Willie Brown: Power, Money and Instinct

SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA--Frank Fat's is the smallest building on its block. Painted garishly pink outside, the Chinese restaurant is sandwiched between a parking garage and an old brick office building a short walk from the California State Capitol.

Inside, behind the restaurant's heavy oak door, is a long, narrow bar. Fat's was remodeled in the mid-1980s to give it a fashionably slick Art Deco look. Most of the tables are in the rear. But off to one corner is a booth with a brass plaque memorializing it as the favorite table of James "Judge" Garabaldi, who until his death in 1993, was the king of Sacramento lobbyists. He represented a most lucrative set of clients: The liquor and horse racing industries. The best dish in this Chinese restaurant is the New York strip steak. But the powerful don't come to Fat's for the food. They come for each other.

On any given night when the Legislature is in session, a blue Cadillac, its motor idling, might be parked in front of Frank Fat's. Sitting inside the car, monitoring a radio and a telephone, a state driver will be waiting for Willie Brown, the Speaker of the State Assembly, the most powerful politician in California.

It was on one such sultry night -- September 10, 1987 -- that nine representatives for four economic mortal enemies assembled in the private dining room upstairs at Franks Fat's. All of them were experienced -- and well paid -- political insiders.

The four industries represented -- insurance companies, trial lawyers, doctors and manufacturers -- were also among the biggest campaign contributors to state legislators in California. Each had spent years fighting expensive battles against each other in the Legislature and at the ballot box, with little to show for it but thinner profit margins.

As plates of potstickers, Kung Pao chicken and other delicacies were shuttled to the tables, the warring industries worked out a political truce. They were joined by Democratic state Senator Bill Lockyer, the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, and eventually, Willie Brown.

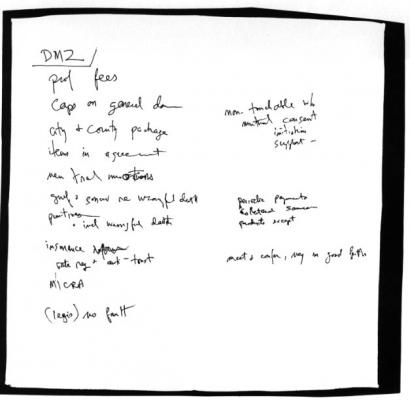

A few hours later, the group slipped out of Frank Fat's with a cloth napkin. And on the napkin was scrawled in ink the outline of a political peace pact. Each side agreed to a five-year cessation of hostilities in return for supporting the most sweeping changes in California's civil liability laws in decades.

The "napkin deal," as it came to be called, was the final touch in complex negotiations painstakingly conducted over a series of days in Willie Brown's private cloakroom in the Capitol and at Fat's restaurant. The napkin itself was penned by Senator Lockyer, a major mediator in the talks.

The legislation was rushed into print in less than 48 hours and brought to the Assembly and state Senate for immediate votes on the last night of the legislative session for the year. Fearful that the compromise among the industries would fall apart, legislative leaders allowed quick "informational" committee hearings but left no chance for changes by anyone who was not in the room that night at Frank Fat's. The legislation included a drastic restriction in product liability laws offset by fee increases for lawyers prosecuting medical malpractice cases. Doctors got promises that protections already in place against lawsuits would not be touched. Insurance companies won a reprieve from threatened regulations gaining momentum in the Legislature.

Alarmed consumer groups tried to play for time that night, pleading with weary legislators who were ready for their yearly adjournment. Democratic Assemblywoman Jackie Speier futilely asked why the Assembly could not hold the legislation over for a more careful look when it returned a few months later in January.

"I have the votes on the floor tonight," Brown replied.

Democratic Assemblyman Byron Sher, who also is a Stanford University Law School professor, jumped to his feet asking for a recess so that Democrats could at least discuss the deal among themselves in a caucus before voting.

"There will be no more caucuses tonight, Mr. Sher!" Brown snarled from his Speaker's rostrum.

And with that, the legislation was rammed through that night with lopsided votes and signed a few days later by Republican Governor George Deukmejian.

For critics of the Legislature, the napkin deal came to symbolize how narrow economic interests dominate lawmaking in California to the exclusion of public participation. "The process stinks," complained a bitter Harry Snyder, regional director for the Consumers Union. "It is outrageous to take all these special interests, find them a room in the Capitol, then say the public is not allowed."

