the Pacific Coast from Guatemala. He met my grandmother on a voyage to Hawaii, where she grew up. They eventually married and settled in Northern California, and he worked his way up as an executive in an oil company owned by J. Paul Getty. He spent the post-war years in Japan, successfully lobbying Douglas MacArthur to rebuild Getty’s oil refineries.

Russell’s son, David – my father – was born in 1922, served as a Navy officer in the South Pacific and reporting to his father on the condition of bombed0-out oil refineries. After the war, he worked for 35 years for American Can Co. until his retirement. He had his father’s love of the sea and his ashes were scattered at the Golden Gate.

All of the Richardson men were Republicans like their ancestor who had cast his vote for Lincoln.