But for Willie Brown it was one of his proudest accomplishments, and he called it the "hallmark" of the session. He had brought peace, if only for a time, to the seemingly insoluble battle over liability laws. And writing a new law on the back of a napkin in an upstairs room at Frank Fat's appealed to his sense of showmanship.

So proud were Brown and Lockyer that they reproduced the napkin on a large poster, signed it at the bottom and gave copies to their friends. Titled "Tort-Mania 1987," a copy of the poster now hangs above the pay phone at Frank Fat's restaurant.

In fact, there was really nothing unusual about the napkin deal other than the theatrical touch of writing it on a napkin (which was Lockyer's idea). The evolution of the complicated pact followed a recurring pattern throughout Willie Brown's career that displayed both his genius as a politician and the limitations of his genius.

Long identified as the protector of trial lawyers -- being one himself -- Brown was in the peculiar position of being able to force his allies into swallowing unpalatable concessions. On the offensive, doctors and insurance companies were promising a raft of ballot initiatives to trim liability laws to their own advantage unless the Legislature acted.

In a series of speeches and interviews in 1986, Brown signaled his willingness to entertain changes in California's tort system. In a speech to the California Medical Association on April 2, 1986, Brown said: "Let me assure you I don't want to be identified as a knee-jerk trial lawyer obstructionist."

Many of the details were quietly mediated by Lockyer, who began his career in the San Francisco political organization of the late-Congressman Phillip Burton -- the same organization as Brown -- but who later steered an independent course. Lockyer this year was elected by his peers as President Pro-Tem, becoming the most powerful Democrat in the California Senate.

"The public is better served when these groups are trying to mend rather than tear the fabric of society," Lockyer explained at the time.

Brown entered the negotiations when the issues became sticky, haranguing the parties when necessary or shutting them away together in his ornate cloakroom just off the Assembly floor. This time the issue was liability laws, but Brown's modus operandi is the same whether it is negotiations over the state budget, tax laws, the workers compensation system, education reform or in his earlier career as a civil rights lawyer.

Typically, Brown shuttles between warring parties, relaying ideas and proposals but also mastering the details himself searching for the weaknesses that will provide him with leverage over each participant. In the end, Brown makes everyone believe they face a fate far worse in the Legislature or at the ballot box, convincing them to knuckle under to a series of compromises.

"He tells everybody that," said John Mockler, a former Brown aide who is now a lobbyist. "You never know, right?"

Brown is master at retail politics, picking off one vote and one issue at a time. "There are very few people who are going to be able to outdo [me]," Brown said in an interview last year. Few would disagree.

But his is a genius that works best within a narrow set of players; his method requires defining the public interest as the sum total of all the players sitting around the negotiating table. Therein is Brown's weakness. He is not a good wholesale politician; he is weakest at articulating a wide vision to a wide audience. To those left out, the napkin deal had an undemocratic, almost sinister feel. "The Legislature gave away its authority over laws to some special interest groups," complained Snyder.

And, in fact, the narrowness of participation in the napkin deal brought a narrow result. Consumer groups left out vowed to get even, and did so with the successful passage a year later of Proposition 103, a tangled web of regulations and mandatory rate rollbacks imposed on insurance companies that was far more drastic than anything under consideration in the Legislature at the time of the napkin deal.

Throughout Willie Brown's tenure as Speaker -- the longest by far of any in California history -- the perception has reigned that those invited to the negotiating table are those who provide the most money to the election coffers of Brown and his friends. Editorial writers and pundits have accused him of all but posting a "for sale" sign on the Capitol dome.

Throughout Willie Brown's tenure as Speaker -- the longest by far of any in California history -- the perception has reigned that those invited to the negotiating table are those who provide the most money to the election coffers of Brown and his friends. Editorial writers and pundits have accused him of all but posting a "for sale" sign on the Capitol dome.

It is a perception Brown has tried to shake, but never quite convincingly.

The numbers speak for themselves. As the tort wars raged during the first six years he was Speaker, Brown received a total of $215,056 in campaign contributions from the California Trial Lawyers Association, an organization representing primarily plaintiffs' attorneys. In addition, the trial lawyers' organization gave a total of $652,032 to Brown's Democratic Assembly colleagues while giving only $84,050 to Republicans during the same period of time. The trial lawyers enjoyed a special relationship with Brown and were protected from the more drastic legislative proposals to trim liability laws.

In 1986, Brown told the Riverside Press-Enterprise: "If the doctors who contribute to me almost as handsomely to me as the trial lawyers, and if they have an issue that's without merit, their contributions would have no affect on how I vote or may not vote...I don't think any contributor anticipates having any influence. I think what most contributors would anticipate is having a fair hearing and having access in helping to elect people who exhibit those qualities."

Asked if he therefore excluded from participation those who give nothing, like consumer groups, Brown defensively replied: "We don't expect anybody to give money to be heard. You may."

Mockler, who has been associated with Brown since 1959 and is considered one of his closest advisers although he no longer works for him, said Brown is "very cognizant of money." But, Mockler insisted, "Willie Brown can't be bought because everybody's in there. He's not `if you give me money, I'll do something.' I've seen him in rooms where people even hint in a conversation about an issue and a fund-raiser. He stops immediately and sends them out of the room."

But critics detect a deep rooted cynicism in Brown's contribution gathering. He takes from one and all -- tobacco companies, health care organizations, bankers, oil companies, trash haulers -- anyone who will pay. For the most part, who they are and what they stand for never seem to matter.

"Whether you're on the side of Citibank or the Bank of America on interstate banking -- who cares?" said Mockler, reflecting the view many believe permeates Brown's political operation. "It's a bunch of fat white guys spending a lot of money wrestling with each other where nobody ever wins or loses. A lot of issues in the Legislature that the public and press think are `corrupt' are really simply economic interests fighting for advantage with each other... The results don't matter one way or another."

Those who know Brown best say that he does his finest work when money, politics and his deepest held beliefs converge. A few issues do matter to Brown, and among the few is education.

In recent years, Brown has been considered the chief political protector of the California Teachers' Association, one of the largest labor unions in the state with 250,000 members. In turn, the CTA has showered Brown and his allies with millions of dollars in campaign contributions and consistently provided him with armies of precinct workers during elections.

But Brown's relations with the teachers were not always so strong. Pivotal to that relationship was the hiring by the CTA in 1984 of Alice Huffman, a former legislative aide to one of Brown's closest allies, then-Assemblywoman Maxine Waters, who is now a Democratic congresswoman from Los Angeles. Huffman also doubles as the president of the Black American Political Association of California, an organization founded by Willie Brown in 1979.

In a lengthy interview, Huffman acknowledged that the CTA's relationship with Brown was initially built on a foundation of campaign money.

"I wasn't here three months before Willie Brown called up and had one of those meetings where he'd have all the lobbyists lined up," she recalled. "I went in and he said `I need `X' number of dollars from CTA and I want it by a certain time. Can you help me?' And I go, `Well, I'm kind of new but I'll call over and see what I can do.' "

When Huffman called her bosses at CTA headquarters in Burlingame, a suburb south of San Francisco, she got a quick response. " `We can get the money but it has conditions,' they told her, she said.

The condition was simple: Brown had to come pick up a check for $25,000 himself. Initially, Huffman said, Brown's staff balked at the request.

Then, she said, "Willie calls up two days before this event and he says 'Alice Huffman -- where's the money I asked you for?' And I go `You didn't get my message?'

"'What's the message?' Brown replied.

"'That you pick it up. I think I've called your office ten times and I've been told you can't come.'

"And he said `What!?'"

Brown agreed to pick up the check at CTA headquarters, she said. And he told her: " 'Don't ever take a 'no' from me unless you are talking to me personally.' "

As Huffman further tells it, Brown's relationship with the CTA was cemented solidly in the 1986 legislative elections. Huffman said she was overwhelmed with requests for campaign contributions from state lawmakers and she asked the advice of then-Assemblyman Richard Floyd, a blunt-speaking Democrat who was tight with labor unions.

"He said `You really want to do something smart?' she recalled Floyd telling her. " `Then go and talk to Willie about it. And let Willie direct you.' He said `Empower Willie.'"

She arranged a meeting with Brown, who jumped at the chance to channel the CTA's campaign contributions.

"He said `I'll educate you.' And he did. He got his staff and he told me about all the races and which ones he thought he could win and where they were putting their resources and where they weren't putting them. This was highly confidential stuff," Huffman recalled.

Since then, the CTA has been a virtual gear in Brown's election machine, although he and the union have disagreed occasionally on whom to back in Democratic primaries.

"We know our fate rises and falls with the Democrats," said Huffman.

For the CTA, the relationship bore its richest fruit in 1992. The state faced a mind-boggling $10.7 billion hole in the $57 billion state budget because of a downturn in revenues from the recession. With fully half of the state budget going to school districts, Republican Governor Pete Wilson proposed cutting $2.6 billion from schools.

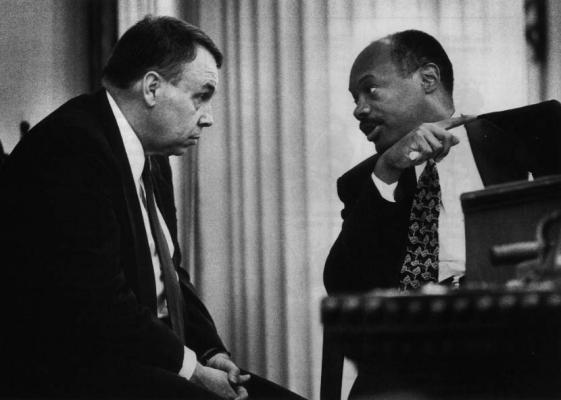

Although the Senate voted for the cuts, the Brown-led Assembly refused to pass Wilson's proposed budget. Through the heat of a scorching summer, the Assembly sat -- and Brown and Wilson faced-off with ever angrier volleys of insults. California was technically bankrupt, unable to pay its bills. The state issued vouchers -- I.O.U.s -- instead of checks, and banks refused to accept them after several weeks. The stalemate ranked as the longest and worst fiscal crisis of any state in American history.

Finally, 64 days past the July 1 constitutional deadline for passage of a budget, Wilson gave up and dropped his proposed school cuts. For Brown's supporters, it was his finest moment as Speaker.

Vindication came in November 1992. Although Wilson predicted voters would punish Democrats for the budget stalemate -- and bring about Brown's ouster as Speaker -- the Democrats increased their majority by one seat to 47 in the 80-member Assembly. Wilson's poll standings plummeted to the lowest ever recorded for a California governor.

Was it just the teachers, their money and partisan politics that motivated Brown to block Wilson's proposed education cuts? Those closest to Brown, including Huffman and Mockler, believe there was something more at work -- a convergence of politics and Brown's inner convictions. It is doubtful Brown would have blocked the state budget for as long as he did, with all the enormous political risks, for just any political patron, no matter how well staked.

"His instinct is with education as the only positive salvation," said Mockler who advises Brown principally on education issues. "I think that both politics and instinct meet there."

To Huffman, Brown was motivated as much in the summer of 1992 by something more, something deeper. To her, he was motivated by his bitter remembrance of "the gap that he had in his background" in a small, rural, racially segregated school in Mineola, Texas. His bleak school had no indoor plumbing, the books were discards from the white high school, and the children were frequently forced to miss school to pick cotton.

Quite unexpectedly, it became a day of healing for him and his hometown.

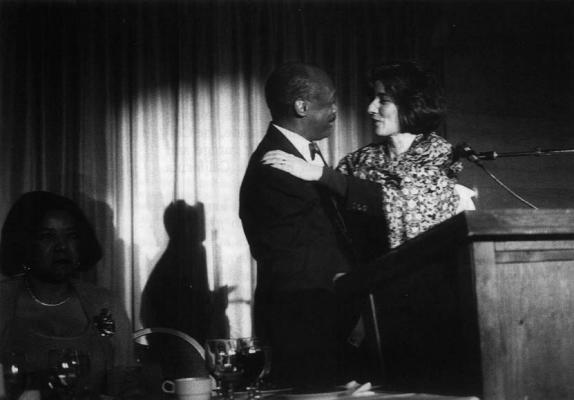

When Brown arrived in Mineola, to his astonishment, he was greeted by the mayor, the city council, the chamber of commerce, along with a judge, a Texas state legislator and about 100 townsfolk. They gave him a key to the city and surrounded him asking for his autograph.

Mineola has changed since Brown left in 1951. The town is trying to reinvent itself -- and its past -- as a tourist center with Victorian-style bed-and-breakfasts. The fact that Brown -- a black man -- was honored at all was evidence of the change. Newcomers scarcely aware of Mineola's legacy of segregation were anxious to acknowledge Brown when they heard he would be visiting. The city council declared it "Willie Brown Day."

Visibly moved, Brown told the gathering, "We were separate and distinct when we lived here. Thank you for letting this Mineola feel so good."

He soon returned to California, back to a state that did not quite love him but which remained fascinated by him, and back to a life story very much unfinished. But in Mineola on that muggy Texas night, Willie Brown was, at last, the hometown son who had made good.